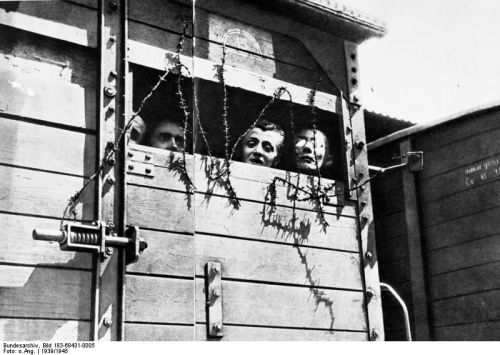

Warsaw ghetto - Grosaktion Summer 1942

Warsaw Ghetto - Street Round-up 1942 (Holocaust Historical Society)

On July 15, 1942, the German team arrived in Warsaw that had carried out the deportations in the Lublin District that spring, at the start of the enormous Aktion that was later known as Aktion or Einsatz Reinhardt, named after the moving spirit behind the destruction of European Jewry, Reinhard Heydrich.

Experienced SS-men now arrived to direct the extermination aktion in Warsaw and in other locations within the Generalgouvernement. The commander -in-chief was SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Herman Julius Hofle, whose headquarters in Warsaw was at 103 Zelazna Street, in the building that became known as the Befehlstelle. The team included a dozen or so German SS-men and Gestapo, Latvians, Ukrainians and Lithuanians. The second centre in the ghetto for Aktion Reinhardt was in the headquarters of the Jewish Order Service, at 17 Ogrodowa Street , where SS men based in Warsaw and Gestapo members were posted. These included men who had contact earlier with the ghetto as part of their duties in the SS or SD.

Two employees of the section IV-B of the Security Police and Security Service were very active in the period of the occupation and the deportations from Warsaw, were SS-Untersturmfuhrer Karl Brandt, and SS-Oberscharfuhrer Gerhard Mende. These two men decided on the course and tempo of the Aktion. Karl Brandt was indefatigable, and seemed to be omnipresent. He is remembered for the fact that during selections he never even bothered to even glance at the person's documents, but decided their fate by his visual impression of them and his mood at the time. He was reputed to be mercurial, and his fits of rage wrought destruction on countless numbers of people.

Gerhard Mende, on the other hand, was a quiet man, self-possessed, and highly diligent in his work. He was among the officers who freely graced documents with the SS-SD stamp, which gave their bearers a false sense of security, yet a few days later he would lead his men in an Aktion and totally ignore those very same documents. The division of duties and competence between the two deportation centres - the one in Warsaw and the one in Lublin is unclear.

On July 22, 1942, the deportation of the Jewish inhabitants of the Warsaw Ghetto, to Treblinka, with its murderous gas chambers began. The deportation had its own dynamics. Initially, the Germans declared that they did not intend to deport all the Jews, leaving open various escape routes and possibilities of evasion. This meant that everyone began to try to get into the category of people who would remain in the ghetto. At first for ten days employment certificates were honoured, but they later gradually lost their value. They set the Warsaw people against the refugees, allegedly freeing the community of unproductive elements.

The Jewish Order Service were promised personal safety and the safety of family members, even uncles, in-laws, and distant relatives. Later safety was promised to those employed in the shops, as opposed to other forms of employment, and then they set one 'shop' against another. Then women and children in the 'shops' themselves. Later they separated less healthy workers from those who were stronger. Better and worse 'shops,' red stamps, constantly tightening the noose.

The Jewish Order Service played an important and truly a disgraceful role in the deportations. This was undoubtedly the case in the first phase of the deportations. The Jewish policemen - Sluzba Porzadkowa (SP) directly carried out German orders. The modus operandi of the Aktion was to blockade a particular house or several houses or streets. The Germans decided in what order inhabitants of the ghetto would be deported. 'At dawn an officer of the Jewish police opened a sealed envelope, in which there was a sheet of paper detailing the streets and housing blocks which were to be shaken out on a given day.' The blockade of a house began with detailing there a team of ghetto police, fifteen to twenty-five men under the command of an SP officer. The gate and all ways out were closed. The residents were driven into the courtyard, where their documents were checked. Those who had 'good' documents could stay, while the rest were taken under escort, in horse-drawn carts, or on foot, to the Umschlagplatz.

The Germans or Jewish policemen went through the flats, checking whether anyone remained. Those found hiding were usually killed on the spot or sent to the Umschlagplatz. During the initial stages of the Aktion, the Jewish policemen were notorious for their cruelty and corruption. During the deportations three groups of Jews were untouchable: policemen, grave diggers and carters. The Germans took care of the horses that pulled the carts, that transported people to the Umschlagplatz. They were given full military rations - oats, straw and hay - directly from the stores of the Truppenwirtschaftslager der Waffen in Zoliborz.

In the Umschlagplatz people were loaded onto trains. Some of the young men were sent to the Durchgangslager, from which they were taken to labour camps. Some of the elderly, the sick, or the infirm were shot on the spot, or were shot in the Jewish cemetery. As a result of various appeals by managers of the Jewish 'shops,' Jewish policemen who had been bribed or were friends of those caught, and doctors from the hospital, a small number of those caught were released; the majority however, were taken to the Treblinka death camp.

It was often necessary to wait for the trains , so the Jews sat on the ground or in the buildings at the Umschlagplatz. Sometimes they waited all night. The Germans appointed as commander of the Umschlagplatz Mieczyslaw Szmerling, a deputy district commander of the Jewish Order Service. After a few days he was promoted to District Commander on Karl Brandt's orders, as well as chairman of the Anti-Epidemic Section. Jozef Rode- Rucz, an SP district officer, who at one time was in charge of the Central Prison for Jews in Warsaw, a former NCO in the Foreign Legion, acted as Szmerling's deputy.

Warsaw Umschlagplatz - Jewish Order Service Unit (Holocaust Historical Society)

The Umschlagplatz itself, before the deportation Aktion was the scene for the trade in goods between the ghetto and the Aryan side, became a symbol of the extermination Aktion. The topography of the place was described by Samuel Puterman:

'The area in which the Jews were collected, which was in fact a loading yard, was surrounded by its own wall, dating from before the war. There were two gates leading into the square, one from Dzika Street and the other from Niska Street. Next to the latter stood the baths building and alongside it the enormous modern blocks of prewar schools , where the infectious diseases hospital was housed. The two huge modern buildings with beautiful big rooms and wide windows also had two connected courtyards that came up to the fence of the loading yard proper.'

What went on at the Umschlagplatz stayed forever in the memory of those who were there. People with bundles and knapsacks crowded into the square. Everyone clung to the hope that perhaps the journey would not end in death, and therefore some things would be needed. And so people took warm clothing, shoes, a towel, soap, a spoon - the absolute basics. But the overcrowding was so great that hanging on to a modest 6-7 kilos of baggage became impossible. So knapsacks were usually discarded.

The desire to escape from this packed and stinking square was an instinctive reaction. Everyone was standing in feces and dirt. People waiting for the trains had to relieve themselves on the spot, where they were standing, for there was no way of passing through the crowd. To escape at all cost was an unattainable dream. Everywhere there was barbed wire, and on all sides alert German guards with machine-guns ready to fire at any moment. Some people managed to free themselves by offering valuables or money to the Jewish executioner who commanded the square - Szmerling.

