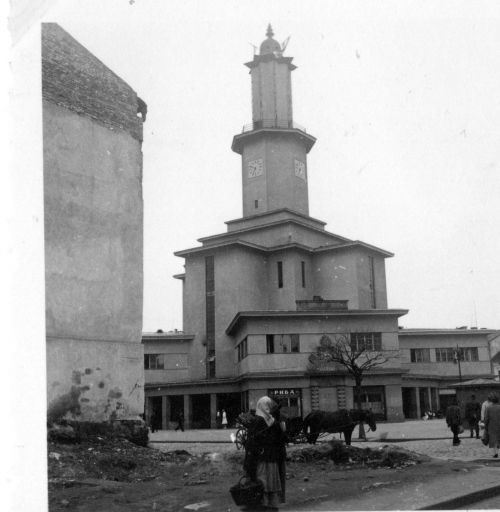

Stanislawow

Stanislawow - (Tall Trees Archive UK)

Stanislawow is located 70 miles south-southeast of Lvov. On the outbreak of the Second World War, approximately 25,000 Jews were living there, which comprised about one third of the population. On July 2, 1941, Hungarian troops occupied Stanislawow, but by the end of July 1941, the Germans had taken control of the city. At that time, SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Hans Kruger arrived to become head of the newly established Border Police Office (Grenzepolizeikommissariat) in Stanislawow. He brought with him Heinrich Schott, as his Jewish Affairs Officer (Judenreferent).

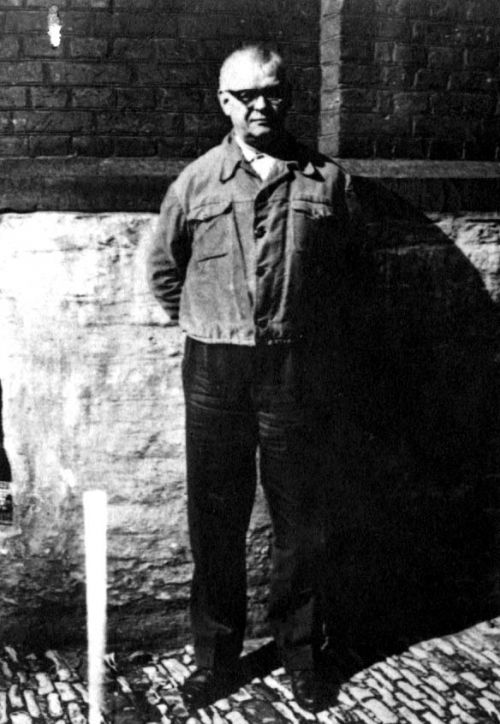

Hans Kruger (Yad Vashem)

The Kreishauptmann in Stanislawow from September 1941, was Heinz Albrecht. It is significant that all the key figures in the German administration in Stanislawow were radical anti-Semites. On July 26, 1941, on the orders of the Gestapo, a Jewish Council (Judenrat) was established to organise Jewish life and above all to implement German orders. The chairman was Israel Seibald, who had been active in the Jewish community before the war. His deputy was the lawyer Michael Lamm. The Jewish Council was ordered to establish a Jewish Order Police (Judischer Ordnungsdienst). In the early phases of the occupation the Polish and the Ukrainian conducted attacks against the Jews in the city.

On August 1, 1941, the Distrikt Galizien became the fifth district of the Generalgouvernement. One day later Hans Kruger ordered Seibald to draw up a list of Jews who belonged to independent professions, and these men were ordered to report to the Gestapo headquarters on Bilinski Street, where they were tortured, and most of them were killed. Anti-Jewish decrees soon followed: Jews had to wear armbands and perform forced labour. Soon the Judenrat instructed the lawyer Dr. Tenenbaum to set up a labour office, where registered Jews had to assemble to be assigned to various jobs for the Germans. Later, in the ghetto, it was this office that organised the Jewish work details that went outside the ghetto. The Germans also plundered Jewish property. In addition, the German civil administration, under Kreishauptmann Heinz Albrecht and Stadtkommissar Emil Beau, drew up plans to establish a ghetto.

