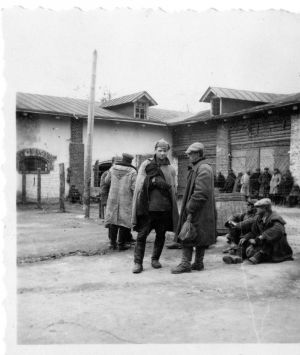

Riga Ghetto

Riga - Prisoners captured by the Germans

Riga, the capital of Latvia is located 296 miles north-northwest of Minsk. In 1935, the Jewish population of Riga was 43,672, which amounted to circa 11% of the total population. On 1 July 1941, German troops reached the Riga, accompanied by elements of Einsatzgruppe A,under the command of SS Brigadeführer Walther Stahlecker. The occupying authorities started to discuss the creation of a Jewish ghetto the same month.

Although the concentration of Jews in ghettos was in line with the general guidelines on the treatment of Jews, a shortage of labour was the main reason for the creation of the ghetto. The first documented mention of a ghetto in Riga is contained in an internal letter of the Labour Section of the Army Economic Department, dated 21 July 1941. This noted that discussions between the German Army and the Security Police (SD) had already taken place. The decision to establish a ghetto in Riga came quickly, and all the agreed parties – the Wehrmacht, the Security Police, and the civil administration - agreed on the need to concentrate and isolate the Jewish population. At the beginning of August 1941, the German Security Police designated the residential area of Riga that was to become the ghetto. It consisted of a working-class section on the edge of the city, the so-called Moscow suburb, whose mixed population already included approximately 1,700 Jews. Soon Riga’s other Jews received notices that they were to vacate their dwellings and resettle inside the ghetto.

On 12 August 1941, a ‘Resettlement Office’ with a staff of 10, started to register the new arrivals inside the ghetto. To make room for them, approximately 10,000 non-Jews were forced to leave the Moscow suburb, while 29,602 Latvian Jews were moved by force into the designated ghetto area. Within the Jewish community of Riga, some welcomed the creation of a ghetto, believing it offered some protection against the arbitrary confiscations and arrests by the Latvian police and Self-Defence units. But the process of resettlement into the ghetto was extremely difficult because of restrictions on the use of public transport, and the limited amount of housing available. The Riga city administration demanded that the Jewish community cover the expenses incurred by the non-Jews who had to move out of the designated ghetto area. Immediately after the announcement of the planned resettlement, an illicit trade emerged in accommodation for those newly arrived in the ghetto. The Latvian and Russian inhabitants who left the ghetto area, tried to make money from those Jews seeking housing in the narrowly confined ghetto area. Also, some Jewish agents earned a lot of money acting as mediators for the procurement of apartments in the ghetto, usually for large extended families. The German authorities planned for only 4 square meters per person for those living in the Riga ghetto. The ghetto also contained 24 grocery stores, two workshops, four schools, three kindergartens, and one nursing home, which were established to meet the needs of this new community. The only hospital in the Riga ghetto was the former women’s hospital ‘Linas Hazedek,’ under the direction of Professor Vladimir Minc.

The Germans ordered the creation of a Jewish Council (Judenrat) which was headed by Michael Elyashov and a Jewish Police force was established which was commanded by Michael Rosenthal. The Judenrat consisted of seven members and included the following departments: Finance, Food Distribution, Housing, Health, Labour Department, Clothing Department, Supply of Goods, and the Jewish Police. The inmates of the Riga ghetto received 175 grams of meat, 100 grams of butter and 200 grams of sugar per person each week. Under these harsh conditions, with very little food and forced labour, the ghetto inhabitants tried to live a normal life, which included the observance of Jewish religious holidays and cultural events.