Those who did not manage to get out went into the trains. The way to the train cars led along a wide road through a square with grass and flowerbeds. Several dozen meters to the left was the real gate to the loading yard. Behind the wall was an enormous square, in which there were buildings and single-track railroad lines. The proper railroad lines began beyond the square. Two hundred policemen formed two lines leading up to the trains. The cattle cars had no steps. Pairs of policemen detailed by Jakub Lejkin to each car were ordered to count the people, a hundred to each car. In less than an hour, to the accompaniment of the shrieks of those being beaten and the lament of mothers who had lost their children, sixty cars were loaded. The creaking doors were closed, the square mouths of the groaning cars. The chains creaked, and the cars moved off. Through the small windows covered with a wire grid, the last cry of despair of the tightly packed people could be heard. The train went off into the unknown.

During the deportations food rations were still brought to the ghetto, and the production of factories was still taken out. Shops were open in the evenings, ration cards became during the deportation Aktion, exceptionally valuable. Smuggling ceased completely. Jews had to rely on their stocks and the small food ration. Only ration -card bread was baked, and its price on the black market went as high as 100 zloty for a loaf in the first days of August, while it fell to 35 zloty at the end of the month, since the SS-men generally respected working bakers.

The Great Deportation Aktion - Day by Day July 21 - September 24, 1942

Tuesday July 21

About sixty hostages were arrested: members of the Judenrat - including Rabbi Ekerman, Hurwicz, Grodzienski, Gepner and Winter, and other members of the intelligentsia, including Dr. Steinsapir, who were put in Pawiak Prison. They were to be shot if the people of the ghetto did not comply with the new orders of the authorities. Some of the hostages were freed after a few hours, some were freed after a month, and the rest were finally freed in September. At 26 Chlodna Street Professor Franciszek Raszeja, who had come from the Aryan side with an official pass for a medical consultation, was murdered. He had come to see Abe Gutnajer, a well-known Warsaw antiques dealer, who was ill. Everyone in the house died, including Dr Kazimeirz Pollak. Only Gutnajer's ten-year old granddaughter survived, by hiding under a bed.

The priests from the Church of All Saints in Grzybowski Square and the Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Leszno Street received orders to leave the ghetto.

Wednesday July 22

There was drizzle. The walls of the ghetto were surrounded during the night by special units of the blue police and German auxiliary units: Lithuanian, Latvian, Ukrainian. The ghetto came under the authority of the SD.

Marceli- Reich-Ranicki, then head of the translation bureau of the Judenrat, recalled that at about 9 o'clock several cars drove up in front of the main building of the Judenrat, located at 26 Gryzbowska Street, along with two trucks full of soldiers. The building was surrounded. About fifteen SS men got out of the cars and went to the Chairman's office. The whole building suddenly fell quiet, with a stifling silence. We thought that the next hostages would be arrested. However, this time they had come about something else. Reich -Ranicki was called to Adam Czerniakow's office , where the Germans ordered him to take minutes of the meeting.

Along one side of the long rectangular table there were eight SS officers, including Hofle, who chaired the meeting. On the other side were the Jews; in addition to Czerniakow, five or six other members of the Judenrat who had not yet been arrested, and then the commander of the Jewish Order Service, the general secretary of the Judenrat, and me as secretary.

On this warm and particularly lovely day the windows on the street were wide open, to which the Sturmbannfuhrer and his men had no objection. I could therefore hear precisely how the SS-men waiting in the cars in the street were passing the time: they must have had some sort of gramophone in the car, probably a portable one, and they listened to music, by no means of the worst kind. There were waltzes by Johann Strauss, who admittedly was not a real Aryan.

Hofle began the sessions with the words, 'Today the deportation of the Jews from Warsaw begins. You know that there are too many Jews.' Jakub Lejkin was appointed commander of the Order Service; he had since May 2, 1942, been acting head of the SP after the arrest of Szerynski. Institutions formerly independent of the Judenrat were now made directly responsible to the chairman of the Judenrat: these included the Supply Section, Jewish Social Self-Help, the Association for Supply of the Products of Jewish Industry, the Cooperative Bank, the Health Office, the Union of Craftsmen, and the garbage disposal firm of S.Heyman and Company.

At around midday, notices appeared on the walls, whose contents had been earlier dictated to the Judenrat by the Germans:

The Judenrat has been informed as follows:

1. All Jews living in Warsaw, irrespective of age or sex will be deported to the East

2. The following are exempted from deportation:

a) everyone employed by the authorities or in German enterprises who can present appropriate evidence of this

b) all Jews who are members or employees of the Judenrat at the date of the publication of this order

c) all Jews employed in firms belonging to the German Reich who can present appropriate evidence of this

d) all Jews who are fit for work, who to date have not been included in the employment process; these should be put in barracks in the Jewish District

e) all Jews who are members of the Jewish Order Service

f) all Jews who are part of the personnel of Jewish hospitals and who are in the Jewish disinfection columns

g) all Jews who are close family members of the persons named in a to f. Only wives and children are counted as family members

h) all Jews who on the first day of the deportations are in one of the Jewish hospitals and are not fit to be discharged. Unfitness for discharge must be certified by a doctor appointed by the Judenrat.

3. Every Jewish deportee has the right to take 15 kilograms of his property as baggage. Baggage weighing more than 15 kilograms will be confiscated. Objects of value, such as money, jewelery, gold etc, can be taken. Food for three days should be taken.

4. The deportation will begin on 22 July 1942, at 11 A.M.

This notice, unlike the earlier decrees of the Judenrat, was signed not with Czerniakow's name but 'Judenrat.'

The inhabitants of the ghetto tried to understand what lay behind the text of the communique. It was generally thought that 'unproductive' elements would be deported, that is, according to estimates, about 60,000 people. Those who worked would stay where they were. The majority of the inhabitants did not believe the stories of mass extermination. Many believed that at least those who were capable of work would be left alive. Initially it was thought that the people who were deported were being taken somewhere to the East, to work. It was generally known that the Germans were suffering from a catastrophic shortage of labour. It was known that in enormous areas of the Ukraine and Byelorussia there were not enough agricultural labourers. What could be simpler than the explanation that the Germans wanted to make use of the Jewish reservoir of human resources for their own purposes in the East. For this reason many people reported voluntarily to the Umschlagplatz.

Among the hundreds of people I talked to on that day, 22 July, only one person was in favour of refusing to obey. This man was truly convinced that the Germans really intended - in an yet unknown way - to get rid of all the Jews. But who was to give the signal for resistance? The masses were, in spite of earlier rumours, entirely unprepared and unorganised. The president of the Judenrat, engineer Czerniakow, the few Councillors who were still at liberty, and the commanders of the Jewish Order Service were the only ones who could have refused to carry out their orders. This group of people which was collected entirely at random, was not prepared to take any heroic steps.

Some had gotten used to be subservient to the Germans, while others were aware neither of the importance of the matter nor of the scale of the danger, and others - and they were in the majority - believed that they would be able to save some of the Warsaw Jews, and above all themselves, their relations, and the people closest to them through some manipulation or other.

The Jewish police first deported the inhabitants of the refugee centers, the young people from the hostel at 3 Dzika Street, and some of the prisoners from the lockup in Gesia Street, along with street beggars.

On this day 6,250 people were deported.

Thursday July 23

It was cool. Rain fell on and off all day.

On 23 July the SP moves into battle, Officers equipped with the day's plan of action lead groups of forty to fifty police, Their first target is the prison on Gesia Street, followed by the large shelters. There were blockades in Mila Street, Zamenhof Street, and at 42 and 44 Muranowska Street; the refugee centre at 2 Gryzbowski Square was also liquidated. In the quarantine center at 109 Leszno Street, the Dulag was set up as a transit camp for those who were to be sent not to Treblinka, but to labour camps. Postal services were suspended in the Jewish District. Parcels and incoming and outgoing letters were held by the Germans.