Before the Jews were enclosed in a ghetto, the Germans wanted first to 'decimate' them. On October 12, 1941, they demonstrated how they meant to 'solve' the 'Jewish question' in the area. This day was later to be known as 'Bloody Sunday' (Blutsonntag). Unlike the other districts of the Generalgouvernement in the region of Stanislawow the local German administration did not wait until the extermination camps had been established. Thousands of Jews were gathered on the market square; then the German forces escorted them to the Jewish cemetery, where mass graves had been prepared. On the way, the German and Ukrainian escorts beat and tortured the Jews. At the cemetery, the Jews were compelled to surrender their valuables and show their papers. Some of them were then released, but the majority had to remain. The men of the Security Police (SIPO) then started the mass shootings, assisted by members of the German Order Police and also the Railroad Police. Hans Kruger personally took part in the shootings. The Germans ordered the Jews to undress in groups and then proceed to the graves, where they were shot. They fell into the graves or were ordered to jump in before being shot.

Some survivors have described the massacre in detail, revealing the incredible brutality employed by the German forces. Many survivors remember how bravely Dr. Tenenbaum of the Judenrat went to his death. Hans Kruger offered to set him free, but Dr. Tenenbaum said that he rejected this offer from a murderer and that he wanted to die with his brethren. In the evening, those Jews still alive were allowed to leave the cemetery. The German forces shot between 8,000 and 12,000 Jews on that day. Siebald, the chairman of the Judenrat, survived the massacre, but then went into hiding. His fate is unknown, but he was probably also killed later on. On the day after the bloodbath, Lamm was called to the Gestapo headquarters, where they informed him that he would be the new chairman of the Judenrat.

After the mass murder in the Jewish cemetery, the civil administration began preparing for the move of the remaining Jews into the designated ghetto area. The Judenrat succeeded in negotiating with the Germans regarding the inclusion of certain specific streets, but by the end of October, the final borders had been determined. As was the case almost everywhere in occupied Eastern Europe, in Stanislawow the Germans selected the oldest and most neglected part of the city to house the ghetto. Eventually, the boundaries of the ghetto were established as follows: Kazimierzowska St, the beginning of "Chavva", Roguski St., Sedelmajerowska, Kollontaj, Piotra Skargi, Minihinen, Halicka, Garbarska, Szewczenki, Szkolna, Kowalska, The River Bystrzyca, and back again to Kazimierzowska. Since some of the streets extended outside of the boundaries of the ghetto, or served as passageways, the ghetto was formed with a central area, and two or three separate areas, which were called isles.

The exact number of Jews incarcerated in the ghetto is not known, but an estimated 20,000 were crammed into this densely overcrowded area. Those Jews who lived outside the ghetto area were forced to move into the ghetto between the dates of December 1 and 15, 1941. Many Jews were unable to find housing and the Judenrat had to put them up in every available space, including storehouses, and synagogues. During the month of November, the 'Aryan' population living in this part of the city had to move out.

The ghetto was officially closed on December 20,1941, with a wooden fence separating it from the rest of the city. In the houses directly on the ghetto's perimeter, the windows had to be blocked with wooden bars. There were three gates, each guarded by German Schutzpolizei and the Ukrainian militia on the outside and by the Jewish Order Police on the inside. The commander of the Jewish Order Police was Zahler, a former sergeant in the Polish Army. Approximately 100 Jews served in the ghetto police.

Jews were permitted to leave the ghetto only to perform forced labour. There were several workshops, where Jews worked for the Germans. The Jewish Labour Office organised these workshops under its new chairman, Horowitz, who had succeeded Dr. Tenenbaum. The Labour Office issued identity cards to the workers. Many Jews worked outside the ghetto for various German institutions, at factories in the city, and also on farms. Salomon Guensberg recalled: 'The Jewish population carried out work under the most difficult of circumstances, virtually without any tools and they were beaten during the work.'

