Buchenwald

Buchenwald Crematorium 1945

The Buchenwald Concentration Camp was established at the beginning of July 1937, on the climatically harsh northern slope of the 478 meter-high Ettersberg, a hill, north of the city of Weimar. The camp was initially designed to hold up to 8,000 prisoners, mostly from central-Germany, and was to replace several camps such as Bad Sulza, Sachensburg and Lichtenburg, which were in the process of being dissolved. The immediate reason for the establishment of the camp, just north of Weimar, was the abundance of clay to be found in the area, which could be used for the manufacture of bricks.

The first prisoners arrived in Buchenwald on July 15, 1937. They were confronted with very difficult conditions: they had to clear the forest and construct the barracks and other buildings, without excavators, cranes, tip-carts, or tractors. These conditions together with the hopelessly inadequate rations, led to an enormous loss of life during the camp's construction.

Initially the camp was built on 104 hectares and this was later expanded to cover 190 hectares. It consisted of 33 wooden barracks, 15 two-storey stone buildings, a roll-call square, a prisoners infirmary, kitchen, laundry, canteen, storerooms, workshops for the camp's tradesmen, a disinfection building, market-garden and various other structures. Additional buildings, including a crematorium built in 1940, another disinfection building built in 1942-1943, and at the end of 1943, a railway station, as well as a brothel. This was the first concentration camp to establish a brothel, and approximately 16 female prisoners, most from Ravensbruck Concentration Camp, were forced to prostitute themselves for German and Austrian non-Jewish prisoners, and from 1944, onwards, for foreign prisoners, other than Soviets. The camp was secured by a double electrified barbed-wire fence, more than 3 meters high and by 22 two-level guard towers.

The camp administration and SS facilities were located outside the prisoners' area. These comprised of the command buildings, adjutant's offices, political department (Camp Gestapo) and the SS canteen, as well as administration and operational buildings, such as garages, barracks for the guards garrison, workshops, armoury, shooting range, central heating-station, stables, kennels, and indoor riding area. The SS - Totenkopfstandarte (Death's Head Regiment) 3 'Thüringen was stationed here. It was responsible for securing the camp. Some of the members of the Standarte were very young and were called up for frontline duty in September 1939. They were replaced by guards from the Concentration Camp Reserve, mostly older troops some of whom had been disabled in combat. At the beginning of 1944, more than 2,700 Luftwaffe members were transferred to Buchenwald to serve as guards. By the end of the camp's existence, they were divided into 46 companies each of 150 men and were responsible for guarding the main camp and the sub-camps. Buchenwald was also the central base for the Waffen-SS Driver Training and Replacement Unit. Furthermore, close to the camp were two settlements for the SS -Garrison and their families, including living quarters for the camp commandant Karl Koch, who held this post from July 1937, and December 1941, and his successor Hermann Pister, who was commandant from January 1942, until April 1945.

There were numerous prisoner work brigades incarcerated in Buchenwald Concentration Camp; prisoners were used to clear forests and to work in the quarry, they also worked in the brick mill that was established in Berlstedt, part of the German Earth and Stone Works (DEST) in 1938. They also served a number of local firms in the construction of the Marschler Settlement in Oberweimar and laid water pipes between Tonndorf and Buchenwald. The prisoners also worked in workshops operated by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Grossmarkethalle Weimar, and the prisoners built gas lines for the Weimar Stadtwerke. Altogether the prisoners worked at more than 90 locations for employers in Weimar and its surroundings. From 1940, onwards, there was a branch of the German Equipment Works (DAW) in the camp , where up to 1,400 prisoners worked in meeting SS war needs. During 1942, an armaments factory was established adjacent to the camp, which the SS leased in 1943, to the Weimar Wilhelm Gustloff NS Industriestifung. In 13 factory buildings, between 5,000 and 6,000 prisoners manufactured rifles and carbines, pistols, gun mounts, optical devices, and mechanical parts for the V-1 and V-2 rockets. The factory, secured by an electrified barbed-wire fence and 13 guard towers, was destroyed during an Allied bombing raid on August 24, 1944, and production ceased.

