Vilnius

Vilnius Occupied by German Forces (Bundesarchiv)

Vilnius is located 62 miles east-southeast of Kovno. On June 24, 1941, when German forces entered Vilnius, on June 24, 1941, approximately 60,000 Jews lived in the city. When the Germans invaded Lithuania on June 22, 1941, approximately 3,000 Jews fled the city, but at the same time a number of Jewish refugees from Western Lithuania arrived in Vilnius. The first German Security Police detachment to arrive in Vilnius was Einsatzkommando 9, and in July 1941, this unit, together with the Lithuanian 'Ypatingas Burys' (special troops), murdered approximately 10, 000 Jews near the Ponary railroad station, which is located some 6 miles south of Vilnius on the road to Grodno.

The Germans ordered the establishment of a 10-member Jewish Council (Judenrat) on July 4, 1941. By the end of the month it had been expanded to 24 members, and Shaul Trotski, was appointed as its head. Within a few days, rumours of the massacres carried out at Ponary reached the Judenrat. At the start of August 1941, a German civilian administration took over from the military in Vilnius. The city's Stadtkommissar was Hans Hingst, and the Gebietskommissar for the surrounding rural region, the so-called 'Wilna-Land' was SS-

On the orders of the German authorities, the Lithuanian officials and police forces imposed restrictions on the Jews, including markings and a curfew, whilst some Germans stole Jewish money and property. In August 1941, Einsatzkommando 3 took over responsibilities for Vilnius. A report produced by its commander SS-

Under the new civil administration, Generalkommissar Theodor Adrian von Renteln ordered Hingst to establish a ghetto. Hingst selected the old part of the city from among several Lithuanian proposals, as most of the Jewish population lived there. The ghetto was established in early September 1941, under the control of Hingst, together with the Lithuanian authorities serving under him, with Franz Murer also playing a key role in its administration. The German Security Police, subordinated to Einstazgruppen 3 in Kaunas, handled security; they assigned the 'Ypatingas Burys' to guard the ghetto perimeter and to conduct mass killings.

The resettlement of the Jews into the ghetto took place on September 6 -7, 1941, when Lithuanian policemen drove the Jews out of their homes, and Lithuanian Self-Defence officials forced them into the designated ghetto areas. The sick and those unable to walk were left in their homes temporarily. Some 40,000 Jews were crowded into two separate ghetto's, whose combined area had previously housed only about 4,000 people. The small ghetto included Jatkowa, Zydowska and parts of Gaon and Glezer Streets. The large ghetto included Oszmianska, Dzisnienski, Jatkowa, Zmundzka, Rudnicka, Szpitalna, and Straszun Streets. At this time the Judenrat was liquidated, and separate Jewish Councils were created for the two ghetto areas. Overcrowding was extreme. Several families had to share a single room, and each person was allotted only 1 to 2 square meters. Some of the buildings in the ghettos were not connected to the local sewage system. Initially, there was only one public bath, but a second opened later. However, there use by so many people may have contributed to the spread of infectious diseases. A hospital with more than 150 staff treated some 3,000 patients during 1942.

A report by the Judenrat from October 1941, stated that the daily ration for each ghetto inmate was 100 grams of potatoes, 50 grams of cabbage, 30 grams of carrots, and 20 grams of turnips - produce that normally used to feed cattle. On April 9, 1942, the Generalkommissar issued the following regulations: non-working Jews would receive half the rations issued to the local population; working Jews would receive a full bread ration and Jewish workers essential for the war effort would receive full rations, equal to the local population.

The ghetto exits were sealed with barbed-wire, and windows and doors along the ghetto boundary were barricaded, and the telephone lines were cut. For each ghetto there was only one gate, located in the large ghetto on Rudnicka Street. The ghetto was guarded internally by approximately 200 Jewish policemen, under the command of Jacob Gens. At the beginning, Lithuanian auxiliaries guarded the exterior of the ghetto. In August 1943, external security was maintained by German police troops.

