Kovno

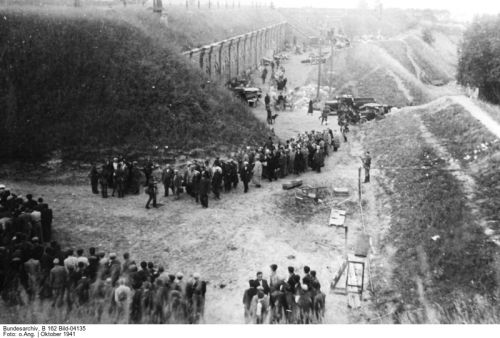

Kovno - Execution of Jews in the Ninth Fort (Bundesarchiv)

After the First World War and following the establishment of the independent state of Lithuania, approximately 25,000 Jews lived in Kovno, representing less than one- third of the city's population. The Jews were highly integrated into the life of the city, and most engaged in various branches of commerce and small-scale industry. They also worked in the liberal professions and different forms of artisanship. Conservative Judaism and modern Judaism crossed paths in Kovno, with each promoting their ideal of Jewish society. The Jews of Kovno engaged in political, educational, and social activities encompassing Jewish religious, cultural, and welfare institutions, including houses of prayer and study. Jewish schools were established in the inter-war period, including a Tarbut Hebrew school, various high schools, and a vocational school of the ORT network, whose centre was in Kovno. Evening classes and lectures in Hebrew were held, and a number of local Jewish theatres and libraries operated in the city. Books, daily newspapers, and dozens of periodicals were published in the city, predominantly in Yiddish.

Most of the synagogues damaged during the First World War were repaired during this period and the city's various Yeshivot drew students from all over Lithuania and beyond. The support and welfare institutions run by the Jewish community included a hospital, a first -aid centre, a public soup kitchen and an orphanage. Kovno served as a major Jewish political centre for various parties, including a number of Zionist parties, the Bund and Agudath Israel as well as the Communist Party, whose activities were held in secret.

After the Second World War broke out in September 1939, numerous refugees made their way to Kovno, many of them from Memel, which was annexed to Germany in March 1939. In 1940, Lithuania, including Kovno were annexed to the Soviet Union. Approximately 37,000 Jews, representing about one-quarter of the city's population, lived in Kovno at the time. During the period of Soviet rule in Kovno, the privately owned businesses were nationalised or closed, the religious and political activities were almost completely discontinued, and the Hebrew schools were shut down.

On June 23, 1941, following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, a provisional government was established in Kovno; it sought to establish an independent Lithuanian state that would be allied with Nazi Germany. On June 24, 1941, the Germans occupied Kovno. On the night of June 25, 1941, units of Lithuanian ultra -nationalists carried out pogroms in the Slobodka (Vilijampole) suburb of Kovno, across the Neris (Vilija) River. Numerous Jews had lived in Slobodka for many generations and the suburb was home to a famous Yeshiva. Approximately 800 Jewish men, women and children were murdered that night, including the community's rabbis. At the same time, Lithuanians murdered dozens of other Jews in a garage located in the heart of Kovno. The headquarters of the German 16th Army was located near the site of this killing-action, and a number of Germans witnessed the events, without interceding. This murder at the Lietukis garage will be covered in more detail at the end of this article.

In late June and early July 1941, orders limiting the Jews freedom of movement were issued in decrees enacted by the military commander and the Lithuanian Mayor of Kovno on July 10, 1941. The city's Jewish inhabitants were ordered to wear a yellow badge, their freedom of movement was restricted, they were ordered to surrender all radios and arms in their possession, and all those working in public institutions were dismissed from their jobs.

During this period, every few days the Jews of Kovno fell victim to terror and abuse at the hands of the Germans and their Lithuanian helpers. A short time after the occupation of Kovno, Lithuanians began to seize Jews on a daily basis and imprison them in the Seventh Fort, one of nine fortresses built around Kovno in the days of the Czars. Within a few days, the number of Jews incarcerated there reached approximately 10,000. In the Seventh Fort, the women and children were separated from the men, and all were abused and terrorised. They were deprived of food and water, and many were shot for any suspicious movement. A number of the women were raped by the Lithuanian guards.