The living conditions in the ghetto were catastrophic. The sanitary conditions were dreadful; hunger and various diseases became permanent companions of the Jewish population. The official rations were far too small, more and more people died of hunger. The hospital was overcrowded. During the first winter in the ghetto, many people died of hunger and the cold. Only those with some money left were able to buy extra food on the black market, which had to be smuggled into the ghetto, but only a few people could afford the exorbitant prices demanded. It was possible to sell things legally to the non-Jewish population in a shop established and run by Eckhaus, a member of the Judenrat.

The Judenrat with Lamm at its head and Mordechai Goldstein as his deputy, tried to organise life and social welfare under these difficult conditions. Many different departments were established in the Judenrat, most of which were directed by Judenrat members. One of the most important departments was the Supply Division, which organised food supplies for the population. The Department of Food Procurement had to 'win the support' of members of the Gestapo and Schutzpolizei with bribes of money and other valuables. There was also a branch of the Jewish Social Self-Help (JSS) set up in Stanislawow, which received money every month from the headquarters of the JSS in Krakow. But all these efforts to support the numerous poor inmates of the ghetto remained inadequate. Living conditions in the overcrowded Stanislawow ghetto continued to decline.

By the end of March 1942, Hans Kruger told Lamm that only 8,000 Jews could remain in the ghetto and the rest, old, sick people and beggars would be taken to a labour camp. He ordered Lamm to hand over these Jews. When Lamm refused to comply, German police and Ukrainian militia surrounded the ghetto during the night of March 31, 1942. In a brutal 'Aktion' they expelled many Jews from their houses and drove them to Belwederska Street. Houses were set on fire to force Jews in hiding to come out. They had to march to the train station, where freight cars were already waiting and the people were deported to the Belzec Death Camp.

After these first deportations the ghetto was reduced in size, and the German authorities instructed the Labour Office to prepare new lists of those Jews who were able to work and those who were not. The Jews were divided into three categories:

A - Young and healthy Jews working in important factories or institutions

B- Jews able to work but without employment at the moment

C - Jews who were weak, old or sick

After this registration, thousands of Jews belonging to Category C were murdered, probably by shooting. Life became more and more unsafe and only Jews deemed fit to work were allowed to live in Stanislawow. The German police frequently searched the ghetto for Jews of Category B, who had not yet found employment. The civil authorities also began concentrating Jews from smaller communities such as Kalusz, Nadworna and Tlumacz into Stanislawow. Most of them were then murdered in successive 'Aktionen.' These killings were carried out in Rudolfsmuhle (Rudolf's Mill), a three -storey building that housed a grain mill. Here the Germans concentrated old and sick people, along with Jews that had been resettled from Ruthenia. The Germans also incarcerated there Jews with invalid work permits or those caught smuggling.

Living conditions were even worse than in the ghetto, Ukrainian policemen guarded the building on the outside, and the inside was guarded by members of the Jewish Order Service Police. Hans Kruger ordered all the sick Jews in the mill building to be killed. Owing to the dreadful living conditions in the building and the already failing health, most of the Jews soon fell ill. The mill directly under the control of Judenreferent Heinrich Schott, was a place of terror and mass murder. Schott personally took part in many of the shootings. Schutzpolizei Leutnant Ludwig Grimm often joined him in carrying out the shootings.

After the first mass resettlement 'Aktion' to Belzec death camp, Jews were regularly taken to the mill and shot there. Up to July 1942, most killings were carried out in the mill, and from August onwards in the courtyard of the SIPO headquarters. At this time the head of the Judenrat was Mordechai Goldstein, the former deputy head. It is not known exactly when Lamm was murdered and when Goldstein succeeded him, but Lamm was probably shot in a nearby forest together with other members of the Judenrat in June or July 1942.