Jews under guard in the Vilnius ghetto (Bundesarchiv)

After the sealing of the ghetto in September 1941, the number of its inhabitants was reduced dramatically by a series of brutal mass killings. They took place several times a week, with approximately 1,000 victims on each occasion, mostly of people unable to work. During September 1941, most of those not registered for work were transferred to the smaller ghetto, known as Ghetto No. 2. On October 1, 1941, on Yom Kippur, the Germans conducted a large 'Aktion' during which several thousand Jews were taken to Ponary and shot. In mid-October 1941, Ghetto No. 2 was completely liquidated, and the remaining 6,000 to 8,000 Jews were herded to Ponary and shot. Through the end of October, approximately 5,000 to 7,000 Jews were killed in the first 'yellow certificate Aktion,' and approximately 2,000 more Jews were killed in the second 'yellow certificate Aktion,' in early November 1941, as the ghetto was brutally searched for any Jews in hiding. During the next 'aktion' which took place at the end of November/ early December 1941, 200 ghetto inmates were executed, and during the 'pink certificate Aktion' on December 20 -21, 1941, approximately 400 more Jews were killed. At this time, some Jews in hiding physically resisted efforts to extract them.

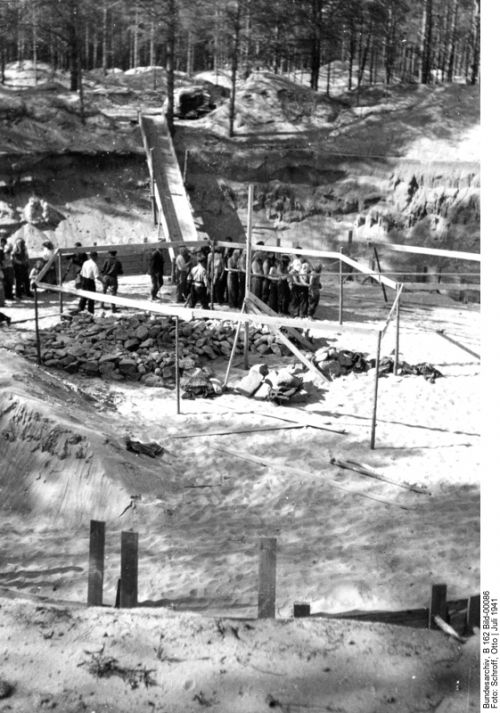

Ponary - Mass Executions Site (Bundesarchiv)

After December 1941, the situation in the Vilnius ghetto became relatively stable for about a year and a half, until the events leading up to the ghetto's liquidation in September 1943. In February 1942, there were approximately 17,200 Jews in the ghetto, some 14,200 that were classed as 'legals,' who received bread rations, and about 3,000 who were classed as 'illegals,' who the vast majority moved into the 'legals' classification during 1942. Still, repressive 'Aktions' continued on and off. The reasons for arrest included illegal acquisition of food, use of false documents, illegal trade, planned escapes from the ghetto or the workplace, staying outside of the ghetto, and ownership of valuables. In most cases, the punishment was execution, described in relevant documents as 'dealt with according to orders,' or 'liquidated.'

On September 30, 1941, Hingst ordered that wages for male Jews, aged between 16 and 60, should be 0.20 Reichsmark (RM) per hour; for female Jews, 0.15 RM per hour; and for younger workers under 16, 0.10 RM per hour. The wages increased in June 1942. These rates applied only to private companies. The German local employers, military employers and the city of Vilnius paid only half of these amounts, as they had to transfer the other half to the city authorities. If the employer provided the working Jews with a warm soup, he could deduct 0.30 RM from their daily wages. Jewish workers could only be hired through the Labour Administration in Vilnius. The police station in charge of the ghetto controlled the Jews leaving the ghetto. Only Jews assigned by the Labour Administration with a corresponding pass could leave the ghetto in groups, under escort for their workplaces. Jews could not buy food or wood and take them into the ghetto. Deliveries of these goods were organised by grocery companies and the city administration.