On July 6, 1941, thousands of Jewish men held in the Seventh Fort were murdered, and on July 8, the women and children were moved to the Ninth Fort and released after several days. According to the report by Karl Jaeger, commanding officer of Einsatzkommando 3, altogether 2,930 Jewish men and forty-seven Jewish women were murdered in the Seventh Fort between July 4 -6. Additional Jews who were seized were brought to the Pravieniskes camp, which served as an assembly site for Soviet and Jewish prisoners. On August 7, 1941, the Lithuanians seized 1,200 Jewish men and incarcerated them in the city prison. Approximately 300 of the men were released, and the rest were moved to the Pravieniskes camp, where most of them were murdered.

The Jewish public leaders established a local council that contacted the German and Lithuanian authorities in an effort to put an end to the pogroms and abductions of people in the streets. The council members served as the core of the Judenrat, which was established at a later date. On August 5, 1941, Eichanan Elkes, a famous doctor and Zionist was elected chairman of the Aeltestenrat, and Leib Garfunkel, an attorney, was elected as his deputy. Dr. Elkes had initially refused to serve as head of the Aeltestenrat but eventually relented to pressure by the leaders of the Jewish community. A Jewish Order Service was established at the same time, under the command of Mikhael Kopelman.

Walter Stahlecker wounded by partisans on the Eastern Front (Bundesarchiv)

On July 8, 1941, Walter Stahlecker, the commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe A, issued the first orders to establish a ghetto in Kovno. The members of the Jewish Council were informed that all the Jews of Kovno were obligated to move into a ghetto to be established in the Slobodka quarter by August 15, 1941. Stahlecker attributed the creation of the ghetto to the Lithuanians' refusal to live together with their Jewish neighbours, owing to the Jews 'identification with the Soviet regime.' Stahlecker assured the Jews that they would be more secure in the ghetto and instructed the Aeltestenrat to plan and carry out the transfer. Attempts were made by the Jewish leadership to convince influential Lithuanians to avert the decree, but this was all to no avail.

By August 1, 1941, two weeks before the assigned date, more than ninety per-cent of Kovno's Jews had moved into the designated ghetto area. The Lithuanian municipality intervened during the move into the ghetto to have its area reduced. On August 15, 1941, the ghetto was sealed; the population of the ghetto numbered 29,760. The ghetto was divided into two parts, a large ghetto and a small ghetto connected by a pedestrian bridge. A thoroughfare that was not included in the ghetto area, passed beneath the bridge.

On August 14, 1941, a day before the ghetto was sealed the Aeltestenrat was ordered to recruit 500 male Jewish members of the intelligentsia on the pretext that they were needed to organise archives. After only approximately 200 men reported for work, the Germans and their Lithuanian helpers seized 534 Jewish men and murdered them all in the Fourth Fort. For a two-week as of August 19, 1941, teams of German and Lithuanian police went from house to house and carried out searches. Amidst brutality and violence, money valuables, medical and personal equipment was confiscated, during the searches. From this time onwards the Jews of the ghetto were officially permitted to possess only 100 rubles and were ordered to surrender the rest of their property to the German authorities.

On September 16, 1941, the officer in charge of the ghetto, SS-

As of mid-September 1941, thousands of men and women were sent daily to perform forced labour in the suburb of Aleksotas, where the Germans were building a large airfield. From late September 1941, onwards, numerous decrees were issued, such as Jews were forbidden to leave the area of the ghetto without permission or to bring food or newspapers into the ghetto, and a curfew was imposed. On October 4, 1941, the small ghetto was liquidated and most of its inhabitants, approximately 1,600 Jews were murdered. On October 27, 1941, an order was issued requiring all the inhabitants of the ghetto to assemble the following day in the ghetto's Demokratu Square. Gestapo officer Helmut Rauca carried out the selection, and approximately 9,200 Jews were shot the next day in the Ninth Fort. The others were returned to their homes. This day became known by the ghetto inhabitants as the day of the 'Grosse Aktion.' Approximately 17,000 Jews remained in the ghetto after the operation, mainly working for the Germans as forced labourers.

In the wake of pressure from military forces and members of the German civil administration in the Generalkomissariat Lithuania, the mass murder of Jews was halted in late October 1941, and the ghetto was turned into a centre for forced labourers, working for the German war effort. From late 1941, until the autumn of 1943, the situation in the ghetto remained fairly stable. Further decrees were issued, however, and while no additional mass killing operations were carried out, the Germans continued to kill Jews under various pretexts. On February 27, 1942, the Jews of the ghetto were ordered to hand over all books in their possession. A number of Jews who knew Hebrew sorted through over 100,000 volumes. The most valuable ones were sent to Germany whilst the rest were sent to paper-processing plants. On May 7, 1942, an order was issued forbidding women to give birth on pain of death, prompting the doctors in the ghetto to carry out hundreds of abortions. On November 18, 1942, a young man named Nachun Mak, accused of attempting to shoot a German sentry, was publically hanged. His mother and sister were subsequently murdered in the Ninth Fort.