There was a meeting of the ghetto underground. Perhaps there were two similar meetings, since Cukierman wrote of a meeting on 22 July in Kirszenbaum's flat at 56 Leszno Street, while Berlinski described a conference on 23 July, in the premises of ZTOS, at 25 Nowolipki Street. Both mention almost the same list of participants and give a similar account of how the meeting went. The following were at the meeting / meetings: Menachem Kirszenbaum, and Izaak Schipper(General Zionists), Szachno Sagan and Hersz Berlinski (Poale Zion -Left), Maurycy Ozrech and Abrasza Blum (Bund), Jozef Lewartowski (PPR), Aleksander Zysie Frydman (Aguda), Icchak Cukierman, Szmuel Breslaw and Josef Kaplan (representing youth organisations), and Emanuel Ringelblum, Icchak Gitterman, Aleksander Landau, Jozef Sak, and Eliezer Lipa Bloch.

Firstly, they talked about the question of what could be done. Should we defend ourselves? Schipper spoke of historical responsibility, its true he said, these people might be executed, but can we endanger the lives of all the other Jews? Schipper was a good speaker. He said that there are periods of resignation in the lives of the Jews, as well as periods of self defense. In his opinion, this wasn't a period of defense. We were weak and we had no choice but to accept the sentence.

In the account he wrote on the Aryan side during the war, Berlinski recalled: 'Those at the conference were impressed by Zysie Frydman's and Schipper's speeches'. Frydman said, ' I believe in God. I believe that there will be a miracle. God will not allow the Jewish people to be destroyed. There is no sense in fighting the Germans. In a few days, the Germans can liquidate us entirely. And if we do not start fighting, the ghetto will go on existing, and then perhaps there will be a miracle. Those of my friends who lean toward the Allies should not fall into despair, but believe they will be victorious. Could they possibly doubt that the Allies will bring them liberty? Or those of my friends who lean toward revolution and the Soviet Union are convinced that only the Red Army can bring them liberty. They should therefore go on believing in their Red Army. Dear friends perseverance and faith, and we will live to see the liberation.'

In the morning, Adam Czerniakow was summonsed by the Germans to the headquarters of the Judenrat, where he received new orders from Hermann Worthoff, a member of the deportation staff from Lublin. After this meeting Czerniakow decided to end his life. Before swallowing a potassium cyanide tablet, he wrote two notes. One was to the Jewish Council executive and the other to his wife. In the first he said that Worthoff had visited him that day and told him that the expulsion order applied to children as well. They could not expect him to hand over helpless children for destruction. He had therefore decided to put an end to his life. He asked them not to see this as an act of cowardice. 'I am powerless, my heart trembles in sorrow and compassion. I can no longer bear all this. My act will show everyone the right thing to do.'

An emergency meeting of the Judenrat was called during the night, new leaders were elected. Engineer Marek Lichtenbaum, at that time Czerniakow's deputy became chairman of the Judenrat.

On this day 7,200 people were deported.

Friday July 24

Cold, cloudy, a strong wind.

Police Aktionen at Karmelicka Street, 25 Nowolipie Street, 17-29 Nalewki Street, and 29 Ogrodowa Street. Adolf Berman, who lived there, recalled: 'At 6 o'clock in the morning I was woken by unaccustomed noise. In the courtyard of the house, a large division of the ghetto police appeared, headed by several officers. They closed the gate and gave loud orders: 'All inhabitants into the courtyard! You can take 15 kilograms of baggage with you.' The frightened people ran down and showed the policemen their documents. In the first days of the Aktion, the ghetto police were relatively liberal. Those who had documents showing that they worked in the 'shops' were let go.

Those with no documents, as well as the parents and brothers and sisters of those who were working, were loaded by force into the carts. Immediately the house committee made a collection of money and bread for those who were already in the carts. Bread was brought from all sides. The policemen at this time took 120 people to the Umschlagplatz from the house in Ogrodowa Street alone.

The funeral of Adam Czerniakow was held in the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw.

Leaflets printed by Haszomer Hacair appeared, appealing to Jews not to believe the Germans and resist what the SP was doing. The leaflets called for revolt and sabotage of the decrees of the occupying power, explaining that the route from the Umschlagplatz led to death. Some Jews believed that these were a trick, a provocation by the Gestapo.

Entry into the ghetto was forbidden to Poles, who up to this time had worked in offices and businesses located there.

On this day 7,400 people were deported.

Saturday July 25

The sun came out, and it was a little warmer.

There were blockades in Nowolipki Street on the far side of Karmelicka Street. A decree appeared signed by Lejkin, the commander of the SP in the absence of Szerynski, and the real commander of the SP during the deportations. It concerned the setting up of auxiliary deportation cadres to be recruited from among Judenrat employees, doctors from the hospitals, the Emergency Services, the Thirteen, the disinfection detachments, and other community institutions. 'They went for roundups, forming in the streets double rows or extended lines and drawing all passersby into their net and taking them to the Umschlagplatz.'

Franciszek Wyszynski observed the events in the ghetto from the Aryan side, and noted: 'The liquidation of the ghetto continues. Terrible things must be happening there, if we go on the basis of the fact that from Kercelak Market they saw a Jew thrown out of a fourth-floor window. Where are they taking the Jews? We still don't know; they say that they're going to Polesie. The Germans are placing a heavy burden on their consciences, but after the war Jewish power here will be to a large extent broken, and life will be easier.'

On this day 7,350 people were deported.

Sunday July 26

A fine sunny day, 27 degrees Celsius in the shade.

The Aktion went on at 6 Solna Street, 10 and 12 Nowolipie Street, 57 Nowolipki Street.

The inhabitants of the ghetto at first did not believe that everyone being deported was going to his or her death. The truth of mass extermination was impossible to accept. 'When the neighbours talked over the events of the day in the courtyard of the house at 57 Nowolipki Street, someone came up and gave a letter to the chairman of the house committee, Schmidt, apparently from the Judenrat. It was a leaflet written by no one knew who. The leaflet explained that deportation was in fact, murder of the Jews. The inhabitants decided the leaflet was a German trick.

On this day 6,400 people were deported.

Monday July 27

It was warm.

Blockades of houses in Smocza Street, at 29 Ogrodowa Street, and 56 Mila Street. 'The long processions of people head north, toward a place by a Dzika Street checkpoint known as Umschlagplatz. The whole thing is called a roundup, a selection, an Aktion. People learn these words quickly; they're on everyone's lips. You hear the same questions over and over; 'Where's the roundup today?' Where's the Aktion?' How did the selection go on Gesia?'

On this day 6,320 people were deported.

Tuesday July 28

It was cold again; it rained several times during the day.

Blockades in Nowolipie Street and Smocza Street, in the house at 6 Walicow Street.

At 34 Dzielna Street, in the Dror kibbutz, there was a meeting of representatives of youth movements: Dror (Icchak Cukierman, Cywia Lubetkin, Mordechaj Tenenbaum), Haszomer Hacair (Josef Kaplan, Szmuel Breslaw, Arie Wilner), and Akiba (Izrael Kanal).

At that meeting, we decided to establish the 'Jewish Fighters Organisation,' recalled Cukierman. 'Just us, all by ourselves, without the parties; and we decided to amass our forces and start doing what we could.' The young people had come to the conclusion that the older party leaders, for a number of reasons, would be unable to make the decision to undertake radical measures. They decided to rely on their own strength.

Arie Wilner (Jurek) was sent to the Aryan side with the urgent task of making contact with the Polish underground. The members of the youth organisations that set up ZOB automatically became its members. At the time it was set up, the organisation had only one pistol.

On this day 5,020 people were deported.

Wednesday July 29

It was cool: it did not rain.

Blockades of houses in Kupiecka and Nowolipki Streets.

