Stryj

Stryj - A column of Russian Prisoners of War march through the city (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Stryj is located 44 miles south of Lvow. On the eve of the German occupation circa 12,000 Jews lived in Stryj. On July 3, 1941, German forces occupied Stryj and the next day a pogrom broke out, with German encouragement , during which 350 Jews were killed and a great deal of Jewish property was vandalized and looted. A few days after the pogrom, a detachment of German Security Police executed 11 Jews and 1 Ukrainian, after discovering the bodies of 150 prisoners killed by the retreating Soviet forces.

After the initial wave of violence, the Germans restored order, and a tense period of calm descended on the community. Jews were required to wear a white armband bearing the Star of David, and a Jewish Council (Judenrat) led by Oskar Huterer was established. The Jewish Police (Judischer Ordnungsdienst) was led by a man named Laufer, was also created, to enforce daily forced labour quotas, which the Germans required for construction work. A large monetary 'tribute' was imposed on the community, and the Jews also had to supply furniture and other items for the Germans. Jewish shops were marked with a Star of David, and Jews were only permitted to visit the market for two hours, between 10:00 a.m. and noon.

In August 1941, Stryj was transferred to a German civil administration and became the centre of Kreis Stryj, within the Distrikt Galizien. Dr Wiktor von Dewitz was appointed as Kreishauptmann. An office of the Security Police, commanded by SS-Oberscharfuhrer Philipp Ebenrecht, and an outpost of the Criminal Police (Kripo) commanded by SS-Hauptscharfuhrer Walther Huther were established in the city. During October 1941, a 20-man unit of Order Police (Schutzpolizei) led by Oberleutnant Albin Hauptmann arrived from Vienna. Hauptmann was later replaced by Oberleutnant Karl Klarmann in October 1942. A 70-man unit of Ukrainian Auxiliary Police (Ukrainische Hilfspolizei) led by a man named Nykolyn, supported the Germans. The Security Police office in Stryj was subordinate to the Drohobycz Border Police office (Grenzpolizeikommissariat, or GPK), led by SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Franz Wenzel, who was replaced in May 1942, by Hans Block.

On September 22-23, 1941, during Yom Kippur, the Security Police and Ukrainian policemen shot 830 Jews in the Holobutow Forest on the edge of the city. On October 2, Kreishauptmann von Dewitz ordered the establishment of a Jewish residential district - the so -called open ghetto, initially encompassing 16 streets in the old Jewish quarter of Stryj. The resettlement of the Jews into the residential district progressed slowly. In January 1942, more than 2,000 Jews were still living outside the designated area, and it was not until July 1942, that the last non-Jews were required to leave. At this time, Jewish medical personnel, members of the Judenrat, and a few craftsmen were still permitted to reside outside the district, although they could not leave the city. Approximately 4 people shared each room inside the residential district.

Jews were also required to register for work and were employed, for example in road construction, at a glass factory, and for the Heersbarackenwerke - a German firm that built barracks for the Wehrmacht. Conditions at the latter firm were good, and people prized the position there. Others, mainly women and small children inside the ghetto, worked making and repairing clothing.

During the winter of 1941 -1942, the Jews had to surrender all their winter clothing to the German army. Due to the lack of fuel, food and adequate clothing, many died. A typhus outbreak also ravaged the ghetto and the Jewish hospital quickly became overcrowded and unsanitary. At this time, a number of Jews were sent to perform forced labour in impoverished villages in the Carpathian Mountains. Only a few of them returned a few weeks later, bloated from starvation. According to a report by the mayor of Stryj, the Jewish population declined from circa 11,000 to only 9,700 during the winter months.

In the spring of 1942, the Security Police, assisted by the Schutzpolizei, and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, conducted an 'Aktion' in which they shot several hundred Jewish men, women and children. By this time many Jews had prepared bunkers and other hiding places, but the perpetrators shot many people who tried to escape or hide. In June 1942, there were 9,744 Jews in Stryj, of whom 3,930 were working. In July, reportedly 22 per cent of the Jews were dependent on welfare support, which a branch of the Jewish Social Self Help (JSS), headed by Heinrich Kronstein was distributing.

In the autumn of 1942, the GPK in Droobycz organised four deportation 'Aktions' to the Belzec death camp. The first 'Aktion' took place on September 3, 1942, when units of Hauptmann Kropelin's 5th company of the 124th Police Battalion, assisted by the Security Police, the Jewish Police and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police deported 3,000 Jews and shot an additional 400 people on the spot.

In September and October 1942, hundreds of Jews from the surrounding area were brought into Stryj, as the Kreishauptmann ordered that the villages be cleared of all but the most essential Jewish workers, for example doctors, by the end of October. The local authorities were to ensure that no Jews remained in hiding. On October 17-18,1942, a second deportation 'Aktion' occurred. 1,487 Jews were detained overnight in the synagogue, and then transported to the Belzec death camp the following morning. A third 'Aktion' took place on October 21-24, where this time 800 Jews were deported. The fourth 'Aktion' took place during November 15-16, 1942, during which 1,200 Jews were also sent to the Belzec death camp.