By 1940, construction of the camp was largely completed, during the early stages of the camp's existence German political prisoners formed one of the most powerful prisoner groups. They arrived with the first transports from Sachsenhausen, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg, which included leading Communists and other prominent personalities. In the autumn of 1938, leading Austrians arrived in Buchenwald, including senior officials from the Dolfuss and Schuschnigg governments. In the years that followed, several special prisons for prominent inmates were established close to the camp. French politicians were held in Falkenhof between 1943, and 1945; between 1942, and 1944 members of the Rumanian Iron Guard were held in the 'Sonderlager Fichtenhain.' Political prisoners and conspirators from the July 20, 1944, coup attempt on Adolf Hitler were held in isolation barracks. SS detention facilities in a cellar of one of the troop barracks held Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) 'special' prisoners from March 1945, onwards.

The camp was marked from the beginning by a bitter struggle between the criminal, the so-called 'green' prisoners - the colour of the triangle badge they wore and the 'red' prisoners the triangle badge that signified they were political prisoners, in respect of the positions in the camp's prisoner administration. By 1943, the Communist prisoners had control of all the important camp positions, including the Camp Elder and almost all the Block Elders, as well as foremen in the important work detachments. Organised along Stalinist lines, schooled in conspiratorial work, and with the benefit of intensive co-operation before their imprisonment in Buchenwald, the Communists, as one of the most stable groups in the camp, were able to build an administrative structure that, on the one hand, became indispensable for the SS, and on the other hand could lessen the SS terror. Eugen Kogon, an inmate of Buchenwald stated, 'What the Communists did in service of the concentration camp prisoners cannot be valued highly enough.' While this monopoly led to privileges held by specific prisoner groups, improved their chances of survival and resulted in the pragmatic exercise of power, it could not exclude some collaboration with the SS. There also existed, parallel to the prisoner administration, a secret organisation of mostly German Communists, who called themselves the 'International Camp Committee Buchenwald' (ILKB). The ILKB was the largest Communist underground organisation within the SS camp system, and it controlled and co-ordinated the prisoners' activities. This became obvious during the final years of the war, when the 100-strong Lagerschutz, the Camp Elder's mobile security force, became operational, including its own sanitation and rescue squads, as well as a fire brigade. At least to some extent, the Lagerschutz was able to limit the SS presence in the camp. But this group also served as a supplier for the planned armed uprising by the prisoners, which was to be accomplished on strict military lines, with the few weapons that had been smuggled into the camp.

There were not only Communists and criminals in the concentration camp; there were many other prisoner groups, which, included Jehovah's Witnesses, homosexuals, Sinti and Roma Gypsies, deserters, and others deemed 'unworthy of military service.' Buchenwald was, in its early phase, the only concentration camp to which the so-called 'work-shy' prisoners were sent. Beginning in 1938, and especially after Reich's Kristallnacht, Jews were sent to the camp. Between November 1938, and February 1939, approximately 10,000 so-called 'Aktionsjuden' were held in 'Pogromsonderlager,' a barn-like emergency accommodation without heating, windows or foundations. Many died from these inhuman conditions. A short-lived tent-camp was established in September 1939, at the edge of the roll-call square for 400 Jews from Vienna, 100 Polish Jews, and 100 non-Jewish Poles. By February 1940, more than 40 per cent of those inmates incarcerated there died.

In addition to these two temporary camps, there were other fenced-off special areas in the camp that served specific purposes. For example, between 1941, and 1945, three barracks held Soviet Prisoners of War (POW's) and several barracks functioned as a Labour Education Camp. With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, more prisoners from other countries were sent to Buchenwald, including Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Dutch, French, Spaniards, and Soviets. Other groups such as POW's, forced labourers and resistance fighters all swelled the ranks of inmates. Eventually there were prisoners from 35 different countries in the camp. The total population varied between the period of comparative normality, in which the camp held 8,000 to 10,000 inmates, to periods of catastrophic overcrowding. The high point was reached on April 6, 1945, when the camp held approximately 48,000 prisoners. The frequent overcrowding, coupled with inhuman work, horrific living conditions and the abysmal hygiene, resulted in epidemics, which at times spread to nearby villages.