In the ghetto posters were put up with the following message: ' I announce to all residents who are subject to deportation in accordance with the decree of the authorities that every person who reports voluntarily to deportation will be supplied with food, that is 3 kilograms of bread and 1 kilogram of marmalade. The gathering point and the distribution of food will be at Stawki on the corner of Dzika Street - The Head of the Order Service.'

The Jewish police were no longer sufficient to blockade all the houses: from this time members of Operation Reinhard also took part. Blockades were to be conducted by a team consisting of 10-20 SS men, 50 -100 Ukrainians, Latvians, and Lithuanians, from the auxiliary services, and 250 -300 members of the SP.

The postal blockade of the ghetto was changed into a one-way blockade: postmen could deliver letters that arrived in the ghetto. But it was still forbidden to send any letters from the ghetto. As of this date eight Jewish policemen had committed suicide, and many had left the SP.

On this day 5,480 people were deported.

Thursday July 30

It rained from early morning to 3 p.m. It was cold even if one was wearing a summer coat.

Among others, the children from the orphanage at 27 Ogrodowa Street were deported, as well as the inhabitants of the houses at 29 and 31 Ogrodowa Street and from Walicow and Gryzbowska Streets.

The Judenrat loaned 300,000 zloty from the Municipal Board to purchase bread and marmalade for the deportees. Biuletyn Informacyjny, the underground news bulletin of the AK, described the situation in the ghetto: 'The main event, which for a week has shaken the whole town, is the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, which the Germans have begun and which is being carried out with complete Prussian bestiality... Daily more than 6,000 Jews are deported... The direction they take is to the east. The destination of the deportees is not known, but rumours suggest the region of Malkinia and Brzesc on the Bug. Nor do we know what fate lies in wait for the deportees - the most pessimistic assumptions are made on this subject.

On this day 6,430 people were deported, of whom 1,500 reported voluntarily.

Friday July 31

It was cloudy and cold; at 1 p.m. it poured rain, then cleared up and became warmer. Blockades at 52 Nowolipki Street and 31 Ogrodowa Streets.

The Ukrainians and Lithuanians stopped taking any notice of labour certificates. All the effort put into obtaining them had proved in vain. Wladyslaw Szpillman said in 1946, ' I became very depressed. I lay on my bed for days on end listening to the echoes coming up from the street. Every clatter of wheels put me into paroxysms of fear - they were the carts going to the Umschlagplatz, for no others now moved into the ghetto, and each of those carts might stop in front of our house.'

The two Turkow sisters decided to report voluntarily to the Umschlagplatz. My two sisters, Rachela and Sara, twins, loved one another so much that they could not imagine life without each other. If they did this they could go together and choose their place of settlement in the East, where while working, and doubtless working hard, they would be able to survive this tempest of war, without all the time fearing that any moment they would be caught.

Because of the constant anxiety our nerves were frayed to such a degree that we believed that they had made the right decision. We said goodbye to our dear sisters, asking them to write to us immediately, as soon as they got there, telling us how to find them, so that we could join them. When we said goodbye, wishing that we might all meet again soon, we did not for a moment imagine that we were seeing their faces for the last time, that we would never more hear of them, that we would never know where their delicate bones lay,' so wrote Janasz Turkow.

On this day 6,756 were deported, of whom 750 reported voluntarily.

End of July

Szerynski came out of prison and returned to the post of commander of the SP; he was given an extra star (the fifth) and appointed 'deportation commissar.'

German and Czech Jews, who lived in the refugee centre organised in the synagogue in Tlomackie Street, were deported. They were well disciplined and carried identical bundles each labelled with name and place of origin. Every person has a preassigned place and function. They step away in even rows of four, like soldiers in formation. The comparison is apt: Many are wearing their Frontkampferzeichen - ribbons awarded to those who fought at the front during the Great War. Some display medals, such as the Iron Cross.... They march forward in tight formation, shoulder to shoulder in perfect step. Here's a squad of sick people, propped under the arms by their fellow marchers.'

August

The Bund sent Zalmen Frydrych (Zygmunt) to follow the people deported from the ghetto. Zygmunt went on the journey following the transport. He got to Sokolow, where, as the local railwaymen informed him, 'the railroad line divided and one branch line went in the direction of Treblinka. Every day one Warsaw goods train filled with people went along this line and came back empty. There was no supply of foods. Access to the station in Treblinka was forbidden to civilians.The next day Zygmunt met two naked Jews, escapees from Treblinka, in the market place in Sokolow. They described the slaughter precisely.'

It was announced that every policeman had to bring to the Umschlagplatz five Jews, for each of whom he would receive a certificate. If at the end of the day he could not show his superior officer these five certificates,they would take members of his family, or he would be taken himself. From the windows of the house in the hospital block in Pawia Street I often saw policemen taking old people and children in rickshaws. I shall not forget the shriek of a little girl in a green coat, perhaps six years old, who was begging the policeman through her tears: 'I know that you are a kind man, don't take me, my mommy has gone out for a minute. She'll be back soon and I wont be here, don't take me,' but the lament of the little girl, which might have moved the heart of a monster, did not move the policeman. He carried out his duties in cold blood. Two hours later I saw a distracted woman running in the middle of the road in the direction of the square. She was shrieking despairingly, 'My child - where's my child.'

Saturday August 1

Fairly warm, but not hot; sunny

Blockades of houses in Dzielna Street, in houses at 20 and 22 Nowolipie Street, and at 25 Nowolipki Street.

The Aktion continues without a break. It spreads now its moving out of the poor back streets and toward a core. Whole sections have been blocked off on Leszno, Nalewki, Gesia, Sliska, and Panska. The German presence is more and more pronounced. All pedestrians and residents caught up in the blockade - several thousand people - are chased onto a street and lined up in ranks of four to six. The selection is done right there. One rank after another advances toward the SS-man: a quick glance at the papers, the face, and a flick of the crop sends each person either to the left and freedom or to the right and Umschlagplatz.

The selection proceeds calmly - calmly and politely. The German politely sends the parents to Umschlagplatz, and the daughter to freedom, the daughter politely approaches and asks to accompany her parents; the German politely consents. Politely he splits families, taking wives from husbands, children from parents, parents from children. Politely, calmly, quietly, no moaning, no cries, no convulsions. The selection is over. The third group is bound for Umschlagplatz - but how, just as they are?

It's a hot August day; everyone is dressed as lightly as possible. The women are wearing summer dresses and sandals; the children are barefoot, no one has any other wrap or hat. And that's how they're expected to ride off into the unknown? No fresh shirt, no bundle, not a piece of bread? Impossible! Where are they headed? What does it mean? After all, everyone has to take something; surely they're allowed a minimum of essential items! They are going to a new settlement, not for a few days vacation or for a picnic in the country. Autumn will be here, then winter, and they have no more than a single shirt or dress.

Notices signed by Szerynski appeared, announcing that bread and marmalade for deportation for those who reported voluntarily for deportation would be continued until 4 August.

The Warsaw underground PPR paper 'Trybuna Wolnosci (Tribune of Liberty) urged: 'The occupiers are merciless and uncompromising. The Jewish people must be similarly uncompromising in the defense of their own lives. They must find in themselves heroism, courage and contempt for death. Only uncompromising resistance in every situation, only an active approach, and not passive waiting for the slaughter, can save thousands or tens of thousands, even though sacrifices will have to be made.

We have to get beyond the boundaries of the ghetto and of Warsaw- go to the forests, to fight on against the foe. We must resist the police. Every house should become a fortress... the duty of Poles is to help persecuted Jews. Only scoundrels or fools , who do not understand that after the Jews it will be the turn of the Poles to be deported to the East, can support or enjoy this action. The Polish people along with the Jewish people must actively resist the monstrous plans of our common brown-shirted executioners.'

