Zabecki Station Master at Treblinka

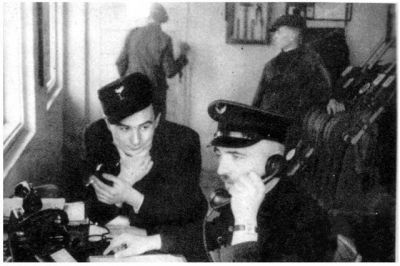

Franciszek Zabecki answers the telephone in the Treblinka Station (Robert Kuwalek)

Franciszek Zabecki was the Polish stationmaster at Treblinka village station and a member of the Polish Underground. He had been placed at Treblinka by the Underground originally to report on the movement of troops and equipment. He was thus the only trained observer to be on the spot throughout the entire existence of the Treblinka death camp.

Zabecki recalled in an interview with Gitta Sereny, in her book ‘Into that Darkness: ’

The first inkling we had that something more was being planned in Treblinka was in May 1942, when some SS men arrived with a man called Ernst Grauss who – we found out from the German railway workers – was the chief surveyor at the German District HQ. They spent the day looking around and the very next day all fit male Jews from the neighbourhood – about a hundred of them – were brought in and started work on clearing the land. At the same time they shipped in a first lot of Ukrainian guards.

Many of the Ukrainians had friends near here in the village closest to Treblinka, a hamlet of two hundred inhabitants called Wolka- Oknaglik. It’s a tiny place, no school or church – the children go to school six kilometres away in Kossov. But it was from there we began to hear rumours.

It was said that it was to be another labour camp; a camp for Jews who would work on damming the River Bug; a military installation; a staging or control area for a new secret military weapon. And finally, German railway workers said it was going to be an extermination camp. But nobody believed them – except me.

23 July 1942 – the day before we had had a telegram announcing the arrival of shuttle trains from Warsaw with ‘resettlers.’ This wire was followed by a letter –telegram giving a schedule for the daily arrival of these shuttle trains as of the following day.

At one moment two SS men came –from the camp I think – and asked “Where is the train?” They had been informed by Warsaw that it should already have arrived, but it hadn’t. Then a tender came in – the sort called a railway –taxi, with two German engineers, one was called Blechschmied, the other his assistant, Teufel. They had been sent ahead to guide the first trains along the new track, into the camp.

Franciszek Zabecki continued the harrowing scenes that accompanied this first transport of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto:

The first train to arrive on the morning of July 23 made it presence known from a long way off, not only by the rumble of wheels on the bridge over the River Bug, but by the frequent shots from the rifles and automatic weapons of the train guards.

The train was made up of sixty covered wagons, crammed with people. There were old people, young people, men, women, children and infants in quilts. The doors of the wagons were bolted, the air gaps had a grating of barbed-wire. Several SS men, with automatic weapons ready to shoot, stood on the foot-boards of the wagons on both sides of the trains and even lay on the roofs.

It was a hot day; people in the wagons were fainting. The SS guards with rolled-up sleeves looked like butchers, who after murdering their victims washed their blood-stained hands and got ready for more killing. Without a word we understood the tragedy, since ‘settling’ people coming to work would not have required such a strict guard, whereas these people were being transported like dangerous criminals.

After the transport arrived, some fiendish spirit got into the SS men; they drew their pistols, put them away, and took them out again, as if they wanted to shoot and kill straight away; they approached the wagons, silencing those who were shrieking and wailing, and again they swore and screamed.

Shouting, “Tempo, schnell” ‘At the double, quickly,’ to the German railwaymen who had come from Sokolow Podlaski, they went off to the camp, to take over their victims there ‘properly.’ On the wagons we could see chalk marks giving the number of people in the wagons, viz: 120, 150, 180 and 200 people. We worked out later that the total number of people in the train must have been about eight to ten thousand.