The places that employed Jews in Vilnius included the Kailis factory, which made fur products; workshop for cars; a Jewish labour camp on Antakolsku Street; and another Jewish labour camp whose inmates worked for the German Security Police. Outside of Vilnius, Jews were used to dig peat, especially in the areas of Biala Waka, Bezdany, Rzeszy, Podbrodzie, Nowa Wilejka and Ignalino. One of the largest outside labour sites was the Giesler Company camp, which built and repaired railroad tracks for the Wehrmacht.

During April 1942, a theatre opened in the ghetto and also there was an orchestra, a music school and two choirs established. A public library contained approximately 45,000 books, many of them in Polish. A number of sporting events were also organised. These activities gave the Jews of Vilnius, the opportunity to free themselves from the pressures of ghetto life for a few hours and represented a form of passive resistance to Nazi oppression. Three synagogues served the needs of the faithful inside the ghetto.

In July 1942, the Judenrat was dissolved and Jacob Gens was appointed head of the ghetto, while still remaining chief of the Jewish Police. On July 12, 1942, Gens announced, 'The basis of the ghetto is work, discipline and order. Every resident of the ghetto who is capable of work is a pillar on which our existence rests.' Thus Gens pursued a strategy of survival through labour, trying to make the Jews useful to the Germans. The ghetto administration included departments for police, labour, industry, supply of food, health, housing, social welfare and also culture.

In the autumn of 1942, the ghetto administration under Gens assumed responsibility for the remaining small ghettos to the east in Gebiet Wilna -Land. Over the following weeks these ghettos were consolidated, with some Jews being transferred to labour camps, whilst others were simply put to death. During the final liquidation of these ghettos in late March / early April 1943, some Jews were sent to nearby labour camps and others to the Vilnius ghetto. Some 4,000 were shot and killed, and these 'aktions' by the Germans severely undermined morale in the Vilnius ghetto, as this demonstrated that Gens was powerless.

Between January 1942, and September 1943, Zionists, Bundists and Communists came together to plan armed resistance in the Fareynikt Partizaner Organizatsye (FPO). The leader of this group was the Communist Yitzhak Witenberg. For a brief period of time, another smaller armed group under the leadership of 'Jechiel' was active, and during 1943, managed to establish contact with the FPO. The FPO was in contact with the Jewish Police, as Joseph Glazman had a senior position in both organisations. However, in the spring of 1943, when relations between the German authorities and the Jews deteriorated markedly, the FPO demanded armed resistance. Gens, aware that resistance would threaten the very existence of the ghetto, increasingly acted against the FPO's plans, although he allowed for some resistance fighters to leave for the forests.

In July 1943, after the capture of two non-Jewish Communists who had contacts with the FPO, the Germans demanded that Gens hand over Witenberg, believing he was part of the city's Communist resistance movement. Witenberg was briefly arrested but then escaped with the aid of FPO fighters. Gens then spread word that the Germans would destroy the ghetto if Witenberg did not surrender. Eventually, on July 16, 1943, Witenberg surrendered voluntarily but he committed suicide in prison. Abba Kovner then took over the leadership of the FPO. After this crisis, some members of the FPO decided to escape to the nearby forests to join up with Soviet partisan units. One group, including Joseph Glazman, was ambushed on the way to the forest, and most were killed. The Germans then conducted severe reprisals, killing the family members of those that had fled the ghetto.

Following RFSS Heinrich Himmler's order of June 21, 1943, for the transformation of remaining ghettos into concentration camps, there was a further intensification of anti-Jewish policy in the Vilnius region. The Security Police dissolved five labour camps over the following weeks, murdering most of the inmates, as they feared these Jews would flee to join the Soviet partisans. Then in August 1943, a series of deportations to Estonia commenced, which spread alarm among the Jews and further undermined trust among the Jews in Gen's leadership. In total, according to German figures, 7,126 Jews were sent to Estonian concentration camps, to work in the extraction of oil shale. There were four deportation 'aktions' on August 6, and August 24, and on September 2 and 4, 1943. From early September 1943, the ghetto was sealed off, and even the Wehrmacht was denied access. No additional food entered the ghetto and prices rose immediately. Gens ordered a new registration on September 6, 1943, which recorded 9,637 Jews - made up of 2,157 men, 5,827 women, and 1,653 children.

