Warsaw

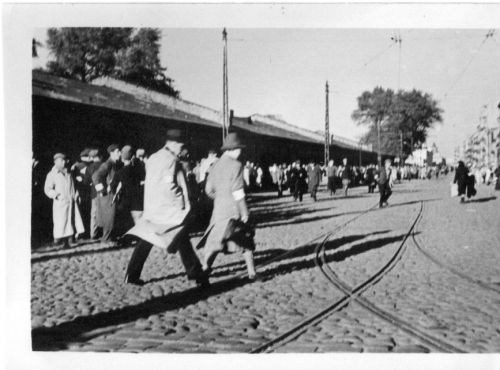

Warsaw Ghetto - Jewish Tram

Warsaw became the capital of Poland in 1596, the city flanks both sides of the Vistula River, two thirds of the cities area lying on the west bank and one third on the east bank. Jewish people lived in Warsaw from the 15th century, and during the 19th century the Jewish population of Warsaw grew rapidly, becoming the largest Jewish community in Europe, and by the 20th century the world’s second largest behind New York. Jews were to be found in every part of the city, but predominantly in the Northern part, with many apartment houses and certain streets inhabited exclusively by Jews. In 1935 the city limits covered an area of 54 square miles with a population of 1.3 million people. On the eve of World War Two the Jewish population in Warsaw numbered 337,000 about 29% of the total population of the city, this figure rose to 445,000 by March 1941.

Following the German invasion of Poland on 31 August 1939, the German ‘Blitzkrieg’ swept through Poland, and reached the southern and western parts of the city on 8 and 9 September 1939. Within a few days(until 28 September) the Germans had surrounded the city from all sides, and launched deadly air attacks, and artillery shelling, which caused heavy damage to buildings and significant loss of life. Adam Czerniakow who was to become the Chairman of the Warsaw Jewish Council (Judenrat) wrote in his diary on 14 September 1939 At the Jewish cemetery, 130 bodies burned by incendiary bombs on 13 September and on 15 September: “Heavy artillery fire mainly in the area where I live. Blazing fires lit up the city”

On 23 September 1939 MayorStefan Starzynski appointed Czerniakow as Chairman of the Jewish Community in Warsaw. Czerniakow wrote in his diary: A historic role in a besieged city: I will try to live up to it.

From the first days of the occupation the Jews were subjected to attacks and discrimination, such as being driven from food lines, seized for forced labour and violated for their traditional clothing and hairstyles. Teachers, craftsmen, professionals and members of welfare and cultural institutions lost their positions, without any compensation, or little prospect of obtaining similar positions.

On 23 November 1939 Hans Frank the Governor- General issued a decree that all Jewish men, women and children over 10 years of age were required to wear in public a white armband with a blue Star of David. In addition Jewish shops were to be marked, restrictions proclaimed on travel by train, and radios were confiscated from Jews and Poles from 1 December 1939. The harshest measures came with a number of decrees on economic affairs, such as the prohibition of non-Jews buying or leasing Jewish enterprises without obtaining a special permit for this purpose, decreed by Dr Ludwig Fischer, the District Governor of Warsaw on 17 October 1939.

In place of the many pre-war institutions, only two frameworks were allowed to function under the Germans, these were the Jewish Council (Judenrat) and the Jewish Self-Help welfare organisation. The Jewish Council was a new body, set up as per Reinhard Heydrich’s edict as a first part of the Final Solution of the Jewish problem outlined at a secret conference of high police officials on 21 September 1939. that each community is to select a Jewish Council of not less than 24 members.

In November 1939 more decrees followed concerning the handling of money by Jews, they were ordered to deposit their money in blocked bank accounts. The bank could release no more than 250 zloty’s per week to the holder of the account. These orders made it impossible for Jews to carry on economic activity in the open, and particularly outside of Jewish circles. In addition to blocking Jewish accounts and putting a stop to economic activity, the Germans also embarked upon the confiscation of Jewish firms, excluding small stores in the Jewish areas. Jewish managers and staff were often removed from their positions, only being retained if this suited the new owners. Even in the early stages of the occupation the assets accumulated in the past, were sold to ensure that food could be obtained, and that life could continue. As time went on and resources were exhausted the Jews faced a slow torturous death, from starvation and disease.

