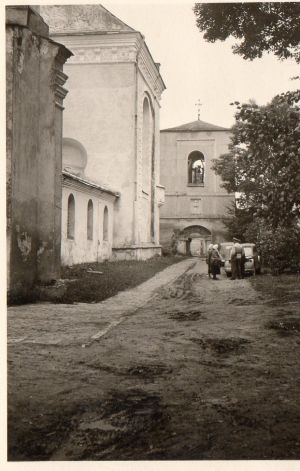

Sokal

Sokal Ghetto

Sokal is a town located on the banks of the River Bug, some fifty miles from Lvov, in the Ukraine. In the 1930’s approximately 5,200 Jews lived in Sokal, representing about half of the town’s population. In addition to merchants and artisans, the Jews of Sokal counted members of the liberal professions and owners of factories that engaged in light industry. Sokal had a merchant bank of the Jewish merchants’ union and a number of welfare societies. Hasidism was very strong in the town, and Agudath Israel was active there, in addition to several Zionist movements and the Bund. The various parties ran youth movements and cultural clubs. Sokal had traditional Hadarim, a Beit Yaakov school for girls, and a Tarbut Hebrew school. In September 1939, Sokal was inundated with hundreds of Jewish refugees who thronged to the town from western Poland, and the local Jews established a council to assist them. The Red Army entered Sokal in the second half of September 1939. Under Soviet rule, the factories were nationalised, commerce was significantly cut back, and Jewish parties were abolished. In the summer of 1940, a few middle-class families along with some of the refugees that refused to accept Soviet citizenship were deported to the interior of the Soviet Union.

On 23 June 1941, the Germans occupied Sokal, in the initial onslaught of Operation Barbarossa and murdered eight Jews. Five days later on the initiative of SS- StandartenIn July 1941, the Germans established a seven-member Judenrat headed by G. Yanoshcinski that was ordered to supply hundreds of Jews daily for forced labour. In November 1941, all the Jewish men aged fourteen to sixty were registered in the German employment bureau. Those who were employed in jobs deemed vital to the German war effort received special work permits. On 27 December 1941, the Jews were ordered to hand over all furs in their possession to the Germans. That same winter, the community suffered from a severe shortage of food and many people died of starvation. The Judenrat established a public soup kitchen that distributed hundreds of portions of soup each day.

In February 1942, the Germans demanded that the Judenrat hand over 500 people from Sokal and its environs for forced labour. A bribe reduced the quota to 200 Jews and in March 1942 another 450 Jews were deported to labour camps. The Judenrat and their family members sent the workers packages of food and clothing, but in most cases the packages did not reach their intended destinations and by the summer of 1942, all contact was lost with the workers and it is assumed the vast majority of these men perished.

On 17 September 1942, a mass ‘Aktion’ was carried out in Sokal. German and Ukrainian police blocked all entrances to the town, combed through the Jewish homes, took all the Jews they found to the marketplace, where they killed some 160 of them, and the rest numbering some 2,000 were deported to the Belzec death camp, where they were murdered in the gas chambers. On 15 October 1942, one month after the ‘Aktion,’ the Jews were concentrated into a ghetto. On 22-24 October 1942, the Germans transferred about 3,000 additional Jews to Sokal from surrounding localities, including Radziechow and Mosty Wielkie. In all more than 5,000 people were packed into the ghetto, in a state of extreme overcrowding; they only had four wells from which to draw water and it should come as no surprise that a typhus epidemic broke out, killing more than twenty people a day. The Judenrat established a hospital and clinic, to help improve the health of the ghetto’s residents.

Two weeks after the establishment of the ghetto, on 28 November 1942, a second ‘Aktion’ was carried out during which about 2,500 Jews were deported to Belzec death camp. Most of the Jews who jumped off the cattle cars were killed by the jump or shot by the guards. G. Yanoshcinski, the Judenrat head attempted to escape from the ghetto and was murdered. After the second ‘Aktion,’ the Germans appointed David Kindler as head of the Judenrat, though he refused and the Germans killed him, and they appointed the engineer Schwartz.

After the two ‘Aktions,’ attempts to escape from the ghetto to the forests and to Christian friends increased, but these attempts were hindered by a combination of an indifferent local population and searches by Germans, and gangs of Ukrainian ultra-nationalists led by Stefan Bandera, that roamed the forests killing Jews. In the ghetto itself, poor sanitary conditions continued to take a heavy toll on the Jews. Some 1,500 people are estimated to have perished from hunger and disease in the ghetto during the winter of 1942 -1943.

In the spring of 1943, groups of Jews that were living in the forests began to emerge from their hiding places and return to the Sokal ghetto, responding to German promises that they would be employed in factories. But this proved to be a false dawn, on 27 May 1943, an ‘Aktion’ to finally liquidate the ghetto was carried out. During this ‘Aktion’ there were attempts to organize a mass escape, but most of those fleeing were shot on the spot and buried in the local cemetery. The rest of the town’s Jews were led to pits located about three kilometers from Sokal and shot to death.

Sources:

The Yad Vashem Encylopiedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust Volume 1, Yad Vashem, 2009.

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Photograph - Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2014