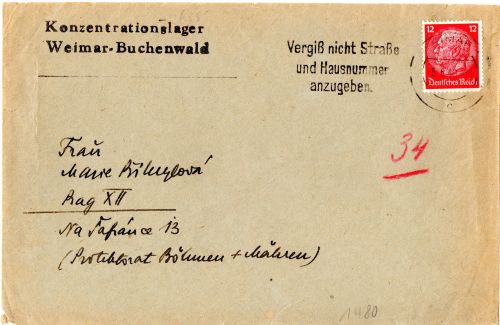

Buchenwald Concentration Camp - Letter Home to Prague (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Prisoners did not die just from the brutal work and poor living conditions. They were also murdered in cold blood. They were subjected to punishing roll-calls that lasted hours, hard labour during rest periods, food deprivation, and beatings, as well as labour in punishment companies, in the quarry and market gardens which resulted in physical injuries and exhaustion, which often proved deadly under the harsh conditions of the camp. In addition, the prisoners were sometimes physically mistreated, for example, by 'tree hangings.' Occasionally, prisoners were deliberately driven across the sentry line toward the camp fence, which resulted in the guards shooting them without warning. Buchenwald was the first concentration camp where a prisoner was hanged in public, during 1938, following an escape attempt in which an SS man was killed.

Prisoners were also killed on a much larger scale, for example, in 1940, Roma Gypsies from the Burgenland, who were suffering from an infectious eye disease were killed by injections. In the middle of 1941, the same fate met all those prisoners suffering from tuberculosis - some 500 or so victims. During 1941 -1942, as part of the 'Aktion 14F13' programme, at least six transports with 517 incurable or handicapped mostly Jewish prisoners were taken to the 'T4' euthanasia facilities at Bernburg, and Sonnenstein-Pirna and killed. The murder of prisoners who could no longer work reached its climax at the beginning of 1945, when completely exhausted prisoners from transports from Auschwitz and Gross Rosen Concentration Camps, were selected for lethal injections.

During 1943, some 8,000 Soviet Prisoners of War were killed in specially converted stables. They were shot in the neck by members of the so-called 'Kommando 99' while undergoing a fictitious medical examination. In the autumn of 1943, 36 Polish army officers were hanged, and a year later in autumn 1944, 38 members of the Allied secret services were murdered in the camp. These executions took place mostly in the crematorium and its courtyard. Buchenwald was also one of the execution sites for regional Gestapo offices. Civilians, prisoners, foreign forced labourers who had committed a 'crime' were executed in the camp. The most prominent victim of one such execution was Ernst Thalmann, chairman of the German Communist Party (KPD), since 1925. He had been interned since 1933, and he was murdered in the Buchenwald crematorium on August 18, 1944. Eugen Kogon estimated that the number executed in Buchenwald was approximately 1,100.

Medical experiments were also conducted in Buchenwald, and these activities also contributed to a number of deaths. Early in 1942, following discussions between government officials, Wehrmacht offices, representatives of the chemical industry, including IG Farben and Madaus AG, and the SS, Barracks 44, and 49 (later Barracks 46), were converted into laboratories, where the effectiveness of various vaccines were tested on prisoners. Initially confined to typhus, the tests were expanded to include yellow fever, small pox, typhoid, Para typhus A and B, cholera, diphtheria, various poisons, phosphorous rubber, and the effectiveness of blood plasma beyond its date of expiration. Block 50 was opened during 1943, by the Department of the Institute of Hygiene - Department for Typhus and Viral Research, as a production site for a typhus serum; medical practitioners from the Wehrmacht, the Robert -Koch Institute in Berlin, and a number of companies were able to work in the guest laboratory. Hundreds of prisoners died as a result of these experiments.