The ‘settlers’ were strangely huddled together in the wagons. All of them had to stand, without sufficient air and without access to toilet facilities. It was like travelling in hot ovens. The high temperature, lack of air, and the hot weather created conditions that not even healthy, young, strong organisms could stand. Moans, shouts, weeping, calls for water or for a doctor issued from the wagons. And protests: ‘How can people be treated so inhumanly? When will they let us leave the wagons, altogether?’

Through some air gaps terrified people looked out, asking hopefully; ‘How far is it to the agricultural estates where we’re going to work?’ Twenty wagons were uncoupled from the train, and a shunting engine began to push them along the spur-line into the camp. A short while later, it returned empty. This procedure was repeated twice more, until all sixty wagons had been shunted into the camp, and out again. Empty, they were returned to Warsaw for more ‘settlers.’

Zabecki decided to investigate further and travelled along a road that ran near the perimeter of the death camp:

I took a bicycle and cycled a stretch up the road and then got off, pretending that my chain had slipped, in case somebody saw me. I heard machine-guns, and I heard people screaming, praying to God and yes to the Holy Virgin. I cycled back and I wrote a message to my Home Army section chief – we used to leave our messages under the arms in the statue of the saint in the square in Kossov – I informed my chiefs that some disaster was happening in my district.

At the Treblinka village station Franciszek Zebecki witnessed a number of brutal incidents involving Jews trying to escape from the transports headed for the death camp. The first incident he recounted:

I saw a policeman catch two young Jewish boys. He did not shut them in a wagon, since he was afraid to open the door in case others escaped. I was on the platform, letting a military transport go through. I asked him to let them go. The assassin did not even budge.

He ordered the bigger boy to sit down on the ground and take the smaller one on his knee, then he shot them both with one bullet. Turning to me he said: “You’re lucky, that was the last bullet.” Round the huge stomach of the murderer there was a belt with a clasp on which I could see the inscription ‘Gott mit uns.’ God is with us.

The second incident took place after a train arriving late in the evening, was kept overnight at the Treblinka village station and the following morning the Ukrainian guards acted thus:

A Ukrainian guard promised a Jewess that he would let her and her child go if she puts a large bribe in his hand. The Jewess gave the Ukrainian the money and her four year old child through the air gap, and afterwards, with the Ukrainian’s help, she also got out of the wagon through the air gap.

The Jewess walked away from the train, holding her child by the hand; as soon as she walked down the railway embankment the Ukrainian shot her. The mother rolled down into a field, pulling the child after her. The child clutched the mother’s neck. Jews looking out of the wagons called out and yelled, and the child turned back up the embankment again and under the wagons to the other side of the train. Another Ukrainian killed the child with one blow of a rifle butt on its head.

A third incident also at the Treblinka railway station was witnessed by Zabecki:

One mother threw a small child wrapped up in a pillow from the wagon shouting: “Take it, that’s some money to look after it.” In no time an SS man ran up, unwrapped the pillow, seized the child by its feet and smashed its head against a wheel of the wagon. This took place in full view of the mother, who was howling with pain.

A fourth incident involved Willi Klinzmann, from Wuppertal. He was one of two German railwaymen who supervised the shunting of the deportation trains from the Treblinka station to the death camp.

There was an SS man from the camp in Klinzmann’s flat. A frightened, battered Jewess who had managed to get out of a wagon came into the station building. She probably thought she would be safe here. Crossing the threshold of the dark corridor close by the door of the German railwaymen’s quarters, she uttered a large groan and a sigh.

Willi rushed out into the corridor and seeing the woman he shouted: “Bis du Judin?” Are you a Jewess? The SS man rushed out after Willi. The frightened Jewess exclaimed, “Oh My God!” escaped to the waiting room next to the traffic supervisor’s office and fell down exhausted near the wall. Both the Germans grabbed the woman lying there; they wanted her to get up and go out with them. The Jewess lay motionless.

