Radzyn

Radzyn - A member of Polizei Battalion 43 (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Radzyn Podlaski is located 43 miles north of Lublin. During the 1930's, the general economic crisis was accompanied by an anti-Semitic boycott of Jewish trades and crafts. On the eve of the Second World War, approximately 3,000 Jews were living in Radzyn. At the start of the Second World War, it was unclear whether the area would be under Soviet occupation, but by mid-October 1939, the Germans had taken control of Radzyn. Many of the younger Jews fled eastward.

During the first weeks of the German occupation the Jewish population of the town was confronted with violence and plundering. Germans visited Jewish houses and as Nuchim Perelman recalled beat the inhabitants, ordering the women to undress and dance on the tables. They plundered valuables.

The centre of the town was used for housing soldiers; the two great synagogues served as stables for horses. As Joseph Schupack recalled:

'The furnishings of the synagogues had been desecrated and demolished beforehand. Every new unit that marched into town seemed obligated to vandalise and destroy. After demanding contributions, seizing hostages and plundering Jewish stores, the German occupation troops established themselves. The German authorities tightened the screws on us Jews increasingly tighter. Many Jews with beards wore bandages on their faces pretending to be wounded already.'

On December 6, 1939, a great part of the Jewish population of Radzyn was driven from the town, but they returned the following April from the village of Slawatycze on the River Bug. A Jewish Council (Judenrat) was established, consisting of 12 members, with David Lichtenstein, a well-known and respected person in the town as Chairman. The Judenrat had to organise Jewish life in the town, including being responsible for sending Jews to different kinds of forced labour projects. Shimon Kleinboim, a former representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) in Poland, became responsible for matters of Welfare.

There were periods of calm when life began to normalise, but increasing restrictions made Jewish life in Radzyn more difficult. The removal of Jews from the economy left most of them without any means of subsistence.

Radzyn was the capital of Kreis Radzyn, so the Kreishauptmann resided there: from October 1939 to August 1940, this was Hennig von Winterfeld; from August 1940 to October 1941, Dr. Fritz Schmiege; and after that until July 1944, Ludwig Stitzinger. The chief of the Gestapo in Radzyn was a man named Fritz Fischer. In the building of the former municipality there was a new prison that became infamous for the murder and torture of prisoners.

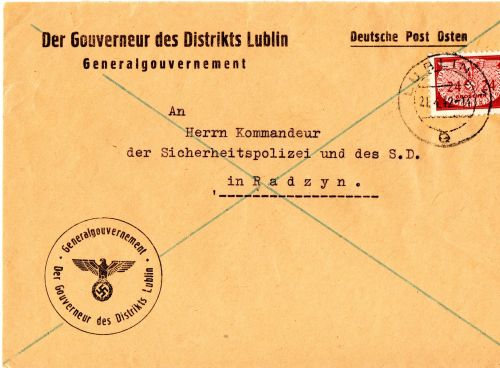

Letter from Lublin to the Commander of the SIPO and SD in Radzyn (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Although there was no sealed-off ghetto, the Jews were driven out of their homes in the better parts of town and around the market place, and a Jewish quarter was established during 1940, in one of the most run-down areas, where before the Second World War the poorest element of the Jewish population had lived. It consisted of Kozia, Szkolna, Kalen, and several smaller streets. When those Jews who had been driven out of the town in December 1939, returned in the spring of 1940, some of them had lost their homes, as they were not in the designated area. This was recalled by Yehoshua Ron:

'My father hired a peasant wagon and traveled from Slawatycze to Radzyn and back to us. He returned on a frosty and snowy evening with the unhappy news. The head of the Judenrat who had been appointed in Radzyn in the meantime was not too enthusiastic to take us back. The house we had built, so he claimed, the house we had initiated on Passover in 1939, was outside the confines of the ghetto.'

As Joseph Schupack recalled: 'Although Radzyn was not a fenced-in ghetto with barbed wire, hardly anyone dared to leave the Jewish section. Venturing outside always brought trouble, risks and even danger to one's life.' The Kreishauptmann reported in September 1941, that there were no sealed-off ghettos in the whole of the Kreis, only Jewish quarters, but that some Jews were still living outside of these quarters due to the lack of living space inside. But even if there was no sealed-off Jewish quarters in Distrikt Lublin from February 1941, Jews were no longer allowed to leave their places of residence, and from October 1941, the punishment for leaving the town without official permission was the death penalty.

The process of ghettoisation in Radzyn does not appear to have been completed until the spring of 1942. According to an article titled 'Ghetto in Radzyn' published in the regional newspaper, Nowy Glos Lubelski, in mid-April 1942: 'in the last weeks, a special Jewish quarter was created in Radzyn, into which all Jews, who still live beyond it, soon will be moved.' Among the motivations for the German authorities was the effort to reduce black market activity, which was blamed on 'corrupt Jews.'

Regarding the reaction of the local Polish population, there are hardly any documents on Radzyn itself. As Joseph Schupack recalled, there were some Poles who wanted to help, but many of them just wanted to get their hands on Jewish possessions, and therefore they offered to look after such items until the end of the occupation.

Able-bodied Jews had to work for the Germans. The workers met early in the morning in front of the Judenrat building on Kozia Street and were escorted from there to their places of work. The Judenrat tried to organise this work as effectively as possible to prevent German terror. Some Jews were forced to work; others were very poor and tried to find work to have something to eat. The German employment office in Radzyn assigned Jews of the entire Kreis to various workplaces, among the most important was the Water Regulation Authority (Wasserwirtschaftinspektion) in Biala Podlaska. From the autumn of 1940, among the most important workplaces were the construction sites of military airfields, the employment office had to request Jewish workers from Lublin, as there were not enough workers in Radzyn.

In Radzyn there was a group of young members of Ha-Shomer Ha-Zair and other Zionist organisations who met regularly and were in contact with Jews from surrounding towns such as Miedzyrzec Podlaski. The main task was organising escapes, and some Jews fled from Radzyn to the surrounding forests, trying to reach partisan groups. Some Jews from Radzyn were active in partisan groups later on. One of the people supporting these escapes was Rabbi Shmuel Leiner. After he had been betrayed in June 1942, the Gestapo arrested him and he was executed in front of the synagogue. In his poem, ' The Song about the Radzyner,' the well-know Jewish writer Yitzchak Katzenelson, commemorated this event.

In August 1942, approximately 6,000 Jews were living in Radzyn. The first deportation to the Treblinka death camp took place on August 20, 1942.A few months later on October 1, 1942, Some 4,000 Jews were deported either directly to the Treblinka death camp or to the ghetto in Miedzyrzec Podlaski, which functioned as a collection point, from which the transports to the death camps were organised.

On October 1, 1942, the Germans deported 2,000 Jews from Radzyn directly to Treblinka death camp. The final liquidation of the Jewish quarter was carried out between October 14 and 16, when the remaining Jews were sent to Miedzyrzec Podlaski, and from there on October 27, 1942, they were deported to Treblinka where they were murdered in the gas chambers.

Joseph Schupack described the final deportation from Radzyn:

'The ones who were driven together at the collection place were encircled by the SS and Police. Older people who could not walk were shot on the spot. Screaming women were beaten with rifle butts, and some children standing in the way were shot. Only a few Jews had suitcases, blankets, or coats. Watching the moving lips of some, one knew that they were reciting their last prayer..... That day marked the end of the Jews of Radzyn.

Sources

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012.

Jewish Gen online resource

Photograph: Chris Webb Private Archive

Envelope: Chris Webb Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society, July 14, 2020