On this day 6,220 people were deported.

Sunday August 2

Sunny and warm.Blockades of the house at 1 Rynkowa Street and the houses on the corner of Leszno and Solna Streets

The 'shops' in which thousands of people had found temporary refuge became islands of safety. As the Aktion developed, they were surrounded by fences. All those who were not working were thrown out of the fenced territory. Those who were working were left in barracks in housing blocks allocated to this particular 'shop.' In this way the Tobbens workshop remained in the small ghetto; it occupied the area bounded by Zelazna, Panska, Twarda, Ciepla and Ceglana Streets, outside which it was forbidden to go. In the big ghetto other 'shops' were set up, in which all about 40,000 people were employed, 10 percent of the population of the ghetto.

In the Jewish cemetery, 56 Jews, prisoners from the Gesiowka, were killed.

On this day 6,276 people were deported.

Monday August 3

Warm, or even hot

Blockades in Gesia, Pawia, Smocza, and Lubecki Streets.

People tired out by almost two years in the ghetto went voluntarily to the Umschlagplatz: those who had lost hope or who counted on being reunited with family members deported earlier or who no longer had the strength or desire to struggle to survive.. 'Once a doctor we had known, Dr Sznajderman, showed up in our apartment. He said he came to say good-bye. He had decided to go to the Umschlagplatz with his ten-year old son. 'What are you doing, doctor?' my mother burst out crying. 'I can't take it anymore. I have no strength left to fight.' He had money, documents, he was safe, he could not tolerate the daily stress.'

In the cellar of the school at 68 Nowolipki Street, the first part of the Underground Ghetto Archive was buried.

On this day 6,458 people were deported, including about 3,000 who reported voluntarily.

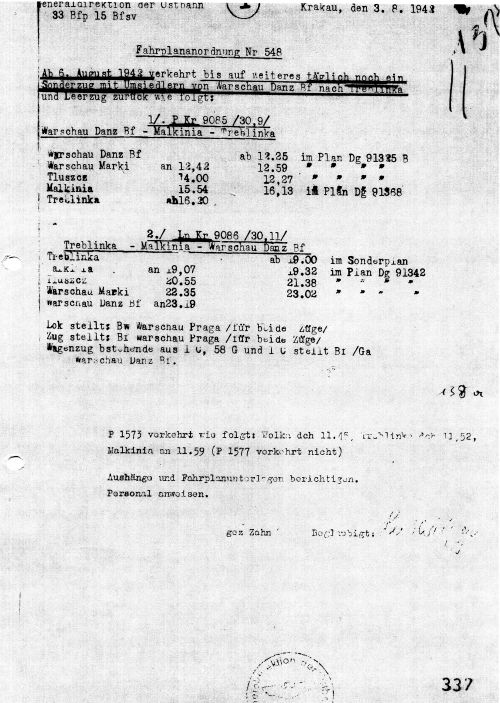

Fahrplannordnung 548 - Warsaw to Treblinka - 3 August 1942 (Holocaust Historical Society)

Tuesday August 4

In the morning it was cloudy with a cold wind, but later it cleared up, and in the evening the wind dropped, and it became warm.

Blockades at 38, 40, 42 Muranowska Street, at 45 Nowolipki Street, and in Gesia Street, Zamenhof Strret, and in the Small Ghetto.

On this day 6,568 people were deported.

Wednesday August 5

Warm, in fact hot..

Deportations from the orphanages at 77 Twarda Street and 28 Sliska Street.

The inhabitants of Janusz Korczak's Orphans' Home were deported. Nachum Remba, an eyewitness to this event, wrote: (some sources say this took place a day later on August 6th)

We were told that they were taking the nursing school, pharmacies, Korczak's orphanage and many others. It was a very hot day. I put the children from the boardinghouses at the end of the square, next to the wall. I thought that perhaps it would be possible to protect them that afternoon, keep them until the next day. I proposed to Korczak that he go with me to the Judenrat to persuade them to intervene. He refused, he did not want to leave the children even for a minute. They began the loading. I stood by the cordon of the Order Service, which led to the trains.

I stood and with a beating heart watched to see whether my plan would work. I asked all the time about the numbers in the train cars. They loaded them constantly, but they were still not full. Suddenly Mr Szmerling ordered the boardinghouses to be led out. Korczak went at the head of the column. No! I will never forget that sight. It was not a march to the trains, it was an organised silent protest against banditry. In contrast with the packed masses, who went like cattle to the slaughter, it was a march of a kind that had never taken place before. All the children were formed in fours, with Korczak at their head, and with his eyes directed upward. He held two children by their tiny hands, leading the procession.

The second column was led by Stefania Wilczynska, and the third by Broniatowska (her children had blue knapsacks), while the fourth column was led by Szternfeld from the boardinghouse in Twarda Street. They were the first Jewish ranks that went to their death with dignity, giving the barbarians looks full of contempt. When the Germans saw Korczak, they asked, 'Who is that man?'

Other teachers and workers in the orphanages of the ghetto who went with Korczak and the children to Treblinka were Roza Azrylewicz- Sztokman. Henryk Azrylewicz, Henryk Asterblum, Balbina Grzybowa, Roza Lipiec- Jakubowska, Sabina Lejzerowicz, Natalia Poz, Dora Sokolnicka, Dr. Tola Mincowa, Jadwiga Pozner, and many, many others.

On this day 6,623 people were deported,

Thursday August 6

Cool.

Blockades at 10, 23, and 25 Nowolipki Street; a big selection in the offices of Centos at 2 Leszno Street.

The Germans liquidated Kohn and Heller. They were summoned to the headquarters of the SP at 17 Ogrodowa Street. Brandt received them in a fury, his yells could be heard throughout the whole building. After a few minutes two pistoleros came out, dragging Kohn and Heller behind them. Kohn resisted, shouting, begging, his executioner dragged him by force. Heller went quietly, pale as a ghost, with his permanent smile at the corner of his mouth. They dragged them to the wall in the courtyard , threw them onto the ground, and shot them.

A Pole on the other side of the wall noted, 'Everything is falling on the exchange because in the ghetto, the Jews to get hold of money, are selling gold and jewellery for practically nothing. The emptying of the ghetto is going ahead, they are said to take out every day about 40-60 cattle cars, and allegedly they pack 100 Jews into each car, and so they are deporting daily 4,000 -6,000. According to another version they are taking out daily as many as 10,000 - 12,000 and are supposed to be going to deport all the Jews by the end of August.

It is difficult to understand the Germans, the English and American Jews will not forgive the Germans the destruction of 1 million Jews, and probably more, and with their determination they will exact a heavy revenge! In connection with the swift emptying of the ghetto it is clear that they will deport Poles into the ghetto. According to one version, which can be heard everywhere, they are supposed to be going to deport the population of Zoliborz to the ghetto: according to another version, Krakow is to be annexed to the Reich, and Poles from Krakow are to be deported to Warsaw to the present ghetto. It is awful to think what still awaits us.'

On this day 10,085 people were deported.

Friday August 7

Warm.

Twelve hundred children from the boardinghouse at 12-14 Wolnosc Street and several hundred from 18 Mylna Street were deported; the director of the latter, Aron Koninski, and his wife went with the children to Treblinka. There were also blockades in Lubecki and Mila Streets. A selection was carried out in the Landau 'shop' at 30 Gesia Street, from which they deported women and children and very many rabbis. Mendel Alter from Kalisz, and many, many others.

On this day 10,672 people were deported.

Saturday August 8

It was quite warm during the day, but the evening and night were cold.

Blockades in Zelazna and Sienna Streets.