These deportations were badly organised and did not proceed on the basis of prepared lists. Rather the German and Ukrainian police appeared to be simply meeting a quota, seizing Jews off the streets and dragging inhabitants from their homes to the synagogue, regardless of age or employment. In the chaos, some Jews managed to hide. A few, like the teenager Friedrich Edelstein, managed to bribe Ukrainian guards to board up the windows of their train only loosely. Under the cover of nightfall, they removed the boards, jumped from the train, and made their way back to the ghetto. By the end of 1942, the Jews of Stryj, had no doubts about the fate that awaited them.

After these 'Aktions' approximately 5,000 Jews remained in Stryj, including a number of Jews who did not work, who were brought in from Bolechow during early December. Large posters announced that on December 1, 1942, an enclosed ghetto was officially declared in Stryj. The ghetto was located on Berek Joselewicz, Kugnierska, Krawiecka, and Lwow Streets, occupying a smaller area than the previous residential district. The roads leading out of the ghetto were fenced off, and the exits were guarded. Some of those who were employed and had special armbands bearing the letter 'W' were now relocated to camps established near their respective work sites, while their families remained in the ghetto. Inside the ghetto hunger reigned, and many, like the teenager Rena Goldstein, formed small knitting groups or other associations in an attempt to hold the community together.

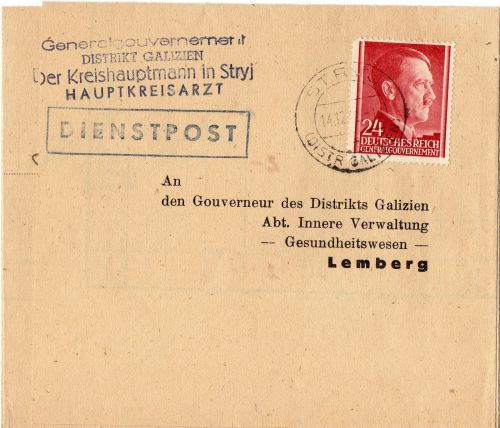

Letter from the Kreishauptmann in Stryj to Lemberg (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Conditions in the enclosed ghetto were markedly worse. Electricity and gas were cut off, and only two water pumps were available, so Jews had to stand in line for water. People stored water in the bunkers in preparation for the next 'Aktion.' The dead were taken to the cemetery on a cart pulled by a wizened old mare. Some youths wanted to obtain arms to fight the Germans and were critical of the Judenrat for its quiescent attitude to the incessant German demands.

On February 28, 1943, 1,000 people were executed by the Security Police, assisted by the Ukrainian Police, in the Holobutow Forest. Raids were conducted also in the various work camps in an attempt to find unregistered workers, who had sneaked into the camps, trying to find food and safety. Once captured these Jews were taken to the prison located at the city square, to await execution. On at least one occasion, Jews attempted to resist these roundups; one young man attempted to stab a Security Police official, and the other prisoners used the ensuing chaos to try and escape. Other searches were conducted in the ghetto where the Security Police used them as a means to uncover valuables hidden by the residents.

On May 23, 1943, 1,000 ghetto residents were deported first to the Janowska Street labour camp in the outskirts of Lvov, then to the Lublin Concentration Camp. Then on June 5 -7, 1943, the remaining 3,000 ghetto residents were shot in the Holobutow Forest.by the Security Police and members of the Ukrainian Police. According to a number of eye-witness accounts the executioners exhibited signs of heavy alcohol consumption. After the ghetto liquidation, Kreishauptmann von Dewitz reported that the mass graves had been improperly covered , posing a health danger for the general population.

In the months following the liquidation of the ghetto, the police conducted a series of searches to uncover Jews who remained in hiding. In September 1943, some 150 Jews who had been collected were executed together. Among the last to be killed were the Jewish doctors, who had continued to live together in a separate house. The labour camps in the surrounding area were also liquidated on separate occasions, on June 22, July 13-14, and August 25-26. The majority of the inmates were executed, although 70 of them were deported to Drohobycz.

Stryj was liberated by the Red Army on August 8, 1944, and several Jews emerged from hiding. Some had escaped into the woods, while others had been hidden by Poles and Ukrainians. A number of survivors returned to the city, but soon they moved on.

During 1947, several members of the Security Police unit based in Stryj were arrested in Vienna and extradited to the Soviet Union, where they were tried for war crimes. They received sentences of varying duration's, the last of them returning to Austria in 1955. On March 16, 1954, a Hamburg court sentenced Karl Klarmann to four years and six months in prison, for his role in crimes committed in Stryj. On March 18, 1959, in Vienna, Josef Gabriel, a former member of the Drohobycz GPK, was sentenced to life in prison for his participation in atrocities committed in Eastern Galicia.

Source

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012.

Photograph: Chris Webb Private Archive

Envelope: Chris Webb Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society June 22, 2021