It was already late evening. As I went out to see to a military transport passing through the station, I shone my lamp on the woman lying there; I noticed that she was pregnant and in the last months of pregnancy at that. The Jewess did not react to the German’s calls, uttering groans as if in labour. Then Klinzmann and the SS man from the camp began to take turns at kicking at random and laughing.

After dispatching the train, I had to go into the office again through the waiting room, but I could not do it. In the waiting room a human being, helpless, defenceless, - a sick, pregnant woman – had been murdered. The impact from the hobnailed boots was so relentless that one of the Germans, aiming at her head, had hit too high, right into the wall.

I had to go into the office and pass close to the murderers, since the departure ofr a train to Wolka-Okraglik station had to be attended to. My entrance made the criminals stop. In their frenzy they had forgotten where they were, and somebody plucked up courage to break in and stop them in their ‘duty’ of liquidating ‘an enemy of Hitlerism.’

They reached for their pistols. Willi drunk, mumbled ‘Fahrdienstleiter’ Traffic supervisor. I closed the door behind me. The butchers renewed the kicking. The Jewess was no longer groaning. She was no longer alive.

At the beginning of the second week of August 1942, at Treblinka railway station, Franciszek Zabecki witnessed another incident. A Polish partisan, Trzcinski, from a nearby village, had reached the station after being forced to flee across the River Bug. He was on his way south, armed, in search of another partisan group, and intended to travel south on the regular train to Sokolow. At an adjoining platform were carriages waiting to be shunted on to the death camp spur. Then Zabecki recalled what happened next:

Trzcinski went up to a wagon, suddenly unfastened his coat, and gave a young Jew a grenade, asking him to throw it among the Germans. The Jew took the grenade and Trzcinski jumped into the moving passenger train and departed.

Zabecki later learned that:

The Jew threw the grenade in the death camp at a group of Ukrainians standing besides the Germans on the unloading ramp. One Ukrainian was seriously wounded. The revenge of the Germans and Ukrainians was terrible – the young men were beaten with sticks until they lost consciousness. All of them died.

Zabecki noted that from September 1942 no more passenger trains stopped at Treblinka village station, only military trains and deportation trains that were divided up and shunted into the death camp.

He also recalled that beyond the railway lines and parallel to them, ran a concrete road, beyond which was an excavation overgrown with bushes. Fugitives, seeing this thicket, often hid there before fleeing further away. But, more often than not, they died there from wounds received as they had jumped from the train: injuries from falling, or shots from the guards. The SS men knew about this, and scoured the thicket with a dog.

As Zabecki’s own allotment was not far away from the thicket he saw quite a few tragedies, as a train of deportees stood in the station, waiting to be shunted forward, several had managed to break out of the trains and, being shot at all the while, had made for the thicket. Zabecki wrote about what happened next:

One of the SS men who had arrived at the station that day – he was Kurt Franz, deputy commandant of the camp – came out with his dog along the road. The dog, scenting something, pulled the SS man after it into the thicket. A Jewess was lying there with a baby; probably she was already dead. The baby, a few months old, was crying, and nestling against its mother’s bosom.

The dog, let off the lead, tracked them down, but at a certain distance it crouched on the ground. It looked as if it was getting ready to jump, to bite them and tear them to pieces. However, after a time it began to cringe and whimper dolefully, and approached the people lying on the ground; crouching, it licked the baby on its hands, face and head.

The SS man came up to the scene with his gun in his hand. He sensed the dog’s weakness. The dog began to wag its tail, turning its head towards the boots of the SS man. The German swore violently and flogged the dog with his stick. The dog looked up and fled. Several times the German kicked the dead woman, and then began to kick the baby and trample on its head. Later he walked through the bushes, whistling for his dog.

The dog did not seem to hear, although it was not far away; it ran through the bushes, whimpering softly; it appeared to be looking for the people. After a time the SS man came out on to the road, and the dog ran up to its ‘master.’ The German then began to beat it mercilessly with a whip. The dog howled, barked, even jumped up to the German’s chest as if it were rabid, but the blows with the whip got the better of it. On the ‘master’s’ command it lay down.