Riga Main Station - Friedrich Jeckeln - centre in SS Uniform (Bundesarchiv)

The decree officially establishing the ghetto was published by the Gebietskommissar and Mayor of Riga, Hugo Wittrock, on 23 October 1941, two days before the Riga ghetto was enclosed. Work crews acted quickly and the ghetto was surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence, which was guarded by members of the 20th Latvian Police Battalion. Wittrock assumed responsibility for the Riga ghetto, including the considerable costs necessary for maintaining its infrastructure. The Germans viewed the Riga ghetto as a short term measure, they had already decided to kill most of Latvia’s Jews, during the summer and autumn of 1941, prior to the official creation of the ghetto a large number of male Latvian Jews had already been killed in mass shooting ‘ Aktions’ carried out by members of Einsatzgruppe A, with the assistance of the Latvian auxiliary police under the command of Viktors Arajs. On the orders of the Higher SS and Police Leader Ostland, Friedrich Jeckeln, almost half of the ghetto inhabitants, more than 11,000 Jews were murdered on 30 November 1941, by units of the German Order Police in Rumbula Forest, approximately 6 miles from the ghetto. The Jews residing at those addresses selected for this ‘Aktion’ received instructions to gather at the ghetto’s central square early in the morning and from there they were escorted to the killing site. During this ‘Aktion’ a rather unexpected incident happened, deportation of Jews from Germany took place and the first transport of 1,000 Jews from Berlin arrived at the Riga ghetto on the morning of 30 November 1941. Jeckeln decided to kill the arrivals from Germany along with the Latvian Jews, on his own authority, without approval from Berlin. Dr Rudolf Lange, the head of the Security Police in Latvia, refused to participate in the murder of German Jews without a specific order from the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), and he withdrew his men from the ‘Aktion.’ Thus the first part of the extermination of the Riga ghetto inmates and German Jews took place solely under Friedrich Jeckeln’s direction. The German Order Police carried out the shooting without the support of the Security Police.

The second ‘Aktion’ aimed at killing most of the remainder of the Riga ghetto Jews, took place on 8 December 1941, again using the Rumbula forest site. This time only Latvian Jews were murdered, and the Security Police actively participated in the massacre. The victims of this shooting numbered more than 14,000 people, which meant that at least 25,000 Latvian Jews had been murdered, in these two murder ‘Aktions’. Among those spared were mostly young men and women who were healthy enough to work, and these were removed to a separate part of the ghetto, on the evening of 7 December 1941, just before the second mass murder shootings had taken place. After the murder of most of Riga’s Jews, the remaining area of the ghetto gradually filled up with Jews who had arrived from the Reich, whom the Germans had incarcerated in the transit camp of Jumpravmuiza (Jungfernhof). Approximately 22,000 German, Austrian and Czech Jews arrived from the late autumn of 1941 until mid -1942. Jews from Bonn , Dortmund, Hamburg, Hannover, Leipzig, Munster, Wurzburg, Prague and Vienna and other places were deported to Riga. The German Jews renamed the streets where they lived in the ghetto after the places or cities they had been deported from. The Nazi authorities strictly forbade any contact between the Jews from the Greater German Reich and the Latvian Jews. However, there were some contact, many of the Latvian Jews spoke German fluently and assisted the new arrivals in obtaining food. The new arrivals had to adjust quickly to the strange and somewhat hostile environment of the Riga ghetto and to organise their living conditions in the dwellings vacated by the murdered Latvian Jews. The deported Jews soon established their own Jewish Council to represent their interests. In some cases, these representatives had already been elected during the three days of travel in the deportation trains. First, the Jews organised their own groups dependent on the location they were deported from, but soon a centralised internal ghetto administration was established with a social department, a labour department, a prison and a police unit. There was no Jewish administration for the distribution of housing, the German police allocated space in which each deportation group had to reside.

