Treblinka Labour Camp

Trebkinka Labour Camp -Kitchen Building Ruins -2004 (Chris Webb Archive)

Treblinka village is located approximately 100 kilometres north- east of Warsaw, and approximately 4 kilometres from the important railway junction of Malkinia -Gorna. which was a border station with the Soviet Union. In preparation for the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the German authorities took over a gravel pit, and used the raw materials for fortifications and other military purposes. After the gravel pit had been abandoned by the German Army, Ernst Gramms, the Kreishauptmann for Sokolow Podlaski established a company for concrete products and the need arose for a cheap labour force to work in the gravel pit. Thus, the idea for creating a penal labour camp was born, with the approval of Dr.Ludwig Fischer, the civilian governor of the Warsaw District. Later the camp received the name of Labour Camp Treblinka (Arbeitslager Treblinka).

During the camps early phase it was designed exclusively as a place of incarceration for 'stubborn elements' from the whole Sokolowski- Wegrowski district, then for the farmers unwilling to deliver their quotas of agricultural supplies demanded by the German authorities, persons evading forced labour, or involved in anti-German activity. At first the camp held only several scores of prisoners who were accommodated in the buildings formerly belonging to the gravel works, and came under the jurisdiction of the local Kreishauptmann in Sokolow.

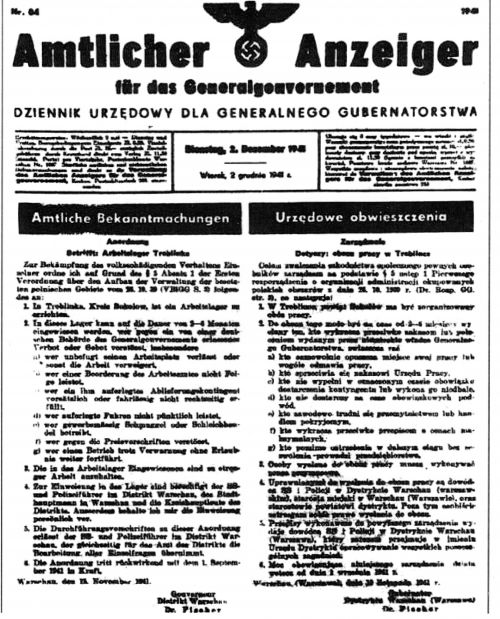

The German authorities published various notices, such as in the Official Gazette for the Warsaw District on December 16, 1941, announcing that Arbeitslager Treblinka had been set up under the jurisdiction of the SS and Police Leader Warsaw.

The Commandant of the camp was SS-

'Near the entrance to the work camp where I served there was a barrier and a guard tower. The portion of the camp that contained the prisoners was isolated from the camp in general. This area that contained the prisoners was surrounded by a double barbed wire fence, which in turn contained a patrolled region between the two fences. This controlled region consisted of a strip of ploughed earth where the footprints of anyone who crossed it would be left. The entire camp was surrounded by a single barbed-wire fence, there were buildings situated in the camp that held clothing, there were also warehouses and stables.

There were barracks where the guards lived and there were barracks where the Germans from the camp administration lived. None of the guards were permitted to enter the area where the prisoners were kept, and the guards were forbidden from entering the controlled area. The area containing the prisoners was divided into three sections. One section contained a kitchen, stoves and sewing shops. The Jewish prisoners who were artisans lived there, along with Jewish tailors, barbers, stove workers and drivers. They were dressed in civilian clothes, each wore their own clothes. In the next section lived the Jews who were used for forced labour. They were dressed in striped uniform and they wore wooden clogs on their feet. I do not know if there were skilled labourers among these Jews, who had a speciality. They were sent to work in the sand pit where they hauled sand; they were also taken to work in the forest removing tree stumps. The sand from the sand pit was sent off in the direction of Malkinia station. In the third section of the camp were kept the Polish prisoners. As a rule, the Poles were used for auxiliary work in the camp - they were dressed in civilian clothes, like the Jewish skilled workers. I do not know if their food was on the same level as that of other prisoners.

