Wlodawa

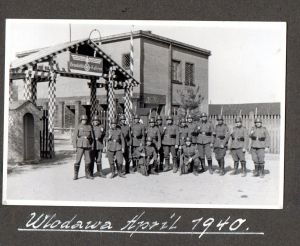

Wlodawa German Barracks 1940

Wlodawa is situated on the current Polish border with Belarus, about 62 miles north east of Lublin. On the eve of the Second World War there were 5,650 Jews living in the town. After heavy bombing at the start of the campaign, German forces occupied Wlodawa on 18 September 1939. Shortly after German Security forces rounded up hundreds of Jewish men and herded them into the Great Synagogue, threatening to burn it down. However, the men were released the next day in exchange for a selected bunch of hostages, who were also released after a beating, as the German forces suddenly retreated. The Soviets then occupied Wlodawa for a few days before withdrawing again behind the River Bug in accordance with the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. A number of Jews took the opportunity to flee Wlodawa and go with the Russians.

The Germans re-occupied Wlodawa in October 1939, setting up a civil administration several weeks later. With the establishment of the Generalgouvernement, the town lay within the Chelm County (Kreis Cholm), within the Lublin District. The Kreishauptmanner were Werner Kalmus (October 1939 to February 1940), Gerhard Hager (May 1940 to July 1941), Hans Augustin (September 1941 to March 1942), Dr Werner Ansel (April 1942 to November 1942), Claus Harms (December 1942 to May 1944), and once more Werner Ansel (July 1944). By 1941 a Landkommissariat of the Kreishauptmannschaft had been established in Wlodawa. Furthermore there was a Grenzpoliposten (Border Police Post), which was subordinated to the KdS of the Security Police in Lublin. From late 1939, the Wlodawa Border Police post was headed by SS- Untersturmfuhrer Richard Nitschke, his deputy from 15 January 1942, was SS-Oberscharfuhrer Schonborn. They were responsible for the town and its surroundings up to the village of Sobibor, which was located some 7 miles to the south of Wlodawa.

A Jewish Council (Judenrat) was established by the German authorities in October 1939. Members of the council were Szyja Somer, who was president, Abram Kahan, vice-president, Szyja Lichtenberg, Rabbi Mendel Morgenstern, Mejr Borensztejn, Jankiel Richtman, Ignacy Bransztater, Dr Springer, Hersz Buchbinder, Hersz Bober, and Antoni Gruber. The Judenrat and its small Jewish police force were responsible not only for collecting money but also for providing German officials with jewellery, leather boots, furs, and other luxury items which of course were only available on the black market.

The Germans immediately instituted a series of economic measures against the Jews. In the spring of 1940, all Jewish stores were expropriated or placed under trusteeship. Thus the Nazis rapidly proceeded with the elimination of the Jews from economic life. The Jews were also subjected to extortion: in October 1939, the community had to raise a ‘contribution’ of 50,000 zlotys within 24 hours. Early in 1942 the Kreishauptmann demanded 3 kilograms of gold from the Wlodawa Judenrat to avert a planned ‘resettlement Aktion.’ The Jews collected the required gold, apparently delaying the ‘Aktion’ by several months.

During the early stages of the occupation, possibly in late 1939, the Jews were removed from some of the main streets in the town and were given only ten minutes to leave. Sara Umelinsky, a Jewish survivor, recalled that her family had to move in with another family in a district that became the ‘Jewish Quarter,’ but she did not call it a ghetto. Other survivors also mention the existence of a Jewish quarter, but did not give any details. Several waves of Jewish deportees were sent to Wlodawa, which is described in one account as a Judenstadt or collection point for Jews. For example in December 1939, several hundred Jews were deported from Kalisz, in the Warthegau, in Wlodawa, where the local community had to provide them with assistance. In mid-March 1942, 785 Jews arrived by train from Mielec, where the local Jewish population were completely resettled. A further transport of Jews arrived from Vienna. This transport of 1,000 men, women and children left Aspang station in Vienna, on 27 April 1942, and only 3 survived the Holocaust.

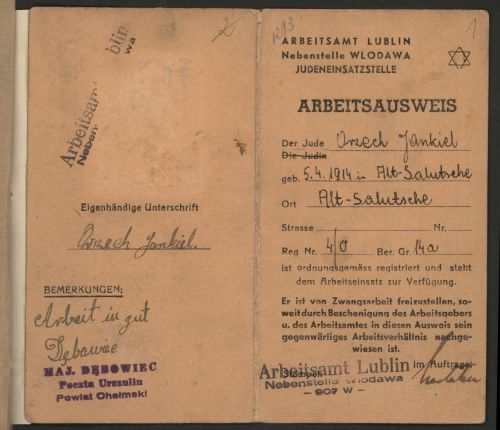

The Nazi administration had a strong interest in the work-force of the local population and thus established an Arbeitsamt (labour office) soon after the occupation of the town, under the supervision of Gutsche and Gröh. This office handed the responsibility for supplying workers onto the Judenrat, where Brettmehl managed this task. The Jewish Council also had to pay the pitiful salaries and distribute food rations among the Jewish workers. Morever, with the money received from ‘hiring’ out ghetto inhabitants to interested companies, the council was able to organise food for the ghetto inhabitants. Cleaning and housekeeping jobs for the Germans existed, as well as opportunities at former Jewish handicraft businesses and stores.

