Kristallnacht

Kristallnacht - Aftermath in Magdeburg - November 1938 (Bundesarchiv)

On October 27, 1938, less than three weeks after annexing the Sudetenland, Hitler struck again, this time against the Jews, expelling from Germany some eighteen thousand Jews, who although having lived in Germany since 1918, had been born in the former Polish provinces of the Russian Empire. The expulsion, eastward to the Polish border, was a swift and brutal act, much in keeping with Nazi methods.

One of the eighteen thousand Jews expelled from Germany, Zindel Grynszpan, had been born in the town of Radomsko, in Russian Poland, during 1886. Since 1911, he had lived in Hannover. His eldest son, Hirsch Grynszpan, had gone to Paris, as a student, in 1936. The rest of the family, Zindel, his wife, his daughter and second son, remained in Hannover.

Zindel Grynszpan recalled:

'On the 27th October 1938, it was Thursday night at eight o'clock - a policeman came and told us to come to Region II. He said, 'You are going to come back immediately; you shouldn't take anything with you. Take with you your passports.'

When I reached the Region, I saw a large number of people; some people were sitting, some standing. People were crying, they were shouting, 'Sign, sign, sign.' I had to sign , as all of them did. One of us did not, and his name, I believe, was Gershon Silber, and he had to stand in the corner for twenty-four hours.

They took us to the concert hall on the banks of the Leine and there, there were people from all the areas, about six hundred people, There we stayed until Friday night; about twenty-four hours; then they took us in police trucks, in prisoners lorries, about twenty men in each truck, and they took us to the railway station. The streets were black with people shouting, 'The Jews out to Palestine.'

After that, when we got to the train, they took us by train to Neu Bentschen, on the German -Polish border. It was Shabbat morning; Saturday morning. When we reached Neu Bentschen at 6 a.m. there came trains from all sorts of places, Leipzig, Cologne, Dusseldorf, Essen, Bielefeld, Bremen. Together we were about twelve thousand people.

Neu Bentschen Railway Station (Chris Webb Archive)

When we reached the border, we were searched to see if anybody had any money, and anybody who had more than ten marks, the balance was taken from him. This was the German law. No more than ten marks could be taken out of Germany. The Germans said, 'You didn't bring any more into Germany, and you can't take any more out.'

The SS were giving us, as it were, protective custody, and we walked two kilometres on foot to the Polish border. They told us to go - the SS men were whipping us, those who lingered they hit, and blood was flowing on the road. They tore away their little baggage from them, they treated us in a most barbaric fashion - this was the first time that I'd ever seen the wild barbarism of the Germans.

They shouted at us: 'Run, Run!' I myself received a blow and I fell into a ditch. My son helped me, and he said, 'Run, run, dad - otherwise you'll die!' When we got to the open border- we reached what was called the green border, the Polish border - first of all, the women went in.

Then a Polish general and some officers arrived, and they examined the papers and saw that we were Polish citizens, that we had special passports. It was decided to let us enter Poland. They took us to a village of about six thousand people, and we were twelve thousand. The rain was driving hard , people were fainting - some suffered heart attacks; on all sides one saw old men and women. Our suffering was great - there was no food - since Thursday, we had not wanted to eat any German bread.'

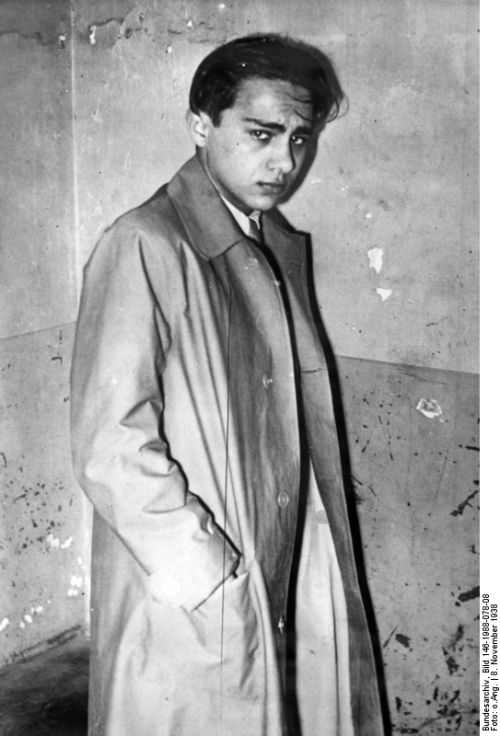

Hirsch Grynszpan (Bundesarchiv)