The guards were divided into sections, platoons and companies. The camp's administration was made up of Germans only - they occupied the supervisory positions. The guards were divided into four sections, each containing 12 -15 men. Besides providing security for the camp, the guards took the prisoners to work by convoy and they guarded them during work. I do not know who shot prisoners on the way to work. I personally had occasion to take prisoners by convoy to the sand pit and accompany them into the forest to remove tree stumps and to auxiliary jobs - in general wherever they went to work. I also led prisoners by convoy to Malkinia railroad station where they worked at unloading and stacking.'

The history of the labour camp was closely connected with the history of the death camp - Polish and Jewish prisoners from the labour camp participated in the construction of the death camp. The Labour Camp at Treblinka therefore served not only as a concentration camp for 'criminal elements,' it also served the function of a reservoir of manpower for the construction of the extermination camp.

Jan Sulkowski, a Polish bricklayer by profession, had been sent to the labour camp on May 19, 1942, for evading forced labour for the German authorities. He was released in the summer of 1942, after helping with the construction of the death camp. This was a typical term of imprisonment which usually lasted from two to six months, after which time the prisoners were either released or sent to a concentration camp. During his time at the Labour Camp, he witnessed the arrival of Jews in the camp, and Jan Sulkowski recalled their brutality and murderous behaviour of the camp guards towards these Jews:

'Germans killed Jews at work by shooting them or beating them to death with sticks. I saw two such cases in which SS-men, during the grubbing-out jobs forced Jews to walk under the falling tree by which they were crushed. In both cases several (two, three or four) Jews were killed. It also happened that SS-men would often rush into the barracks where drunk or sober, they went on shooting at the Jews who were inside.'

Israel Cymlich, a Polish Jew, a baker by profession was deported to the Treblinka Labour Camp from the Falencia ghetto on August 20, 1942, and he described in his memoirs, 'Escaping Hell in Treblinka,' his arrival at the Labour Camp:

'Our car pulled up at the Treblinka Labour Camp. A tall SS-man accompanied by guards, came over, and we were escorted to the camp. Above the entrance we saw an innocent-sounding sign: 'Arbeitslager Treblinka.' Noticing double barbed wire and elevated platforms in the four corners of the camp, I realised we were in for hard times. We were told to form a column of three persons abreast, and under threat of being sent to the 'forest,' to hand over money and valuables. We realised that executions took place in the forest. Most people handed over everything, they had on their person and I, too, parted with 600 zloty. We were terribly thirsty and could barely stand on our feet. Finally, some black coffee and water was brought in.

Each of us got 200 grams of bread, half a spoonful of marmalade and sugar. In the evening, together with others, we lined up for a roll call. The SS-men counted us, and we went inside the barracks. It was a fairly long barrack, lined on both sides with two-tiered rows of bunk beds, so that people slept beneath and above. The floor was made of asphalt. Most of the residents of this barracks (C) were German and Czech Jews.

Treblinka Labour Camp - Barracks Foundations 2004 (Chris Webb Archive)

The average number of prisoners in the penal labour camp amounted to approximately 1,000 to 1,200 people. Poles and Jews, who were all forced to work under brutal conditions, with very low rations. Between 800 and 900 prisoners toiled from dawn to dusk, either in the gravel pit, where the work was exhausting, digging out gravel and sand or loading railroad trucks.

Treblinka Quarry - 2004 (Chris Webb Archive)

Another group of prisoners were employed at Malkinia railroad station where they too, loaded railroad trucks. Female prisoners were employed on the farm attached to the camp, while another group consisting of 250 Jewish skilled artisans worked in the camp's workshops. Throughout the long day's labours, the prisoners were brutally treated, beaten, tortured or simply shot for the slightest misdemeanour, with only a brief respite from the back-breaking work at noon each day.

The camp diet, consisted of half a litre of watery soup or ersatz coffee in the morning, one litre of the same soup at noon, and a cup of ersatz coffee without sugar, with 20 dkg of black bread in the evening. On such a diet, bereft of any nourishment, the prisoners succumbed to diseases; epidemics spread throughout the camp resulting in a high mortality rate.