The obligation to register ration cards in the distribution shops was lifted. In the communique signed by M.Lichtenbaum, we can read, 'Every consumer can collect his due food ration in any distribution shop on showing his ration card.'

On this day 7,304 people were deported.

Sunday August 9

Warm, but not hot; cool in the evening

The headquarters of the Judenrat - and most of its departments - were moved from 26 Grzybowska Street to 19 Zamenhof Street. At the same time, the Judenrat was instructed to make a 50 percent reduction of its employed personnel and to supply by noon the following day 7,000 persons from amongst its employees and their families for deportation.

All the Jews who lived in the small ghetto, that is to the south of Chlodna Street, were to leave their flats by Monday, 10 August before 6 p.m. In the small ghetto only the employees of the 'shops' of W.C. Tobbens and W. Doring could remain. In a period of a few hours by 6 o'clock in the evening, thousands of families had to leave their homes. At the same time, various blockades were carried out in the streets of the big ghetto.

An exceptionally large number of people were killed in the streets of the ghetto. The slaughter lasted from the morning to half past nine or ten at night. Bands of soldiers of various nationalities, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, under the command of Germans forced their way into flats and shops, robbing and murdering without mercy.

On this day 6,292 people were deported.

Monday August 10

It was not hot.

Blockades in Chlodna Street and in the School of Nursing at 1 Marianska Street. Earlier documents ceased to be valid, and it is now necessary to have an additional SD stamp on them. The identity cards of the ZSS, Judenrat Department of Schools, and others lost their validity.

On this day 2,158 people were deported.

On about 10 August a member of the Haszomer Hacair, Dawid Nowodworski, escaped from Treblinka and returned to the ghetto. He recounted what he had seen there. 'Today we had a long talk with Dawid Nowodworski, who returned from Treblinka,' recalled Lewin. 'He told us in detail about all the sufferings that he had been through from the moment he was caught to his escape from the place of execution and his return to Warsaw. What he said again confirms what we already know and proves beyond doubt that the people from all the transports were killed and none of them could have survived. And this means both those whom they caught and those who reported voluntarily. That is the naked truth. Terrible,'

Tuesday August 11

Warm, but not hot.

Blockades in Chlodna, Franciszkanska, Bonifraterska, Muranowska, and Nalewki Streets. In one of the courtyards in Chlodna Street, the painter Roman Kramsztyk was murdered.

The Aktion continues... Two or three SS-men show up where the SP is conducting a round-up and terrorise the population with their yelling, their whips and their shooting. People are killed. It all takes place at a dizzying tempo, faster, faster, on the double! Soon all the residents are standing in the courtyard; the selection is over; those who will return to their apartments have been separated from those who will never see their homes again. There's no time for going back, no time for a final look around, no time for any last words. Even though the proper pace for funerals is slow and dignified, you aren't allowed to walk slowly. Here you have to run. Faster, faster on the double!

On this day 7,725 people were deported.

Wednesday August 12

It was raining in the morning, but later it cleared up and was quite warm.

Blockade in the Landau 'shop' in Gesia Street. Abraham Lewin's wife Luba, was among those taken.

On this day 4,688 people were taken.

Thursday August 13

It rained almost all day; it was quite warm

Blockade at 15 Leszno Street; a big blockade in the Tobbens 'shop' in Prosta Street, from which 3,600 people were taken to the Umschlagplatz, mainly women and children.

Informacja Biezaca volume 29 reported: 'The liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto continues, and from the 6th of this month, the pace has been stepped up. The total silence of British propaganda is surprising - since the 22nd of last month there has not been a single communique on the matter, The last week has been marked by:

1) raising the contingent deported to 10,000 daily

2) total removal of Jews from what is called the small ghetto on the 12th of this month

3) ruthless removal of old people, cripples, and the disabled (50-80 daily from the beginning of this Aktion

4) fruitful co-operation with the Jewish militia

5) the beginnings of a new form of organisation of those Jews remaining alive: closed workers barracks. The number of murdered and deported is now approaching 150,000.

On this day 4,313 people were deported.

Friday August 14

Warm.

Blockades in Karmelicka Street and in the Schultz 'shop' in Nowolipie Street. On this day 5,168 people were deported, including the daughter of Rabbi Szapiro.

Saturday August 15

Warm in the evening it was 23 degrees Celsius

The Jews were ordered to move out of portions of the following streets Nowolipki, Nowolipie, Dzielna, Smocza, Pawia, Wiezienna, Lubecki, Gesia, Okopowa, Giinianna, Zamenhof, Nalewki, Walowa, Franciszkanska, Mylna, and Leszno, where workers in the 'shops' were to be quartered. Trams no longer ran through the ghetto.

On this day 3,633 people were deported.

Sunday August 16

Warm.

A blockade was set up in the headquarters of the Judenrat, and many Judenrat officials were deported, as well as those from the ZSS and other institutions. Selections took place at the labor site in the Umschlagplatz, where the things belonging to those being deported were sorted. Wladyslaw Szpilman worked on this labor site. His whole family - his parents and three siblings - had gone off in the cattle cars. 'I suddenly heard somebody shouting: 'Look, there's Szpilman!' Someone grabbed me by the collar and I was thrown out beyond the police cordon. I did not want to be separated from my family: I pushed forward between the policemen's shoulders and shouted to the family, completely terrified that I might not, at the most important moment, be able to get through to them and be separated from them forever.

One of the policemen looked at me and said in disgust: 'what do you think you're doing, save yourself.' In a fraction of a second, awareness of the fate of these people being loaded into the cattle cars hit me like a revelation. My hair stood on end. I looked around - over there was free space. I tore off in the direction of those streets, driven by animal fear - Wlayslaw Szpilman

On this day 4,095 people were deported.

Monday August 17

Warm

Blockades at 25 Leszno Street

On this day 4,160 people were deported

Tuesday August 18

Warm

Selection in the brushmakers 'shop' in Swietojerska Street. The Germans took about 1,600 people from there, including Rabbi Szymon Huberband.

On this day 3,976 people were deported

Wednesday - August 19 -21

Warm, or even hot. The nights are warm too, and you can sleep with the window open, which you couldn't do in July. A strange thing, the summer -June and July was cold, and in August autumn usually begins: but the temperature in August is what it should have been in July.

A break in the Aktion. The Germans were deporting Jews from the Warsaw District, including Otwock, Miedzeszyn, Falenica, and Minsk Mazowiecki. In Warsaw it was quiet at this time, and about forty hostages who had been held since 21 July were released.

Thursday August 20

Warm, in the evening it was 26 degrees

There was an assassination attempt on the commander of the SP, Jozef Szerynski. This was carried out on the orders of ZOB by Izrael Kanal, a ZOB member who had earlier served in the SP as an underground spy, and knew Szerynski. At the beginning of the Aktion, Kanal had left the SP, but when necessary he would put his hat back on.

On this particular day, 'he put on his uniform. He came to police headquarters and tried to shoot Szerynski, but his gun jammed for some reason. Then he shot a second time and hit his cheek. He thought he had killed him- we learned only later that the man was only wounded; he jumped on his motorcycle and headed for Nalewki, to the gate of the ghetto, to divert his pursuers, and came to Dzielna'.

This attempt on the life of the head of the SP made a big impression on the inhabitants of the ghetto. It seemed so strange that Jews had gone so far as to commit an act of armed terror that even Lewin, who had contacts with the underground, noted: 'Apparently he was wounded by a Pole, a member of the PPS, who dressed up as a Jewish policeman. Szerynski committed suicide on 24 January 1943.

During the night the first big air raid was launched against Warsaw by Soviet planes

About August 20

ZOB published a leaflet, accusing the Jewish police of acting against the Jewish people, and announcing that a death sentence had been carried out on Szerynski. Members of the ZOB set fire to empty houses, so that Jewish property would not fall into the hands of the Germans.