The German went a few paces away, and ordered the dog to stand. The dog obeyed the order perfectly. It carefully licked the boots, undoubtedly spattered with the baby’s blood, under its muzzle. Satisfied the SS man began to shoot and set the dog on other Jews who were still escaping from the wagons standing in the station.

Zabecki gave an account of the goods being transported from the death camp:

Women’s hair was sent too. The load was referred to as military consignment ‘ Gut der Waffen SS.’ Everything was sent to Germany or sometimes to SS-Arbeitslager in Lublin, either one car at a time or the whole train. Fifty cars were dispatched with one consignment letter on 13 September 1942 as ‘Bekliedungsstucke der Waffen SS, military transfer No. 6710002 to Lublin.

He added:

The cars of the train were labelled. The officers checked if the windows were closed and the doors of the cars sealed. The cars waited at the station for the whole night, and if the transport was a big one, that continued even for the subsequent nights.

Franciszek Zabecki recalled what happened on the day of the revolt on 2 August 1943:

I heard shooting and almost at the same time saw the fires. They burned till 6 p.m. The SS came to the mayor and told him that anyone who helped escapees would be shot at once. There were hundreds of troops around, almost immediately; people were so afraid to be taken for Jews, almost everybody stayed locked up in their houses. The troops shot on sight at anything that moved. One woman Helen Sucha, hid a Jew: they took her up to the labour camp and she was never heard of again.

Zabecki recalled the last transports to arrive in Treblinka death camp:

After the revolt there were still transports from Bialystok. Thus, on 18 August 1943, came Pj 202 consisting of thirty-seven cars. The last transport for Treblinka came on 19 August, Pj 204 from Bialystok with thirty-nine cars. Pj stood for transports of Polish Jews.

Following the revolt the German’s took the decision to liquidate the death camp and Zabecki witnessed the trains departing through the Treblinka village station:

Such wagons left the camp on 2, 9, 13 and 21 September. On 30 September, the German railwayman, Rudolf Emmerich, who was employed to watch the transports entering the death camp, left the Treblinka station and went to Warsaw.

At the beginning of October, it was noticed at the station in Treblinka that elements of disassembled barracks, wooden planks, and chlorinated lime were being shipped out of the death camp. Later the digger-dredger machine which was no longer needed was taken away.

Zabecki witnessed the final transports that signalled the liquidation of the Treblinka death camp:

A similar transport left on 4 November, also to Sobibor – this time it consisted of three wagons with Jewish workers. On 21 October, the engines of the gas chambers and all other iron materials were sent out, probably to Lublin.

On 5 November, the armoured vehicle serving formerly to transport valuables was shipped out. Trains throughout the whole of October 1943 and part of November 1943 shipped out planks, bricks, rubble and all other construction materials. Since the beginning of the liquidation until 17 November 1943, over 100 wagons of equipment were sent out.

On 6 August 1944 when the front was very close to Treblinka and the railway station was already closed to traffic and even to railway workers. Franciszek Zabecki knowing that the station building would be destroyed, smuggled out of there some of the railway documentation concerning the traffic of transports to the death camp. A few minutes later when Zabecki was in the surrounding fields, the building of the railway station was destroyed by the Germans. Several days later, neighbouring villages around Treblinka were burned by the Wehrmacht and the local population were forced to escape to a different region. On 16 August 1944, Treblinka was liberated by the Soviet forces.

Sources

M. Gilbert, The Holocaust, William Collins, London 1986

G. Sereny, Into That Darkness, Pimlico, London 1974

W. Chrostowski, Extermination Camp Treblinka, Valentine Mitchell, London 2004

F. Zabecki, Wspomnienia dawne i nowe, Warszawa 1977

Thanks To

Robert Kuwalek for the photograph of Franciszek Zabecki

© Holocaust Historical Society June 7, 2022