The Jewish Council headquarters was on Grzybowska Street (later at 19 Zamenhofa from August 1942) and amongst the leading men who worked there and their roles were;

• Housing Office – Bart

• Health Division – Milejkowski

• Labour Commission – Jaszunski

• Provisioning Department – Abraham Gepner, Sztolcman, Winter, Graf

• Order Service – Josef Szerynski

• Production – Orlean and Glicksman

• Workers Representative – Zygielbojm

The Jewish Council was the sole official body that the German authorities dealt with, thus facilitating the stranglehold the occupying forces had over the Jewish people. The Jewish Council staff at its height numbered 6,000. Before long it became evident that the number of welfare cases was growing and that an organisation had to be created and equipped that would meet their needs of the ghetto population. The American Joint Distribution Committee sponsored ZTOS (Zydowskie Towarzystwo Opieki Spolecznej - Jewish Mutual Aid Society) to lend assistance to 250,000 Jewish people during the Passover of 1940. This was achieved by setting up soup kitchens, which provided a bowl of soup and a piece of bread to all comers. When this operation was at its height, more than one hundred such soup kitchens were in operation throughout the Jewish quarter. In March 1940 a wave of violent attacks on Jews was launched by Polish gangs and individual Jews were robbed in the street, whilst others looked on passively. During the Easter season these attacks turned into a pogrom, which continued for eight days, and only ended when the German authorities ordered it to cease.

The first attempt to set up a Jewish living area had been proposed by the SS in November 1939, but at the time the Military Governor General Karl Ulrich von Neumann- Neurode put a stop to the plan. In February 1940, however, Waldemar Schön, the official in charge of the evacuation plans (Abteilung Umsiedlung), was ordered to draw up plans for the establishment of the ghetto. Various proposals were considered, one was relocation to the eastern part of the city, over the Vistula River, in the suburb of Praga. On 12 October 1940, which was the Jewish Day of Atonement, Czerniakow was informed of the decree establishing a ghetto, and was given a map of both the ghetto and the German quarter.

On 14 October Dr Fischer’s proclamation of the ghetto was published, the creation of the ghetto meant that 140, 000 Polish people had to vacate their homes, and 104,000 Jews had to take their place. Hence approximately 30% of the population of Warsaw was packed into only 2.4% of the city’s area. In mid-November 1940 the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw was sealed off by a high wall, its construction took many months to complete. The ghetto wall was 3.5 meters high topped with glass and barbed wire. The construction firm responsible for building the wall was the German firm Schmidt & Munstermann, who were paid by the Jewish Community to build the wall. This same firm helped to build the Treblinka death camp two years later.

The Germans did not use the term ghetto, but called the area the Jewish Quarter (Jüdisches Wohnbezirk). A Jewish Police force (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst) was established primarily to combat smuggling, and generally to keep order with the ghetto, at its height numbered 2000 members. The leader of the Jewish Police appointed by Czerniakow was Josef Szerynski, a Polish police colonel, whose name had been Sheinkman, before his conversion to Catholicism. Szerynski was arrested in May 1942, and Jakob Lejkin his deputy took command. Szerynski survived an assassination attempt by the Jewish Underground in August 1942, but took his own life in January 1943.

The daily food rations allocated to the Jews of Warsaw consisted of only 181 calories, about a quarter of the rations Poles were granted, and much less than what was allocated to Germans. This totally inadequate level of food, reduced the ghetto to a slow murder through mass starvation, unsurprisingly the mortality rates reflected this:During 1941 deaths rose from 898 a month in January, to a peak in August of 5560, and right through to May 1942 where 3,636 died. The average monthly mortality rates for the seventeen months January 1941 – May 1942 was 3882.