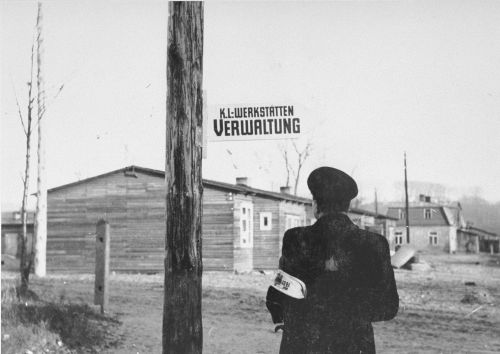

The Aeltestenrat established various institutions in the ghetto. The employment bureau was responsible for supplying workers in accordance with the German's demands. The economic committee dealt with the workshops in the ghetto; it also managed transportation as well as the bath-house, pharmacy, laboratory, cemetery, and additional agencies active in the ghetto. The nutrition committee was responsible for distributing the meagre food supplies received from the authorities among the ghetto inhabitants, while the housing committee found accommodations in the overcrowded ghetto. Also under the control of the Aeltestenrat were the fire department, health, welfare, and statistics departments, and a department responsible for schools that was active until August 26, 1942, when the Germans prohibited further schooling in the ghetto.

In January 1942, large workshops were established in the ghetto. They worked in the main for the German Army and had various departments, such as sewing, cobblers, metalwork and carpentry. The enslavement and productivity policy instituted by the Germans compelled the Aeltestenrat to devise employment solutions for the craftsmen in the ghetto; accordingly, a special workshop for graphic work was established. Similarly, the musicians were recruited into the ranks of the Jewish Order Service, in addition to performing in the ghetto orchestra, which held concerts for the ghetto inhabitants to enjoy.

Jews were sent to work outside Kovno as well. On February 6, 1942, the Germans ordered the recruitment of 500 Jews for forced labour in Riga. After the Jews defied the order, the Germans seized approximately 380 Jews in the ghetto, including 140 women and transferred them to Riga. On October 20-22, 1942, they were joined by another approximately 370 men. These Jews shared the fate of the Jews of Riga. Jews were also shipped to camps outside Kovno, such as Jonava, Kedainiai, Kaisiadorys, and Palermonas, as well as to the Babtai camp, in the summer of 1943.

On the eve of the Kovno ghetto's transformation into a concentration camp and the dispersal of its inhabitants among various labour camps, known as Kasernierung. approximately 16,000 Jews lived in the ghetto. After the ghetto was handed over to the control of the SS, it was placed under the charge of SS-

Kovno - Workshops (USHMM)

Children remained in the Kovno ghetto and labour camps, even after the killing operations that claimed the lives of the people deemed unfit for labour, in violation of the order issued by Heinrich Himmler in June 1943, that all Jews unfit for work, should be liquidated, especially the children. On March 27, 1944, the SIPO arrested all 130 members of the Jewish Order Service and brought them to the Ninth Fort, ordering them to reveal the hiding places in the ghetto. Moshe Levin, the commander of the Jewish Order Service, and other officers were severely beaten in their interrogations, but refused to divulge the hiding places. Some forty members of the Jewish Order Service were shot following their interrogations, while the few members that collaborated with the Germans were returned to the ghetto. That day, a murder operation was carried out in the ghetto to round up the children. Buses were brought into the ghetto, and the inhabitants were ordered over a public address system to hand over their children. Following a brutal search, approximately 1,000 children and a few elderly people were removed from the ghetto. The operation continued the following day, March 28, 1944, as another 300 Jews, mostly children found in underground hiding places, were also removed from the ghetto. The ghetto inhabitants managed to hide some 200 children. The same day, similar operations, targeting the children were carried out in the camps in the vicinity of Kovno, in which another 300 children were murdered.