Friday August 21

Warm

ZOB received its first arms from the Aryan side: five revolvers and eight grenades from the PPR.

In the ghetto the German megaphones known as 'barkers' which broadcast the orders and communiques of the occupying power in Polish, fell silent. According to Horowitz after the end of the deportations only one megaphone was in use, in Muranowska Street.

Saturday August 22

Hot

The Germans had not yet returned to the ghetto. Blockades including one in Pawia Street were conducted by the Order Service, which with unprecedented brutality caught mainly women and children.

Sunday August 23

Hot

Stanislaw Srokowski noted in his diary 'The tragic news of the murder of the Jews in Falenica, Otwock, and Minsk Mazowiecki. They are killing mainly sick and old Jews, women and children. The bombing of Warsaw during the night of 20-21 of this month made an enormous impression. Many bombs were dropped, at any rate they must be counted in the hundreds. Many houses were damaged- Marszalkowska Street, Unia Lubelska Square, Frascatti Street. A house in Zlota Street was damaged, the Omega clinic, the airport at Okecie, etc. The bomb that fell in Warsaw at the corner of Swietokrzyska and Zielna Street killed outright twenty-nine people who had congregated on a porch. Looters at once appeared on the scene and took 15,000 zloty from the pocket of one of those killed. A German soldier, who wanted to pick up an arithmetograph (calculating apparatus) was shot on the spot by an officer.

Monday August 24

Warm

The Aktion in the ghetto was still being carried out by the Jewish police. Abraham Lewin noted 'What can be done with Mother? Old people are in a hopeless situation. They have nowhere to go. I agreed it would be better to put her to sleep forever than hand her over - in the case of extreme danger - to the executioners.

A meeting of Oneg Shabbat in which Ringelblum, Gitterman, Bloch, Lewin, Gutkowski, Feld, Winter, Kaplan and Landau took part.

From 19 to 24 August about 20,000 people were deported.

Tuesday August 25

Hot. Full moon.

The Germans returned to the ghetto. Blockades at 19 Zamenhof Street and in Pawia, Gesia and Lubecki Streets; a further selection in the offices of the Judenrat. The Karl Heinz Muller 'shop' in Mylna Street was liquidated; among the workers there were many artists. They were all deported. 'All the 'shops' were given instructions concerning the maximum number of workers they had the right to employ.'

In the Berman's flat at 4 Lubecki Street there was a meeting about the current situation of those working with Centos and other community organisations. During the meeting there was a blockade of Lubecki Street and three neighbouring streets. The Bermans were taken to the Umschlagplatz, from which they were later taken out by a Jewish policeman Konhajm. This cost them 200 zloty

On this day 3,002 people were deported.

Wednesday August 26

Terribly hot. At 8:00 in the evening it was 29 degrees

Selections in the 'shops' including the Landau 'shop' (OBW - Ostdeutsche Bautischlerei Werkstatte) at 30 Gesia Street.

Deportation of about 3,000 people.

Thursday August 27

Hot, 32 degrees in the shade, unbearably close

Blockades at 14 Pawia Street, selection in the Judenrat and in the Oschman- Leszcynski 'shop' in Nowolipie Street. In a report on the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, Antoni Szymanowski wrote: 'The world stays silent. The world knows what is going on here - it cannot be otherwise - and stays silent. God's vicar stays silent in the Vatican, the defenders of the righteous cause are silent in London, in Washington, the Polish Government in Exile is silent, the Jews of Europe and America are silent. The silence is terrifying and amazing.

Meantime the voice of protest can be heard not from the free world but from where it is most difficult for it to speak, from the depths of slavery. All Polish independence, military and ideological organisations - rising above the differences that divide them, conquering the poison of German propaganda and their own prejudices, reservations and dislike, which are sometimes very profound - have united to condemn the German barbarity.

I by no means deceive myself that everyone in Poland thinks alike - but those who have taken on themselves responsibility for the fate of their homeland think like this, and these are the only ones who have the right to speak in its name.

On this day 2,454 people were deported.

Friday August 28

Hot, the temperature indoors in the evening was 28 degrees

A break in the Aktion

Saturday August 29

An awful heat wave

Selection in the Brauer 'shop' in Nalewki Street

Sunday August 30

A little cooler in the night, but a dreadful heat wave in the day time: 28 degrees in the evening.

A selection in the Schilling 'shop' in Nowolipie Street.

Monday August 31

Cloudy in the morning, rain in the afternoon, a cool evening, cold at night

A selection in the Hallman 'shop' at 59 Nowolipki Street

Tuesday September 1

A little warmer

Blockade in the Franke and Schultz 'shop' at 37 Smocza Street

During the night another Soviet air raid on Warsaw. Bombs also fell in the ghetto, for example on the house at 4 Lubecki Street. 'Raids in the night - balm to our hearts, bitter joy that we are not alone. Everyone lives with the strange conviction that they will not bomb the ghetto. After all they are friends, only the German district will be bombed or military targets. Unfortunately, bombs fall nearby. It makes no difference, let them do damage; anything is better than a life like this- let it finally come to an end. But we want to survive. A splinter bomb fell into the house next door. People were killed and wounded. We ran to help. There were no stretchers, no bandages, no doctors. Everyone froze as they looked at the bodies.

The detonations came in quick succession. If someone could blow up the whole Umschlagplatz like that.... but there are people in the train cars. Yet a bomb would be better, a quicker end. Why are these sacrifices made? How cruel is our fate. Despite everything, it is easier now to go to sleep. Maybe it really will come to an end. This is ridiculous, where does this sudden hope come from? Because of one air raid, and in general do air raids have any decisive significance in this war? No. But even so, a warmer wave of faith enwraps the heart. Sleep peacefully, condemned man, the avenger is getting ready for a final settling of accounts, with your executioner.

From 'Informacja Biezaca volume 32' : 'In the Aryan district there are increasing numbers of denunciations of people who have escaped from the ghetto. In addition to paid spies many amateurs are doing this for gain (blackmail).

Wednesday September 2

Warm

A further blockade in the Schultz 'shop.'

A third Soviet air raid in the night: the Moriah Synagogue at 7 Dzielna Street and a house at 35 Gesia Street were burned.

Thursday September 3

Warm, even hot again: In the evening a major thunderstorm that lasted several hours.

Blockades in the Schultz and Tobbens 'shops.'

A black day for the resistance movement in the ghetto. Many underground activists had been employed, partly fictionally, in the OBW 'shop' whose Jewish manager was Aleksander Landau, the pre-war owner of the factory, who worked with the underground. This day the Germans arrested one of the leading figures of the underground, Josef Kaplan, who worked in the office of the 'shop.'

Another member of the ZOB leadership, Szmuel Breslaw was killed by the Germans in the street. At the news of the arrest of Kaplan - a few days later he was killed in the gateway of a house in Dzielna Street - and the killing of Breslaw, fearing further repressive measures, the underground decided to move all its weapons, which were in a hiding place in an OBW housing block at 63 Mila Street, to 34 Dzielna Street. Reginka Justman, an underground courier, hid these arms in a basket under potatoes. On the way, the Germans stopped her and found the arms. Reginka was taken straight to the Umschlagplatz. The underground managed to get her out. These events brought depression and a feeling of resignation and helplessness to the ranks of the underground.

On this day 4,609 people were deported.

Friday September 4

It was hot and close. In the evening there was an exceptionally heavy storm.

Blockade in the brushmaker's 'shop' at 34 Swietojerska Street, liquidation of the AHAGE- Zimmermann 'shop' at 43 Mila Street. The funeral of Szmuel Breslaw in the Jewish cemetery in Okopowa Street.