During 1942 and 1943, the transformation of the camp into a main and transit camp led to the establishment of the so-called 'Kleines Lager' - Small Camp. Here, on the one hand, newly arrived prisoners were held in quarantine. On the other hand, the 'Kleines Lager' served as a kind of waiting area for prisoners who had been selected for work in the sub-camps. The conditions in this camp, which was located in the northern area of the camp barracks, were even worse than in the main camp. This camp initially had 12, later 17, Wehrmacht stables, in each of which 1,000 to 1,500 people were accommodated in three and four -level bunks. Sometimes also army tents that became so completely overcrowded and offered little real protection from the elements. The 'Kleines Lager' was separated from the main camp by a double barbed-wire fence. Severe lack of food and catastrophic hygiene conditions, for example, there was only one mass latrine, turned the 'Kleines Lager' into a camp of death. This was especially so, from the beginning of 1945, when it started to receive transports from Auschwitz and Gross Rosen Concentration Camps, which were being evacuated due to the advancing Soviet forces. As Buchenwald was the largest concentration camp, it was expected to take these transports.

The SS -Garrison at Buchenwald included a number of notable SS -figures who went on to serve in a number of concentration camps and death camps during the Third Reich's reign of terror, and some who only served at Buchenwald. The following men along with the dates they served at Buchenwald and the other camps they served in, were as follows:

Dr. Erwin Ding-Schuler 1938, 1944

Dr. Waldemar Hoven - 1939 - 1940

Hermann Florstedt -1939 - Also served at Sachsenhausen and was Commandant at Lublin

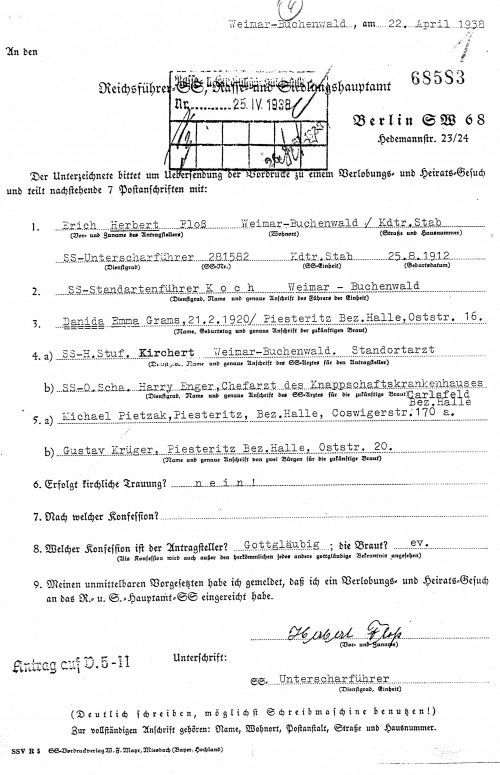

Erich Floss - 1938 -1939 - Also served in Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka

Kurt Franz - 1938 - Also served at Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor

Fritz Jirmann -1939 - Also served at Belzec

Karl Hoffmann -1942 -1943 - Also served at Oranienburg and Auschwitz

Franz -Xavier Maier - 1939 -1940 - Also served at Auschwitz

Arthur Rodl - 1937 -1940 - Also served as Commandant in Lichtenburg and Gross Rosen and at Sachsenburg

Dr. Gerhard Schiedlausky - 1943 - Also served at Dachau, Mauthausen, Ravensbruck, and Natzweiler

Hans Stark - 1937 - Also served at Dachau, Oranienburg, and Auschwitz

Arnold Strippel - 1937 -1941 - Also served at Natzweiler, Lublin, Herzogenbusch, and Neuengamme

Egon Zill - 1937 -1938 - Also served at Lichtenburg, Dachau, Ravensbruck, Natzweiler and Flossenburg

Erich Herbert Floss Document from his personnel file (Yad Vashem)

Within 100 days at the beginning of 1945, more than 5,200 prisoners died in Buchenwald, and from the week from February 26, to March 2, 1945, a further 3,096 prisoners died and most of these were incarcerated in the 'Kleines Lager'.' Even the prisoner administration was helpless in the face of these conditions. Nevertheless, Buchenwald remained until the end a place of self-assertion and resistance. For example, in the case of Evangelical Priest Paul Schneider, who continued to speak out against Hitler and Nazism, and preached the gospel from his prison cell. Paul Schneider was murdered in Buchenwald by a lethal injection on July 18, 1939, and the establishment in 1943, of national prisoner assistance committees that undertook measures to save the lives of children sent to the camp. On the initiative of the Camp Elder, two 'Kinderblocks' were established that held Jewish, Russian, and Ukrainian children, where they were educated in the so-called 'Poles' School. Nine hundred and four children survived Buchenwald; the youngest Stefan Jerzy Zweig, who was the son of a Polish -Jewish lawyer, was three and a half years old.