The Ghetto ties with the outside world were handled via an agency called the Transferstelle, this agency was in charge of the traffic of goods entering and leaving the ghetto. The first official in charge of this office was Alexander Palfinger, who was succeeded by Helmut Bischoff. In May 1941 a lawyer from Berlin Heinz Auerswald was appointed Kommissar of the Jewish quarter on behalf of the German authorities. Other officials that Czerniakow had to deal with frequently were Ludwig Leist (City Plenipotentiary), Untersturmführer Karl Georg Brandt and SS-Oberscharführer Gerhard Mende of the Security Police. Auerswald was in almost daily contact with Czerniakow, whilst every Saturday Czerniakow and Szerynski reported to Brandt and Mende at Szucha Avenue on ghetto matters.

During 1940 approximately 11,000 Jews were sent to labour camps in Warsaw, Lublin and Krakow, some were taken to Belzec labour camps, building fortifications on the soviet border. Jurek Furstenberg who was assassinated in 1943 by the Jewish underground, visited the labour camp and reported back on the terrible conditions there.

An agency known as the ‘13’ which took its name from its headquarters at 13 Leszno Street,was headed by Abraham Gancwajch originally from Lodz. The agency was sponsored by the SD/ Security Police, and was founded in December 1940 to combat usury and profiteering. Gancwajch was an orator and tried to usurp Czerniakow as head of the Jewish Council, but failed in these ambitions, and was killed by the Germans in Pawiak prison, when he had outlived his usefulness. Two other refugees from Lodz Moryc Kohn and Zelig Heller, who at first were associates of Gancwajch, but broke away from him, set up various commercial enterprises, such as the horse drawn wooden trams that transported passengers within the ghetto. Kohn and Heller met the same fate as Gancwajch. Josef Ehrlich nicknamed Kapota, because of the caftan he wore, who also worked for the SD/ Police, was assassinated by the Germans in 1943.

German manufacturers appeared in the ghetto in the summer of 1941, having been granted authorisation to operate in the Warsaw district. First to appear on the scene in July 1941 was Bernard Hallmann, owner of a carpentry firm. In September 1941 the Fritz Schulz Company a Gdansk (Danzig) fur establishment became active in the ghetto. the giant among those German businessmen, a manufacturer of textile goods, who employed 4,500 Jewish workers initially. Többens played a leading role during the deportations in the summer of 1942, as people flocked into the perceived safe haven of the workshops, often paying large sums of money for the privilege, at one point Többens employed about twelve thousand workers.

A vital part of the Jewish daily life was the smuggling operations, through buildings that bordered the ghetto, or through the ghetto gates, and over the walls. Jews, Poles and Germans were all involved with bribery playing a large factor. Children and women were also engaged on a smaller scale, risking their lives, and often paying the ultimate sacrifice-that is shot on the spot by the Germans, or captured by the Jewish Police, and probably executed later. According to Czerniakow food smuggled into the ghetto represented 80% of all the products brought in.

Men such as Yitzhak Gitterman and Emanuel Ringelblum organised and led a variety of self-help agencies, among those ZTOS and Centos(Centralne Towarzystwo Opieki nad Sierotami), the Central Association for the Care of Orphans, which ran schools and provided food, clothing and shelter. These self-help organisations employed hundreds of people, offering a daily bowl of soup as salary. They operated independently from the Jewish Council.In January 1942 as the financial support from the American-Jewish Joint Distribution Committee were ceased due to the entrance of USA into the Second World War during December 1941. The self-help organisations ceased relying upon voluntary donations and instead were empowered to impose taxes.

Amongst the most important elements of self-help were the “house committees”, which functioned in almost every apartment house. They imposed a double monthly payment on the residents, one for the benefit of self-help, the other for the needs of the apartment house itself. They collected food from every family that was able to make a contribution, and distributed the food to starving families. A person carrying a bucket went from apartment to apartment, collecting food, goods and clothing from the more fortunate, who donated whatever they could spare. The house committees also assessed everybody’s resources and imposed a monthly payment upon each household. Money and goods were given to the central fund, which supported the soup kitchens. To enforce its effectiveness, the house committees used the only weapon available to them, shaming those who were selfish. Families who were able to make a contribution but refused to do so, found their names displayed at the entrance to their apartment building.

