Ernst Röhm

Ernst Röhm standing to the left of Adolf Hitler (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Ernst Röhm was born in Munich on November 28, 1887, the son of an old Bavarian family of civil servants. Ernst Röhm was part of the last generation that sought to capture the values of the trenches, the camaraderie of the front-line soldiers in the First World War, with their restlessness, adventurism and latent criminality masquerading as nationalism.

Ernst Röhm was a fat, stocky, red-faced little man who had been wounded three times in the First World War, including having half his nose shot away, and when the Great War ended in 1918, Röhm became a professional freebooter and swashbuckler, with boundless contempt for the civilian way of life. His association with Adolf Hitler began in 1919, and they became close comrades - Röhm was one of the few people whom Hitler addressed as du in conversation. They marched together on the Feldherrnhalle on November 9, 1923, but the Beer Hall Putsch resulted in failure. The gun battle between the Nazis and the Bavarian State Police four policemen and fourteen marchers and two more members of the Nazi Party were killed. Hitler was arrested and sentenced to a term in Landsberg Prison.

Ernst Röhm was at this time a captain in the Reichswehr, and was active organiser of the NSDAP in Bavaria, and he was responsible for attracting many new recruits, and he became the keeper of a secret cache of weapons in Bavaria, which he hoped to use in a direct assault on the State. But the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch led to his dismissal from the Reichswehr and his temporary withdrawal from political life. Ernst Röhm was disorientated and he held a number of temporary jobs, which frustrated and bored him. He then set off for Bolivia, where he spent two years as an instructor in the military.

Ernst Röhm was recalled by Hitler after the spectacular electoral success of the Nazi Party of September 14, 1930, to take command of the SA, the Nazi para-military style force. Röhm rapidly expanded the SA into a popular army of street fighters, gangsters and toughs. From 70,000 in 1930, the SA increased to 170,000 in 1931, swelled by the growing number of unemployed and those in society who had fallen in status. Röhm regarded this plebeian army of desperado's as the core of the Nazi movement, the embodiment and guarantee of 'permanent revolution,' of the barracks socialism and blind dynamism he had absorbed during the First World War.

The SA fulfilled a crucial role in forging Hitler's rise to power between 1930, and 1933, by winning the battle of the streets against the Communists and by intimidating political opponents. By the end of 1933, however, the SA, which now numbered approximately four-and a half million men and was seemingly more powerful than the Reichswehr itself, had become disillusioned by the results of the Nazi 'revolution.' It felt cheated of the spoils of office, combined with the growing bureaucracy of the Nazi movement angered those like Röhm, who still dreamed of a Soldatenstaat - Soldiers State and the belief of the soldier over the politician. Röhm envisaged a coalition with Hitler as the political leader, with himself as the head of a vast armed force to be created by absorbing his SA force into the regular army.

As SA Chief of Staff, Reich Minister without Portfolio and Minister of the Bavarian State government, Röhm was still in a strong position at the end of 1933, but fatally misplayed his hand. Failing to understand Hitler's concept of a gradual revolution carried out under the cloak of legality. Röhm united opposition against Hitler's plans by his insistence on maintaining momentum in a socialist direction and talking openly about a revolutionary conquest of the State. His populist demagogy alienated the middle classes, the conservative Junckers and the Rhineland industrialists, whose support Hitler still needed.

Röhm's demands that the SA become a fully-fledged People's Army under his leadership particularly alarmed the Reichswehr generals, who were no less indispensable to Hitler's long-term plans. Moreover, Röhm had antagonised two dangerous rivals, Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler, to the point where they considered him Enemy Number One and were constantly putting pressure on Hitler to cut Röhm down to size, utilising the SS and Gestapo to this end.

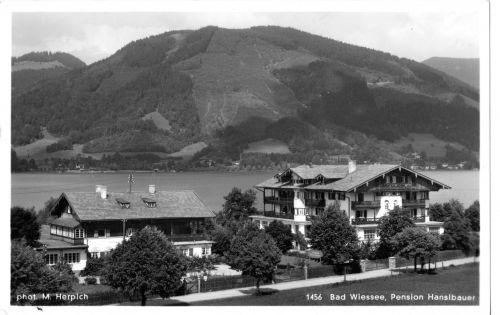

Röhm's own conduct and that of his entourage given to dissolute homosexual orgies and drinking bouts, loutish behaviour and wildly indiscreet remarks, made the task of his enemies easier. Nevertheless, Hitler hesitated to eliminate his oldest comrade-in-arms, a man to whom he felt a debt of gratitude and a certain warmth, even though he had become a liability and even a danger to his regime. After warning Röhm not to start a 'second revolution' and after ordering the SA to take a month's leave beginning in July 1934, the decision was taken to liquidate its leader and his closest followers. The guileless Röhm, who suspected nothing, was surprised on June 30, 1934, in a private hotel, the Pension Hanslbauer, at Bad Wiessee, a small Bavarian spa south of Munich, where he was taking a holiday with other SA leaders.

Bad Weissee - Pension Hanslbauer (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Röhm was awaken by Hitler and a detachment of SS troops and he was taken to Stadelheim Prison in Munich's Giesing district. Röhm was executed two days later, at midday on July 1, 1934, by SS- Gruppenfuhrer Theodor Eicke and his adjutant Michael Lippert, after refusing to take his own life. The Blood Purge, more famously known as the 'Night of the Long Knives,' led to the deaths of seventy-seven Nazis and at least one hundred others, including General Kurt von Schleicher, and his wife.

Röhm was posthumously branded a traitor and accused of hatching a nationwide plot to overthrow the government. The Nazi regime professed to be scandalised by the homosexual activities in Röhm's entourage, although this had been well known and tolerated for years. Röhm and his followers were charged with having wanted 'revolution for the sake of revolution,' an accusation which was closer to the real reason why he met his death. By the end of 1934, the SA had lost any political function in the new Nazi State and with Röhm gone, Hitler no longer had to choose between the nationalist and socialist wings of his movement.

Sources

R.S. Wistrich, Who’s Who in Nazi Germany, published by Routledge, London and New York 1995

Leaders and Personalities of the Third Reich by Charles Hamilton, published by R.James Bender Publishing. San Jose, USA 1984.

Photographs – Chris Webb (Private Archive)

© Holocaust Historical Society- October 18, 2019