The evacuation of the prisoners to other camps such as Dachau, Flossenburg, and Theresienstadt was planned for the beginning of April 1945, but the Camp Elder's influence and the prisoners passive resistance resulted in the continued delay of evacuation transports, so much so, that of the 48,000 prisoners in the camp at this time, only 28,000 were evacuated, mostly Jews and Soviet Prisoners of War. It is estimated that about a third of the prisoners did not survive these death marches.

Buchenwald Concentration Camp was liberated on April 11, 1945, after approximately 2,700 of the 3,000 SS-men had fled the camp. Around mid-day, when an American Army tank was seen at the edge of the camp, the military-trained prisoners took action and occupied the camp's guard towers. They patrolled the area around the camp, where they were able to capture approximately 80 SS guards and make contact with the American forces. Care for nearly 21,000 prisoners who remained in the camp continued in the hands of the prisoner administration, even when the U.S. Army officially took over the camp on April 13, 1945, and disarmed the prisoners. In the following months, approximately a quarter of the 4,700 seriously ill prisoners died. In all, approximately 56,000 of the 238,980 male prisoners sent to Buchenwald died. At around 30 per cent, Jews were the largest group of victims in Buchenwald. The final group of prisoners left the camp in July 1945.

Representatives of the SS guards were tried before a U.S. Military Court after the war, in the so-called 'Buchenwald Trial' which was held at the former Dachau Concentration Camp between April 11, 1947, until August 14, 1947. Thirty members of the SS-Garrison were tried along with SS- Obergruppenführer Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck und Pyrmont, the Higher SS and Police Leader of Oberabschnitt Fulda -Werra, in which Buchenwald was located. Members of the SS-Garrison that stood trial included Camp Commandant Hermann Pister who was sentenced to death, but who died in prison. Members of the medical personnel were also put on trial, among them were Dr. Hannes Eisele, responsible for the murder of prisoners suffering from tuberculosis, physician August Bender. Other members of the SS-Garrison who faced justice were Hermann Hackmann, Max Schobert, and Ilse Koch, the wife of the former camp commandant SS-Standartenführer Karl Koch, who the SS arrested in December 1941, on suspicion of corruption and thanks to Heinrich Himmler's influence he was transferred to the post of first commandant at the Lublin Concentration Camp in Poland. He was removed from Lublin Concentration Camp for similar activities. He was sentenced to death by an SS and Police court and executed on April 26, 1945.

Returning to the 'Buchenwald Trial' which ended on August 14, 1947, and 22 death sentences were passed, as well as 5 life sentences, and 4 of the accused were given prison sentences of between 4 and 10 years. Twenty-five subsequent trials were held before the U.S. Military Courts at Dachau, and by 1951, a further 9 members of the Camp's Command and a Camp Elder had been executed. By the middle of the 1950's, all those previously convicted were free, except for Ilse Koch. Further court proceedings before German courts continued into the 1960's, for example against Martin Sommer and Ilse Koch at the Bayreuth Landgericht during 1958. Also former SS-Hauptscharführer Wilhelm Schafer, who had taken part in the murder of Soviet Prisoners of War.

Sources

Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933- 1945, USHMM, Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

French L. Maclean, The Camp Men, Schiffer Publishing Ltd 1991

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution, Vallentine Mitchell, London 1953

Wiener Library, London, UK

Tall Trees Archive, UK

Yad Vashem - Personal File Erich Floss

Photograph: Robin Cohen - Family Album, Chris Webb Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society, November 9, 2021