The conditions at the Polish frontier town of Zbaszyn were awful, and Zindel Grynszpan later recalled, that the Jews were put in stables, still dirty with horse dung. At last a lorry with bread arrived from Poznan, but at first there was not enough bread to go round. Zindel Grynszpan decided to send a postcard to his son Hirsch, in Paris, describing the family's experiences. The young man, enraged by what he read, went to the German Embassy in Paris, and on November 6, 1938, shot the first German official who received him, Ernst vom Rath.

On November 9, 1938, Ernst vom Rath died, and when Hitler was informed of this whilst in Munich, an unprecedented wave of violence broke over Germany's remaining three hundred thousand Jews.

Among those who witnessed the orgy of violence in the streets was Wim van Leer, a twenty-five year old Jew from Holland. Walking in a Leipzig street, he saw a truck draw up a few houses down the road from him, and some twenty louts jumped down. Van Leer watched as Stormtroops rang the door bells, smashed the glass windows in the doors if there was no reply, and entered the Jewish houses. 'Suddenly,' he later recalled, 'third-floor balcony doors were flung open, and Stormtroops appeared, shouting to their mates below. One yelled something about all blessings coming from above, and, in expectation, that part of the pavement beneath the balcony was cleared. Next they wheeled an upright piano on to the balcony and, smashing the balustrade with one mighty heave - there must have been eight of them - they pushed the piano over the edge. It nose-dived on to the street below with a sickening crash as the wooden casing broke away, leaving what looked like a harp standing in the middle of the debris.'

Throughout Germany bonfires were lit in every neighbourhood where Jews lived. On them were thrown prayer books , Torah scrolls and countless volumes of philosophy, history, and poetry. In thousands of streets, Jews were chased, reviled and beaten up. In twenty -four hours of street violence, ninety-one Jews were killed. More than thirty thousand were arrested and sent to concentration camps. Before most of them were released two to three months later, as many as a thousand had been murdered, 244 of them in Buchenwald. A further eight thousand Jews were evicted from Berlin: children from orphanages, patients from hospitals, elderly people from old people's homes. There were suicides, ten at least in Nuremberg, but it was forbidden to publish death notices in the press.

It was not by the killings. nor the arrests or the suicides, that the night of November 9, 1938, will be remembered. During the night, as well as breaking into tens of thousands of shops and homes, the Stormtroops set fire to hundred and ninety-one synagogues; or if it was thought that fires may endanger nearby buildings, smashed the synagogues as thoroughly as possible with hammers and axes. The destruction of the synagogues led the Nazis to call that night the Kristallnacht, or 'night of broken glass.'

Among the witnesses to these events was Dr. Arthur Flehinger from Baden -Baden. Later he recalled how all Jewish men in Baden-Baden were ordered to assemble on the morning of November 10. Towards noon they were marched through the streets to the synagogue. Many non-Jews resented the round-up. 'I saw people crying while watching from behind their curtains,' Dr Flehinger later wrote, and he added: 'One of the many decent citizens is reported to have said, 'What I saw was not one Christ, but a whole column of Christ figures, who were marching along with heads high and unbowed by any feelings of guilt.'

While being marched up the steps of the synagogue, several Jews fell, only to be beaten until they could pick themselves up. Once inside the synagogue, the Jews were confronted by exuberant Nazi officers and SS men. Dr. Flehinger himself was ordered to read out passages from Mein Kampf to his fellow Jews. 'I read the passage quietly, indeed so quietly that the SS man posted behind me repeatedly hit me in the neck,' Dr Flehinger later recalled. 'Those who had to read other passages after me were treated in the same manner. After these 'readings' there was a pause. Those Jews who wanted to relieve themselves were forced to do so against the synagogue walls, not in the toilets, and they were physically abused while doing so.'

The Jews were led away. Within an hour, the synagogue was in flames. 'If it had been my decision,' one of the SS men remarked, 'you would have perished in that fire.' Dr. Arthur Flehinger managed to leave Germany in 1939, and he settled in England.