Israel Cymlich in his memoirs described the camp garrison, listing not only their names, but their characteristics:

' The Chief of the entire camp was a Hauptsturmführer, some kind of Baron (Theodor van Eupen) who had his headquarters in Ostrow Mazowiecki. He hardly ever came into direct contact with the Jews, and was responsible only for the Treblinka camp.

The camp commandant was Untersturmführer Prefi, a madman and a thug, a great fan of shooting people to death at every opportunity. He often carried out massacres, single-handedly, by shooting from a hand-held machine-gun at a group of Jews assembled for roll-call.

The Labour -force commandant was Untersturmführer Heinbuch, known as the 'thug in white gloves.' He was gifted with a phenomenal memory, recognised people well, did not cause a mess like others, granted favours to some, and surrounded himself with Jewish informers.

The commandant of the guards was Unterscharführer Stumpe. He always carried his knout, and very much enjoyed hitting everyone over the head with it, including the guards. He was especially fond of urging people to work harder by calling out, 'Tempo, tempo, cali, cali!' which earned him the nickname of 'Cali' among the guards.

Unterscharführer Lindeke was the manager, his deputy was Hagen, who left for Warsaw after some time. He often visited the camp to attend drinking bouts. After getting drunk, he liked to play cat-and-mouse with the Jews, and would kill at least a dozen of them.

The supervisor of the workshops was Unterscharführer Lanz , a boxing fan. I have no words to describe his humiliating treatment of people. He didn't treat his own people badly, but woe to anyone who became his target.

Rottenführer Werhan was in charge of the stable and the farm, he treated his own people fairly.

Finally, there was the notorious henchman of the camp, head of the group of prisoners working in Malkinia. Unterscharführer Schwarz, allegedly a butcher by trade. He derived sadistic satisfaction from tormenting, torturing and killing. He usually killed with a club, a hammer, or some other blunt instrument. Malkinia was the worst place to work in the entire camp. Every day, more than a dozen corpses of people whom he had tortured to death were brought in from Malkinia.

The penal labour camp existed from December 1941 until August 1944, when it was liquidated. The camp guard Alexey Kolgushkin, whose platoon was on patrol duty on the day the camp was liquidated recalled in his post -war testimony:

'The work camp in Treblinka, where I continued to serve, was in existence up to approximately early August 1944, after which it was destroyed. We, the guards were not informed of this. In the morning the Germans came and told us, we would have to increase camp security. I saw that a Gendarmerie was approaching from the town; the Gendarmerie was coming on the eve of the liquidation of the camp. On the day the camp was destroyed, our division was on patrol duty. Supplementary patrols were deployed next to ours in order to guard the area where prisoners were being held. On that day our division was at normal strength, however, in the morning camp security was, as I said strengthened.

At approximately 8 or 9 a.m. the prisoners began to be lead out by the Germans and were assembled in the yard. The guards who were not on patrol also participated in this. After they were all assembled, they began to beat them in groups of five and forced them to the ground. After counting out a certain number of prisoners they raised them up and made them pull their pants down to their knees, so they could not run, and in these groups they were led out into the forest, where in previously dug holes, they were all shot. The above mentioned holes had been dug in advance by the condemned themselves; they were led there by convoy by the guards, including myself. I did not know what these holes were for and I understood their purpose only on the day the prisoners were executed. In all there were several holes dug in the forest, the exact number I do not remember; they were approximately 40-50 metres in length and 4 -5 metres in width. Approximately 500 -600 prisoners were executed in these holes in all. This figure is an approximate one, since I did not count the number of people condemned to death. I only remember that when I walked to these holes the second day, I saw that they were filled up with bodies and dirt. After the liquidation of the camp the Germans and the guards fled together, since Soviet troops were already advancing on Treblinka. With the onset of Soviet troops I retreated with the Germans, first to Czechoslovakia, then to Germany.'

Post -war investigations by the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland revealed that at least forty mass graves containing the remains of 6,500 prisoners lie within half-a- kilometre of the penal labour camp . Throughout the existence of the camp at least 10,000 people passed through its gates.

Sources:

Chris Webb & Michal Chocolaty, The Treblinka Death Camp: History, Biographies, Remembrance, Ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart 2014

OSI/ DJ, Washington DC, Aleksy Nikolaevich Kolgushkin, September 24, 1980

Photographs - Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018