On July 8, 1944, as the front drew closer to Lithuania, the Germans began to evacuate Jews from the ghetto and labour camps, which held between 7,000 and 8,000 people, in the direction of Germany. A number of Jews were taken on barges over the River Nemunas, whilst others were transported in cattle wagons. Thousands hid in the ghetto in underground bunkers during the deportation, and Wilhelm Goecke ordered that every house in the ghetto be dynamited and burned to the ground. Approximately 1,500 Jews were killed in the explosions between July 8, and July 12, 1944. A few underground bunkers withstood the detonations and thus approximately 90 Jews were saved. The inhabitants of the Kovno ghetto that were evacuated to Germany were sent to Stutthof and Dachau Concentration Camps, where most of them perished.

Kovno was liberated by the Red Army on August 1, 1944, three weeks after the Kovno ghetto was liquidated. In all about 3,000 of Kovno's Jews survived the war: some 2,500 were liberated in Germany and approximately another 500 stayed alive among the partisans and in various hiding places.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Photographs: Bundesarchiv, USHMM

The Massacre at Lietukis Garage in Kovno

Wilhelm Gunsilius - Report by a German Soldier including photographs

'At the beginning of the Russian campaign on the morning of June 22, 1941, I was transferred with my unit to Gumbinnen. We remained there until the following Tuesday, June 24, 1941. On that Tuesday I was ordered to transfer from Gumbinnen to Kovno, with an advance party. I arrived there with the head of an army unit on Wednesday morning (June 25, 1941).

My assignment was to find quarters for the group following us. My job was made substantially easier because we had already pinpointed a number of blocks of houses for our unit on an aerial photograph of Kovno that had been taken beforehand. There were no more significant clashes in the city. Close to my quarters I noticed a crowd of people in the forecourt of a petrol station, which was surrounded by a wall on three sides. The way to the road was completely blocked by a wall of people.

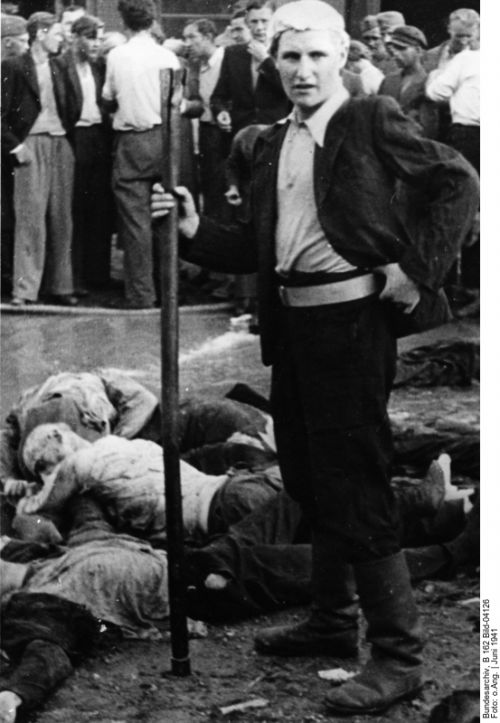

I was confronted by the following scene: in the left corner of the yard there was a group of men aged between thirty and fifty. There must have been forty to fifty of them. They were herded together and kept under guard by some civilians. The civilians were armed with rifles and wore armbands, as can be seen in the pictures I took. A young man - he must have been a Lithuanian - with rolled-up sleeves was armed with an iron crowbar. He dragged out one man at a time from the group and struck him with the crowbar with one or more blows on the back of his head. Within three quarters of an hour he had beaten to death the entire group of forty-five to fifty people in this way. I took a series of photographs of the victims. After the entire group had been beaten to death, the young man put the crowbar to one side, fetched an accordion and went and stood on the mountain of corpses and played the Lithuanian national anthem. I recognised the tune and was informed by bystanders that this was the national anthem.

Kovno - Lithuanian 'Death Dealer' at Lietukis Garage (Bundesarchiv)

The behaviour of the civilians present (women and children) was unbelievable. After each man had been killed, they began to clap and when the national anthem started up they joined in, singing and clapping. In the front row, there were women with small children in their arms, who stayed there right until the end of the whole proceedings. I found out from some people, who knew German, what was happening here. They explained to me that the parents of the young man who had killed the other people, had been taken from their beds two days earlier and immediately shot, because they were suspected of being nationalists, and this was the young man's revenge. Not far away there was a large number of dead people, who according to the civilians had been killed by the withdrawing Commissars and Communists.