In Hoengen, a small village near Aachen, the tiny Jewish community had built its synagogue in 1926: now twelve years later, Michael Lucas, a butcher by trade, whose house was opposite the meadow, watched from his window as Stormtroops stood on guard. His nephew Eric later recalled:

'After a while, the Stormtroops were joined by people who were not in uniform; and suddenly, with one loud cry of, 'Down with the Jews,' the gathering outside produced axes and heavy sledgehammers. They advanced towards the little synagogue which stood in Michael's own meadow, opposite his house. They burst the door open, and the whole crowd, by now shouting and laughing, stormed into the little House of God.

Michael, standing behind the tightly drawn curtains, saw how the crowd tore the Holy Ark wide open; and three men who had smashed the ark, threw the Scrolls of the Law of Moses out. He threw them - these Scrolls, which had stood in their quiet dignity, draped in blue or wine-red velvet, with their little crowns of silver covering the tops of the shafts by which the Scroll was held during the service - to the screaming and shouting mass of people which had filled the little synagogue.

The people caught the Scrolls as if they were amusing themselves with a ball-game - tossing them up into the air again, while other people flung them further back until they reached the street outside. Women tore away the red and blue velvet and everybody tried to snatch some of the silver adorning the Scrolls. Naked and open, the Scrolls lay in the muddy autumn lane; children stepped on them and others tore pieces from the fine parchment on which the Law was written - the same Law which the people who tore it apart had, in vain tried to absorb for over a thousand years.

When the first Scroll was thrown out of the synagogue, Michael made a dash for the door. His heart beat violently and his senses became blurred and hazy. Unknown fury built up within him, and his clenched fists pressed against his temples. Michael forgot that to take one step outside the house amongst the crowds would mean his death. The Stormtroopers who still stood outside the house watching with stern faces over the tumultuous crowd which obeyed their commands, without really knowing it, would have shot the man, quietly, in an almost matter of fact way. Michael's wife, sensing the deadly danger, ran after her husband, and clung to him, imploring him and begging him not to go outside. Michael tried to fling her aside, but only her tenacious resistance brought him back to his senses. He stood there, in the small hall behind the front door, looking around for a second, as if he did not know where he was. Suddenly, he leaned against the wall, tears streaming from his eyes, like those of a little child.

After a while, he heard the sound of many heavy hammers outside. With trembling legs he got up from his chair and looked outside once more. Men had climbed on to the roof of the synagogue, and were hurling the tiles down, others were cutting the cross beams, as soon as they were bare of cover. It did not take long before the first heavy grey stones came tumbling down, and the children of the village amused themselves as they flung stones into the many coloured windows.

When the first rays of a cold and pale November sun penetrated the heavy dark clouds, the little synagogue was but a heap of stone, broken glass and smashed up woodwork. Where the two well cared for flowerbeds had flanked both sides of the gravel path leading to the door of the synagogue, the children had lit a bonfire and the parchment of the Scrolls gave enough food for the flames to eat-up the smashed -up benches and doors, and the wood, which only the day before had been the Holy Ark for the Scrolls of the ;Law of Moses.'

Similar scenes were repeated throughout the Reich. In Worms, Herta Mansbacher, the assistant principal of a Jewish School, was among those who managed to put out the fire in the synagogue, but a gang of louts soon arrived to light it again. In a gesture of defiance, Herta Mansbacher barred the entrance. 'As much as they sought to put a Jewish house of worship to the torch,' the historian of Worms Jewry has written, 'she was equally willing to stop them, even at the risk of her own life.' Herta Mansbacher was eventually pushed aside, and the synagogue burned to the ground. Herta Mansbacher lived through these events, but was deported on March 25, 1942, to the Piaski transit ghetto in Poland. She was murdered in the Belzec death camp, during 1942.

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, German Jewry was 'fined' for the damage done. The fine, a thousand million marks, was levied by the compulsory confiscation of twenty per cent of the property of every German Jew. This confiscation was promulgated by government decree on November 12, 1938. Three days later, following more than five years of being pilloried and discriminated against in the classroom, German Jewish children were finally barred from German schools.

Sources

M. Gilbert, The Holocaust, William Collins, London 1986

Bundesarchiv Gedenkbuch -online resource

Photographs -© Holocaust Historical Society 2019