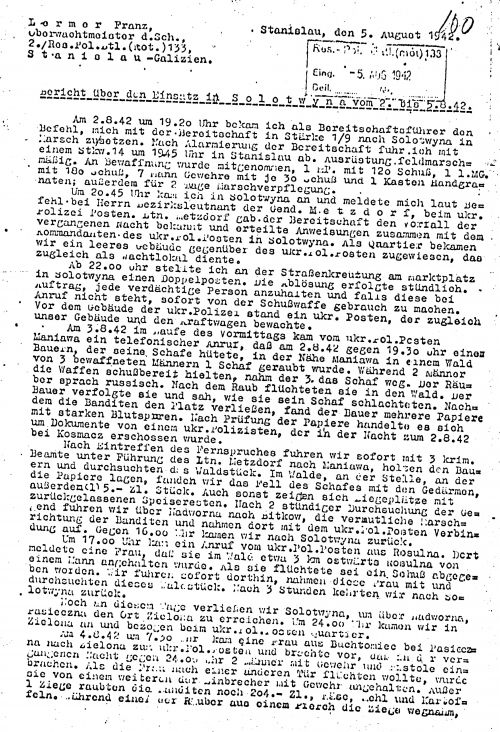

Police Report -5 August 1942 - Police Operation in Solotwyna

On August 22, 1942, the Germans also killed Mordechai Goldstein. He was hanged in public as the first symbolic victim during a reprisal 'Aktion.' The alleged reason for this reprisal was the murder of a Ukrainian, which the Germans blamed on a Jew. Schutzpolizei commander Walter Steege led this 'Aktion.' More than 1,000 Jews were shot. Some German policemen raped some Jewish girls and women before taking them to the courtyard of the SIPO headquarters. Steege also ordered the hanging of approximately 20 members of the Jewish Order Police. The Germans left the dead bodies hanging there for two days, as a warning to deter further resistance and to terrorise the Jewish population.

The next head of the Judenrat in Stanislawow was Schonfeld. According to the accounts of some survivors he apparently proved to be unscrupulous and a loyal servant of the Germans. He organised a new Jewish Order Service Police, of which he became its commander. Approximately 11,000 Jews were still living in Stanislawow, when the next resettlement 'Aktion' took place. On Rosh Hashanah, which fell on September 12, 1942, approximately 5,000 Jews were deported to Belzec death camp, where they perished.

On October 15, 1942, the Jewish population in Stanislawow was largely annihilated, only a few Jews who continued to work for various German institutions remained alive. By January 1943, Belzec death camp had ceased to receive transports, but the German police continued to carry out shootings of Jews.

During February 1943, Oskar Brandt, who had succeeded Hans Kruger in August 1942, ordered the police forces to surround the ghetto, thus initiating the final liquidation. People were brutally driven from their houses and marched to the Jewish cemetery, where they were shot to death by German policemen. Among the victims was Schonfeld, the head of the Judenrat. Many Jews had prepared hiding places, but owing to a lack of food and water, most of them emerged and were captured. Four days after the beginning of the 'Aktion,' the Germans put up posters announcing that Stanislawow was 'free of Jews' - Judenfrei. According to Jewish testimonies, approximately 500 Jews still remained in the city working for various German institutions, but these Jews were also shot gradually in turn. On June 25, 1943, most of the Jews still living 'legally' in Stanislawow were shot. Only a few professionals such as engineers, and technicians were still kept alive, incarcerated in the central prison.

When the Soviet Army reached Stanislawow on July 27, 1944, there were approximately 100 Jews in the city who had survived in hiding. In total approximately 1,500 Jews from Stanislawow survived the war.

A formal indictment against Hans Kruger was issued in October 1965, after six years of investigations by the Dortmund State Prosecutor's Office. On May 6, 1968, the Munster State Court sentenced Kruger to life imprisonment. He was released in 1986. In Vienna and Salzburg there were other trial proceedings against members of the Schutzpolizei and the Gestapo based in Stamislawow during the Second World War during 1966.

Sources

Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933- 1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Dr. Robin O'Neil, The Rabka Four, Spiderwize, London 2011

www. JewishGen

Photographs - Chris Webb Private Archive, Yad Vashem

Document - Tall Trees Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2019