The largest employer was the German company Rohde, which conducted drainage projects for the Wasserwirtschaftsamt (Water Administration Office) Chelm, the local executive was Bernhard Falkenberg. Initially, he employed 180 Jews, but by 1942, their number had increased to some 1,500. They still lived in the town and walked to the work sites south west of Wlodawa in the morning. At the site, Falkenberg was known for his generosity in providing food for the Jews and especially for protecting them against abuses. The labour camp had many more Jews than were really needed for the workload there. Thus, Bernhard Falkenberg was honoured as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1969 for his humane treatment of the Jews working for him.

Between 18 May and 23 May 1942, Kreishauptmann Werner Ansel ordered the first major anti-Jewish ‘Aktion’ in Wlodawa. About 1,200 Jews who were unable to work were forced by the German police and Ukrainian auxiliaries to assemble by the Kino Zacheta (cinema) at gunpoint. Then they were escorted to the railroad station and deported to the nearby Sobibor death camp, which had been erected with the assistance of 150 Jews from Wlodawa. During the deportation ‘Aktion,’ the Germans and their collaborators staged a massacre in the town, which claimed an even larger number of Jewish victims. Roughly one week later, some of the survivors wrote a coded letter to the ‘Oneg Shabbat’ archive in Warsaw filled with biblical allusions regarding the recent deportation.

A further deportation ‘Aktion’ in the summer of 1942 targeted children aged between 10 and 14. With untold brutality the Germans separated several hundred children from their parents and transported them to Sobibor. To calm them down Rabbi Mendel Morgenstern accompanied them and went to his death with the children. On 24 October 1942, the Germans conducted another large-scale ‘Aktion’ against the Jews of Wlodawa. About a week before the ‘Aktion,’ Richard Nitschke ordered that the Jews from the surrounding villages, including Hansk and Suchawa and some from nearby work camps be brought to Wlodawa. The town became so full that many Jews were sleeping outside in the rain. Then early in the morning of 24 October 1942, members of the SD, the Gendarmarie, Schutzpolizei and Ukrainians from the SS training camp at Trawniki started arresting the Jews. They were collected in the sports stadium and then taken to the station. Only about 500 workers were exempt from the deportation and allowed to remain, most of them working for Falkenberg. In all some 5,000 of Jews from Wlodawa, along with more than 2,000 Jews from Chelm, who had been marched to Wlodawa, were murdered in the gas chambers of the Sobibor death camp.

At the end of October 1942, the German authorities announced that Wlodawa would be one of the few remaining towns in Distrikt Lublin where Jews would be permitted to reside in a ‘Jewish residential area’ (Judenwohnbezirk). However, the real purpose of this announcement was mainly to lure Jews back out of hiding. A remnant ghetto was created in Wlodawa which consisted of only two streets, Wyrykowska and Jatkowska. It was directly next to a new camp that had been established to hold the more than 500 remaining Jews with work permits, i.e. craftsmen. Both camps were surrounded by high barbed-wire fences. The ghetto gradually filled up with hundreds of Jews who emerged from hiding. There were ‘Aktions’ at the end of October or early November 1942, where the Germans rounded up several hundred more Jews and deported them to the Sobibor death camp, though some were murdered at the train station.

Wlodawa Synagogue 2004

After this ‘Aktion’ the Jews in the labour camp received larger monthly food rations consisting of 7.5 kilograms of bread, 400 grams of semolina, 400 grams of sugar, 400 grams of Polish poppy-bread, 200 grams of jam, and 500 grams of horsemeat. They were subjected to heavy forced labour for the Water Administration Office. They had to travel to work marching between 6 and 10 miles a day. A small number of Jews were permitted to practice their old professions, but their rations were much smaller. The ghetto on Jatkowska Street continued to exist as a holding place for Jews brought in from the countryside, but conditions there were much worse. On 30 April 1943, the camp and ghetto were both liquidated and some 2,000 Jews were deported to Sobibor death camp, where they were murdered.

Arbeitsausweis for Yankiel Orzech (Nebenstelle Wlodawa)

Of 50 Jewish girls who were retained to sort out Jewish belongings and property from the ghetto after the ‘Aktion,’ some escaped to a nearby manor, while the rest were killed on the spot, shortly afterwards. Jewish Wlodawa had ceased to exist, although a few Jews managed to escape the round-ups and fled to the forest to join partisan groups, for instance the group led by Mosze Lichtenberg. When the Red Army liberated the town in July 1944, there were no Jews living there.

Sources:

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, Collins London 1986

Photographs – Chris Webb Archive

Document - Archiwum Panstwowe w Lublinie

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018