In mid-September 1943, SS-

The main HKP 562 works, with its large vehicle repair workshops and its spare parts department, as well as the HKP headquarters were located in the eastern outskirts of Vilnius. The HKP also supervised sixteen other vehicle workshops. The HKP headquarters was located on Olandu Street, opposite the entrance to the main HKP workshops. The HKP 'Panzerkaserne' workshops were located on Valkowsky Street. A third large workshop was at the former bus depot on Legionowa Street. The Jewish workers of the HKP were housed in two pre-war blocks of the Jewish -French Philanthropist Society built in 1904, which was located on Subocz Street, some 1.3 km from the HKP headquarters and workshops. In September 1943, just before the liquidation of the Vilnius ghetto, Major Karl Plagge, in charge of the workshops, managed to evacuate over 1,000 of the HKP workshops and their families from the ghetto to hastily installed workshops in these two blocks. There, the 'Plagge-Jews' remained in relative safety for the time being.

As well as sending Jews to the HKP, another 1,500 Jews were sent to the Kailis fur factory. Dozens of people were sent to work for the Security Police and at the military hospital. During the 'aktion' between September 22 and 24, 1943, Lithuanian, Ukrainian and other auxiliary police units took part. Approximately 1,600 Jewish men were deported to Estonia, and between 1,400 and 1,700 Jewish women were sent to the Kaiserwald Concentration Camp near Riga. More than 3,000 people were killed, either in the ghetto or by shooting in Ponary. The search for Jews in hiding continued for a number of days. Several thousand Jews remained at the various work sites, that now became labour camps.

In the period between July 2, 1944, and July 7, 1944, the camps and workshops at the HKP, the fur factory, the Security Police, and the hospital were liquidated. In the case of the HKP workshops, the day before on July 1, 1944, as the Red Army approached Vilnius, Karl Plagge came into the camp and warned the Jews that he was no longer in charge of the camp and gave the Jews the covert warning that the SS killing squads were coming to the HKP camp the next day. The HKP 562 unit left for Kovno in the night of July 2, 1944. The Jews working for the Security Police, together with their families, were transferred to Fort IX in Kovno and shot.

Vilna was liberated by the Red Army on July 13, 1944, but only between 2,000 and 3,000 of the original Jewish inhabitants of Vilnius lived to see the day. They either hid with the partisans in the forests, or worked in camps in Germany or Estonia, this small figure of survivors equated to a mortality rate of approximately 95 per-cent.

The fates of the Nazis that had persecuted the Vilnius ghetto, and their collaborators were mostly long prison sentences following war crimes trials. One of the main perpetrators was SS-

Franz Murer was handed over to the Soviet authorities by the British after the war and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He was released, however, in 1955, and repatriated to Austria, in connection with the Austrian State Treaty. Simon Wiesenthal subsequently undertook efforts that resulted in another trial in Austria during the 1960's. Murer was initially acquitted, and despite a reversal by the Supreme Court in 1963, no further punishment was handed out.

The courts and tribunals of the Lithuanian SSR charged a number of people with participation in mass murder at Ponary. Among the accused were the following members of the Lithuanian special unit, 'Ypatingas Burys' who were sentenced to death on January 29, 1945: Juozas Augustas, Borisas Baltutis, Mikas Bogotkevicius, Jonas Divilatis, Jonas Macis, Vladislava Mandeika, Jonas Ozelis, Kozlovskji, Stasys Ukrinas, and Povilas Vaitulionis. Julius Rackauskas was sentenced to 25 years in prison on March 15, 1950.

The following persons were sentenced by Polish courts for participation in the mass killings at Ponary: Witold Gliwinski, Jozef Miakisz, Wladyslaw Butkun, and Jan Borkowski.

Sources

Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933- 1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

French L. Maclean, The Camp Men, Schiffer Publishing Ltd 1991

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution, Vallentine Mitchell, London 1953

Wiener Library, London, UK

Photographs -Bundesarchiv

© Holocaust Historical Society 2017