During the winter of 1941 and the summer of 1942, the Security Police demanded a number of young Jewish men to build the barracks of the concentration camp in Salaspils. This was a camp planned to hold Soviet Prisoners of War, which was located some 8 miles from Riga. The first group of Jewish workers who were ordered to Salaspils left on 22 December 1941. The survivors from this working group returned to the Riga ghetto as living skeletons, because the food rations were very poor, and they had to spend the nights in half-built barracks, without windows in the harsh winter. It is not known exactly how many died, as many exhausted Jews were returned to the ghetto to be replaced by new healthy workers. During the spring of 1942, the Germans initiated further ‘Aktions’ against the Riga ghetto, concentrating firstly on those Jews who were unable to work. On 15 March 1942, elderly people were selected for ‘easy work’ at a fishing company, which in fact did not exist. On 26 March 1942, a similar ‘Aktion’ took place at the Jungfernhof camp. This ‘Aktion’ resulted in the deaths of approximately 2,000 people. The Jewish ghetto police initially consisted of 42 Latvian Jewish men, who generally tried to act in the interests of the ghetto residents. They were in charge of both ghetto parts – the Latvian and the German – even after most of the Latvian Jews had been killed.

At the beginning of 1942, with the help of the police, a resistance movement in the Latvian part of the ghetto was established. People from all strata of society in this part of the ghetto were involved, including the former chief of the financial department of the Judenrat. They organised the smuggling of parts of weapons into the ghetto, where they were re-assembled. This was possible, as a number of Jews worked for the Wehrmacht sorting weapons. The resistance movement prepared a bunker where they stored food, guns and ammunition. The resistance group were betrayed under mysterious circumstances, and the German Security Police uncovered their activities. On 29 October 1942, all the members of the Jewish ghetto police were summoned to the so-called Blechplatz, and here they were shot by the German Security Police. Throughout its three years of existence, the Riga ghetto was a constantly changing entity. For example, the borders of the ghetto changed so often that its precise outline at a certain time can no longer be determined. There were reasons for this – besides the radical change of the ghetto’s initial function from one of isolation to that of a deportation camp, frequent shooting ‘Aktions’ also reduced the ghetto’s population, causing the ghetto area to be reduced on several occasions. Most of the workplaces for Jews were located outside of the ghetto, in many cases quite some distance away. To exploit their labour to the maximum, many firms kept the Jews overnight at the work sites for several weeks, to avoid the long march to and from the ghetto every day. In this way many Jews spent most of their working time outside the Riga ghetto. These practices contradicted the aim of the Germans to isolate the Jews and made it possible for Jews to contact the local population and obtain some extra food, or even to escape.

On 1 May 1942, the Generalkommissar Otto Dreschler complained that the establishment of many small labour sites for Jews, would undermine the purpose of having a ghetto, and he demanded that the firms or military institutions return the working Jews every day by 8.00 p.m. However, this order was never fully implemented. At the same time, the German authorities needed the ghetto to remain as a functioning urban area, including the maintenance of gas and electricity facilities. The Gebitskommissar was responsible for these issues, and he repeatedly sent non-Jewish mechanics into the ghetto to conduct this work. In this way, a number of non-Jews received permission to enter the ghetto and they gained an impression of living conditions there.

The liquidation of the Riga ghetto occurred incrementally. On 8 July 1943, Heinrich Himmler issued a secret order to the Riga Gebeitskommissar that all Jews had to be confined within concentration camps containing ‘not less than 1,000 people.’ This order removed responsibility for the 11,701 Jews in Riga from the Gebeitskommissar. Now the German Security Police was solely responsible for the concentration and exploitation of Jews in Latvia.In the autumn of 1943, the Jews of Riga ghetto were gradually transferred to the authority of the Kaiserwald concentration camp, which had 23 sub-camps, mostly composed of work-sites, where the Jewish workers were still needed. On 2 November 1943, 1,000 Jews from the Riga ghetto were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp, and this transport arrived in Birkenau on 5 November 1943, and 150 were selected for labour, whist 850 were killed in the gas chambers. The last ghetto inmates approximately 5,000 Jews were transferred to the Kaiserwald camp, and thus the Riga ghetto was no more.

Sources:

The Yad Vashem Encyclopaedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust Volume II, Yad Vashem, 2009.

D. Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle, Henry Holt and Company, New York1989

Photograph – Chris Webb Archive & Bundesarchiv

© Holocaust Historical Society 2017