While I was talking to the civilians an SS officer came up to me and tried to confiscate my camera. I was able to refuse since in the first place the camera was not mine, but had been allocated to me for my work, and second I had a special pass from 16th Army High Command, which gave me authorisation to take photographs everywhere. I explained to the officer that he could only obtain the camera, if he went through Generalfeldmarscall Busch, whereupon I was able to go on my way unhindered.'

Sources:

www. Holocaustresearchproject.org - online resource

Photographs: Bundesarchiv

Underground and Resistance in Kovno Ghetto

A short time after the establishment of the Kovno ghetto, an organisation was formed to co-ordinate the activities of the Zionist underground. This organisation was known by the Hebrew acronym for Zionist Centre Vilijampole- Kovno - Matsok. A number of its own members were appointed to the ghetto council and other institutions, in full co-ordination with the Aeltestenrat chairman and his deputy, Eichanan Elkes and Leib Garfunkel

Kovno Ghetto - Dr Elkes, Judenrat Chairman and Dr. Moshe Berman (Yad Vashem)

The members of the underground managed to make contact with the Siauliai and Vilnius ghettos, and a number of underground movements were active within a short time of the establishment of the Kovno ghetto. Among these were the Brit Zion Organisation, whose members were involved mainly in education and cultural activities and they published a periodical named 'Hanitzotz' - The Spark; the Anti-Fascist Fighting Organisation, which was founded on the initiative of the surviving members of the Communist cell in Kovno and counted among its first members, the author Chaim Yelin; and the Working Eretz Israel Bloc and Betar, whose members were active in the underground and trained with weapons. Later a joint resistance framework was established, named the General Jewish Fighting Organisation, known as JFO, which co-ordinated activities with the ghetto institutions and strove to ensure that the names of underground members did not appear on the transport lists of deportees to labour camps.

In September 1943, prior to the abduction of the Jews from the Kovno ghetto the following month, the JFO established direct contact with the partisan movements in Lithuania, with the help of a Jewish woman parachutist Gesya Glazer, who visited the ghetto in secret. Through her contact, the resistance organisation attempted to establish a partisan base in the Augustow Forest, approximately 160 kilometres from Kovno. Some 100 Jews made the trip to the forest, of whom about half were caught and killed, while most others returned to the ghetto. Two Jews, Nechemia Anderlin and Shmuel Mordkovski, succeeded in reaching the Augustow Forest, but they too, eventually returned to the Kovno ghetto.

Approximately sixty-five Jews, including members of the underground, Jewish ghetto inhabitants and Soviet Prisoners of War who were in the Ninth Fort at the time, were tasked with the burning of the bodies that remained in the fort, thus destroying all traces of the murders carried out by the Germans. On December 24, 1943, all of the Ninth Fort's prisoners escaped, nineteen of them returned to the Kovno ghetto, where they were hidden with the knowledge of the Jewish Order service, although several were recaptured by the Germans.

The resistance group in the Kovno ghetto was headed by a Jewish man named Genrikas Ziman, a teacher by profession and a Communist activist in the city. Following the failure of the Augustow Forest venture, they planned to reach the Rudninkai Forest, where the headquarters of the partisans in southern Lithuania was located. The first group, which left the ghetto on November 23, 1943, walked a distance of 150 kilometres to the forest. All of the other groups that attempted this journey were transported by a Lithuanian driver who worked for the German Security Police. He agreed to drive them in a German Police truck , in return for payment. The smuggling operation was carried out with the help of the ghetto institutions, in particular the Jewish Order Service and members of the employment bureau. In early April 1944, Chaim Yelin was apprehended while seeking out transportation for an organised group in the forest; he was tortured and killed. A few weeks later in mid-April 1944, another group set out for the forest. As the driver approached the Vilija River, near the ghetto, he stopped the vehicle. Shots were fired: four underground members managed to escape while eight others including the driver were killed in the shooting. Of the approximately 600 Jewish members of the various resistance movements, approximately 350 left the ghetto for the forests, in this organised fashion. In additional individual Jews at a later date reached the partisans in the Rudninkai Forest as well. After the murder operation against the children in March 1944, the Jewish Order Service virtually ceased to exist and was replaced by Jewish Orderlies. The Jewish Council was also disbanded and the Germans appointed Dr Elkes, as the Jewish Elder of the Kovno Concentration Camp.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Photograph: Yad Vashem

Wiener Library, London, UK

Thanks to Geoff Roach

© Holocaust Historical Society - October 3, 2018