The Germans tried to ban private and public prayer services, but the Jews continued with daily services in private homes. In the spring of 1941, the ban was abolished and the synagogues were permitted to re-open. The Great Synagogue on Tlomacki Street was re-opened in June 1941, in a festive ceremony. Rabbi Kalonymos Kalmisch Shapira, the Hasidic rabbi of Piaseczno maintained his congregation in the ghetto and preached to them on the Sabbath. Schools were prohibited in the ghetto, but Czerniakow who cared passionately about the young and education, asked the German authorities to allow schools to be re-opened. In 1941 permission was granted to open the schools for several elementary school classes. These school classes started in October 1941, and indeed were the only classes in the history of the ghetto. In the ghetto during the autumn of 1941 finally 16 schools were opened under auspices of the pre-war Jewish educational organisations. About 10,000 Jewish children were enrolled in these ghetto schools (about 20% of the Jewish children in the ghetto).

While normal schools were banned in the ghetto, the Jewish Council was permitted to maintain the vocational training schools, sponsored by the “ORT” organisation. ORT was derived from the Russian “Obshchestvo Remeslennogo i zemledelcheskogo Truda”, loosely Trades Manufacturing Development Organisation, was designed to increase production among Jewish artisans. The first training courses were opened in 1940, but they reached their maximum development after the ghetto was established. In mid-1941 the total number of students attending these courses was 2,454.

Cultural life in the ghetto flourished despite all the privations, these were conducted by the underground organisations, “The Yiddishe Kultur Organizatsye (Yikor) and Tekumah. Yikor was founded by Menachem Linder, and Tekumah was headed by the historian Menachem Stein, Lipa Bloch, Menachem Kirschenbaum, and Yitzhak Katzenelson. Sponsored literary evenings and concerts were held to keep alive the spirit of Jewish culture, and history- remarkable given the Germans desires to destroy any vestiges of their heritage.Well known writers and poets continued to work in the ghetto - Itzhak Katzenelson, Israel Sztern, Jehoszua Perle, Hillel Zeitlin, Peretz Opoczynski and Kalman Lis. Theatrical groups gave performances, well known actors such as Michael Znicz, Zigmunt Turkow and Diana Blumenfeld appeared on stage. There were two Polish and one Yiddish theatre’s were established. The audience mostly consisted of the ghetto elite, who preferred light entertainment to forget the horrors of daily life.

A unique and important enterprise created in the ghetto was the Ringelblum archive, code named “Oneg Shabbat” (Joy of Sabbath). Whilst it was not directly initiated by political bodies, the archive depended on the support of public leaders and the underground organisations. The extant material, collected by the Ringelblum archive consisted of tens of thousands of pages, documents, notes, diaries and a rich collection of underground newspapers. It is the most important collection for research on the fate of Jews under the Nazi occupation of Warsaw and Poland in general.

In the months leading up to the Great Deportation action which commenced on 22 July 1942, the ghetto was gripped with rumours and foreboding regarding deportations. It was common practice prior to large-scale deportations, for the German Security police forces to carry out a raid on the ghetto, and on 18 April 1942, this particular raid was probably conducted by Brandt himself. There were sixty people on the wanted list, fifty-two were killed, some of the victims were involved in the underground movements, some were known to have grown wealthy, whilst some belonged to Gancwajch’s inner circle. The dead included Blajman and Menachem Linder. Others wanted by the Gestapo such as Yitzhak Zuckerman and Lonka Kozibrodzka of Dror- HeHalutz Underground movement, were warned and were not at home when the Germans called. The night became known as the “Night of Blood” or the “Bartholomew’s Night” of the Warsaw ghetto.

About a week before the fateful deportations, Hermann Höfle arrived in Warsaw, with a company of officers and soldiers. Höfle, who was Globocnik’s chief of staff for Aktion Reinhardt and other members of the Security forces directed the progress of the operation from two centres within the ghetto. They worked closely with Warsaw based SS and Police staff. The SS Police Leader for Warsaw was Ferdinand von Sammern- Frankenegg. The commanders of Aktion Reinhardt, which comprised of about a dozen officers, sergeants and soldiers, set up its headquarters at 103 Leszno Street, after evicting the Jews from the building. The second command post was established in the headquarters of the Jewish Police on Ogrodowa Street and was manned mainly by SS and Gestapo men who had been stationed in Warsaw for some time, such as Brandt, Mende, Gottlieb Höhmann, Walter Witossek, Max Jesuiter and Gerhard Stabenow.