On this day 1,669 people were deported.

Saturday September 5

Hot, 28 degrees

Blockades in the Tobbens, Franke and Schultz, and Hallmann 'shops.'

In the ghetto a notice appeared with the following message:

On the orders of the Plenipotentiary for Deportation Matters, the Judenrat in Warsaw announces the following:

1. By Sunday 6 September 1942, by 10 o' clock in the morning, all Jews without exception who are in the ghetto must gather in order to register in the area bounded by the following streets: Smocza, Gesia, Zamenhof, Szczesliwa and Parysowski Square.

2. Movement of Jews during the night of 5-6 September 1942 is also permitted.

3. Food for two days should be taken and drinking vessels

4. It is forbidden to lock flats

5. Whoever fails to comply with this order and remains in the ghetto until Sunday 6 September 1942, after 10 o'clock in the morning (apart from the above -mentioned area) will be shot.

The Judenrat in Warsaw

This notice announced the last great selection of the inhabitants of the ghetto, which went down in history as 'The Cauldron (or Trap) on Mila Street.'

Sunday - Friday September 6 - 11

On Sunday it was hot. Then it began growing cooler until Thursday, but on Friday it again grew warmer.

Employment limits were set for businesses in the ghetto, and all those employed were to receive cards (or tin number plates) that allowed them to remain in the ghetto. Cards of this kind, known as 'numbers to live,' were distributed to 32,000 people. The Polish underground paper 'Strzelec' (Shooter) noted that 'everyone is obliged to wear (a number of this kind) on his chest. They are yellow cards with handwritten numbers, and the stamp of the Judenrat and a signature. The numbers do not bear a name.'

People at the head of particular institutions or enterprises had to make a list of people who would receive numbers. They had to decide whether to include single people or those with families, young people or older people, who were more experienced workers. One of the employees of the hospital in Stawki Street recalled, 'I remember a scene like this, how a young doctor, Jurek Bzura, came to the hospital and showed us a number to live - he only had one. Well, gentlemen, my mother or my wife, he asked.

The remaining inhabitants of the ghetto, the so-called unproductive element, were to be deported. The employees of the 'shops,' German firms, and labour sites passed through 'the eye of the needle formed by the narrow passage at the junction of Wolynska Street and Lubecki Street. The workers of the Judenrat, Order Service, Werterfassung and all the SS workshops on the other hand went through the little square at the junction of Zamenhof and Gesia Streets.

Antoni Szymanowski noted:

Anyone who did not see this procession will never understand the menace it represented. A huge crowd, stunned, stupefied, and at the same time still teeming with fear and anxiety, moved slowly toward the gates that had been constructed where the selection took place. Beside the gendarmes and SS men stood those in authority over these Jewish castaways: Schulz, the directors of other 'shops.' People went in blocks, according to their place of employment and residence.

Many still had bundles with them, food. The incorrigible property instinct! I saw terrifyingly horrific things there - above all the separation of children from their parents. One father of two children, a six-year old, and a baby a few months old, whose wife had long since been deported, had the way to life open before him, but without the children. He left them in the middle of the road and went to the gate. You should have heard the voice of his elder daughter: 'Daddy. I will not forget.'

Another woman who, despite permission for herself only to leave, wanted to smuggle out her little son. The German separated them and before the eyes of everyone began to beat her with his whip, kick her, punch her in the face and head. When he finally let her go and she came round, the child was gone. I saw her eyes, when she was looking around for the child. I wont forget. An old Jew, perhaps eighty years old, probably a grandfather, bowed to the SS man, who was a twenty-year old youth: he wanted to beg for the life of the boy he was leading. The German laughed. I wont forget.

The patients from the hospital were deported along with the medical personnel. Adina Blady- Szwajger, a doctor in the Bersohn and Bauman's Children's Hospital, which had been moved to Stawki Street, gave the children morphine, so that they could die in their beds and escape the horrors of deportation.

During this Aktion 2,648 people were shot, 54,269 were deported, 60 committed suicide, and 339 died a natural death. Many people remained in hiding during the Cauldron. The Germans went around and made random checks on houses that should have been abandoned. After this Aktion about 30,000 people remained in the ghetto legally, and there were about 25,000 -30,000 without numbers to live, in hiding, who were called ilegals or 'wild ones.'

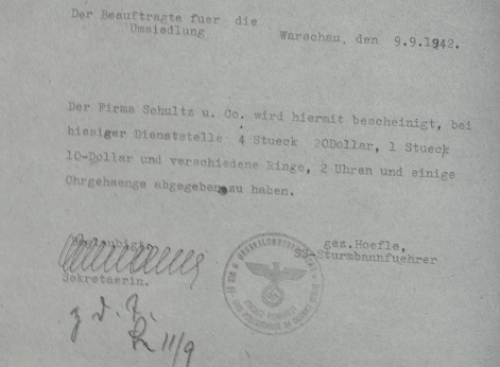

Document Signed by Hofle dated 9 September 1942 bearing the stamp Einsatz Reinhardt

Saturday September 12

Warm.

The funeral of Josef Kaplan in the cemetery in Okopowa Street

From this day on there were no more organized round-ups; the daily transports no longer left. People who had been taken by the Germans in the streets of the ghetto or on the other side of the wall were collected at the Umschlagplatz. Some would be taken to Treblinka and the rest were to be released at the beginning of October.

Tuesday September 15

During the night and morning it rained, but it cleared up later.

A selection in the Landau 'shop,' at 30 Gesia Street.

Wednesday September 16

The Polish underground press printed a declaration by the Directorate of Civil Resistance, that declared: 'Alongside the tragedy experienced by the Polish community, which has been decimated by the enemy, for nearly a year a monstrous planned slaughter of the Jews has been going on in our lands. This mass murder has no precedent in the history of the world, and all cruelties known from history pale into insignificance beside it. Babies, children, young people, adults, old people, cripples, the sick, the healthy, men, women, Jewish Catholics, Jews of the Mosaic faith, for no other reason than belonging to the Jewish race, are mercilessly murdered, poisoned with gas, buried alive, thrown out of windows into the street, before death experiencing the additional torture of slow dying, the hell of wandering homeless, torments, cynical torture by the executioners. The number of victims killed in this way is more than a million and is increasing daily. Being unable to oppose this actively, the Directorate of Civil Resistance in the name of the whole Polish community protests against the crime committed against the Jews. All Polish political and community groups join in this protest

Monday September 21

The ranks of the Jewish Order Service were reduced from 2,400 to 380 men. Police housing blocks in Ostrowska and Wolynska Streets were blockaded. Policemen escorted Lejkin and Szmerling to the Umschlagplatz.

On this day 2,196 people were deported

Thursday September 24

SS- Untersturmfuhrer Karl Brandt notified the Judenrat that the deportation Aktion in the Warsaw Ghetto was ended.

According to German sources, during the forty-six days of the Aktion 253,742 Jews were deported. According to Jewish sources, the population of the ghetto was reduced by more than 300,000 - including 10,300 who died or were killed in the ghetto, and 11,580 deported to the Dulag; about 8,000 people fled to the Aryan side.

Sources

Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2009

The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow, Elephant Paperbacks, Ivan R Dee publisher Chicago, 1999

Abraham Lewin, A Cup of Tears,Fontana Paperbacks, London 1990.

Helge Grabitz and Wolfgang Scheffler, Letzte Spuren, Hentrich, Berlin 1993

Photographs: Holocaust Historical Society, Bundesarchiv

Documents: Holocaust Historical Society, Hofle Document from Letzte Spuren

© Holocaust Historical Society, September 16, 2021