Ber Warman, a Jewish policeman, who guarded 103 Zelazna Street, wrote at the end of August/ early September 1942 that SS men started to live there. Before the end of August 1942 the Befehlsstelle (order HQ) was on 17 Ogrodowa Street, at the Jewish police headquarters. At the door to one of the rooms was a plaque that read Gastzimmer des SS-Sonderkommando Treblinka (Guest room of the SS special Command Treblinka)

At 10 a.m. on 22 July 1942 Hermann Höfle, Georg Michalsen and Hermann Worthoff from Lublin and other officers visited Czerniakow at the Jewish Council offices. Höfle dictated to the Jewish Council the resettlement order, which appeared on official wall posters by midday. The main orders were:

All Jews will be resettled to the East regardless of age and sex.

With the exception of:

Jews working for German institutions or companies

Jews working for the Judenrat

Jewish Hospital staff

Members of the Jewish Order Service

Wives and children of the above mentioned persons

Patients in Jewish Hospitals on the first day of the resettlement action

Every resettled Jew will be allowed to bring 15kg of luggage and all valuables, gold jewellery, money etc.

Provisions for three days must be taken.

The resettlement will start on 22 July 1942 at 11 o’clock

The Judenrat is responsible for the delivery of 6,000 persons daily until 4 o’clock

Assembly point is the Jewish Hospital at Stawki Street has to be emptied so that the building can be used for the people being resettled.

The Judenrat has to announce the German orders.

Punishments

Any Jew who leaves the ghetto during the resettlement action will be shot

Any Jew who acts against the resettlement will be shot

Any Jew who does not belong to the above mentioned categories and who is discovered after the resettlement action will be shot.

Needless to say the first people deported from the Umschlagplatz at Stawki Street, were from the ghetto prison, the beggars, and the homeless, and old people. The crowds of Jews rounded up in the ghetto were herded to an assembly point – a lot that had been used by the Transferstelle as a corridor of transport to and from the ghetto. In the adjoining yard, which was surrounded by a high fence, was the gutted Czyste hospital, into which the victims were crowded until the freight cars arrived to carry them off to the Treblinka death camp. The Umschlagplatz as this area was called, was guarded by contingents of SS troops, Trawniki men and the Jewish Police, who were under the control of a Jewish Police officer named Mieczylaw Szmerling who had won the German’s confidence for his brutal treatment of the deportees.

On 23 July 1942 one of Höfle’s colleagues Hermann Worthoff visited Czerniakow at the Jewish Councils building to discuss matters, and to increase the daily quota –

The orders are there must be 9,000 by 4 o’clock.

Realising that the Germans intended to exterminate the Jews of Warsaw, Adam Czerniakow committed suicide. Before swallowing the tablet he wrote two notes, one to the Jewish Council executive and the other to his wife. In the first he said that Worthoff had visited him that day and told him the expulsion order applied to children as well. They could not expect him to handover helpless children for destruction. He had therefore decided to put an end to his life. He had asked them not see this as an act of cowardice. “I am powerless, my heart trembles in sorrow and compassion. I can no longer bear all this. My act will show everyone the right thing to do.”

Czerniakow was succeeded by Engineer Marek Lichtenbaum, who was murdered by the Germans in 1943, when the Jewish Council had lost its usefulness. Posters were displayed in the ghetto on 29 July announcing that each person who volunteers for resettlement will be given 3kg of bread and 1kg of marmalade, the Germans knew that many ghetto inhabitants were starving to death, and would report voluntarily. Over the course of this tactic the Germans supplied 180,000 kg of bread and 36,000 kg of marmalade.

On 23 July 1942 the Jewish underground organisations met, but the leaders decided against open resistance, however, members of the Ha-shomer Hatzair organised the distribution of handbills, on the third day of the Aktion and called upon the people – “to revolt, disobey the German orders, explain to people that the way to the Umschlagplatz leads to death.” Ha- shomer hatzair was a radical Jewish youth movement, Mordechai Anielewicz was the leader of the ZOB, with Yitzhak Zuckerman as deputy commander. In the early days confusion as to whether deportation meant forced labour in the East, or death, and the probable Nazi reaction to any armed resistance, initially paralysed the ghetto, but that was to change in the months to come.

During July 1942 the total number of Jews deported from Warsaw was 64,886, which excludes those killed in the ghetto during the round-ups. Until 29 July the round-ups were organised by the Jewish police, afterwards the SS and Trawniki –manner carried out the deportations. The Germans promised total immunity to the Jewish Police force and their relatives, and initially they played a role in the deportation Aktion, but as the Aktion progressed they understood that they were no more than a pliant tool of the Germans and their future like every other Jew was clouded in doubt. They began to desert the ranks of the Jewish Police some were employed as internal guards in the factories, and avoided the morning roll call, where round-ups, were allocated. In response to this the Germans introduced a daily quota, where each policeman was personally ordered to bring in “five heads” a day, and those who did not meet this quota were threatened with having their relatives taken to make up the difference.

In August 1942 the deportations carried on in the same relentless fashion, 130,660 people were deported, amongst those on Friday 7 August 1942, were 200 children from Dr Janusz Korczak’s orphanage. Korczak was the pen-name of Dr Henryk Goldszmid, doctor, writer and renowned educator, who ran the orphanage with his long-term assistant Stefania Wilczynska, and they were both murdered in Treblinka, along with their charges. Korczak was given the opportunity not to be deported, but he chose to remain with the children under his care, as did other heads of orphanages, who stayed with their children, and were murdered at Treblinka. Korczak was at the head of the procession, and Perla Y wrote about the deportation:

The very paving stones wept at the sight of this procession. But the Nazi murderers hit out with their whips and fired shots every few moments. Janusz Korczak holding a child by the hand led the way. With him were the women childminders in white aprons and behind them 200 children, clean and tidy, their hair combed going to their slaughter.

During 19 –21 August the Aktion Reinhardt detachment concentrated on deporting the Jews from nearby towns to the Treblinka death camp, these towns included Otwock, Falencia, Miedzeszyn and Minsk Mazowiecki.From 28 August to 2 September there was another lull in the deportations, because at Treblinka death camp, the operation had broken down. The Commandant Dr Irmfried Eberl, had accepted too many transports, and the inadequate gassing facilities, had meant that transports waited for days, and thousands of corpses had not been buried. Eberl was incompetent and his poor management of the camp, and misjudgement of the camps operation, was to cost him his job, he was sacked by Globocnik who visited the camp in mid- August 1942.

The last phase of the Great Deportation Aktion commenced on 6 September 1942, and its main feature was the comprehensive Selektion that went on till 10 September. All the Jews left in the ghetto on 6 September were ordered to leave their apartments and assemble in a block of streets adjoining the Umschlagplatz. The “shops” and other recognised places of work were allocated quotas of workers, and all those who did not receive a numbered tag were doomed to be sent to the Umschlagplatz – and from there to Treblinka. This lethal Selektion carried out among the throng concentrated in the small area, was dubbed the “cauldron”, Kessel in German, Kesl in Yiddish.

The German quotas allowed for about 35,000 Jews to remain in the ghetto, but the number of Jews some of who remained illegally was 8,000 above this ceiling. The final deportation took place on the Day of Atonement, 21 September 1942, and its victims were the Jewish policemen and their families. The number of Jewish policemen left was 380. The total number of Jews deported from Warsaw to either the death camp at Treblinka, or to a Durchgangslager (Transit Camp) from which they were transferred to labour camps, between the 22 July to the 21 September 1942 was 253,741 according to German statistics.

In early August 1942, the underground organisation of the “Bund” in the Warsaw ghetto sent one of its members Zalman (Zigmunt) Friedrich to follow the trail of the deportees. Friedrich made contact on the Aryan side of the city with a Polish railroad worker, who was familiar with the routes taken by the transports. Friedrich reached Sokolow Podlaski near Treblinka, where he learned about the side track to Treblinka, and he met with Uziel Wallach, who had escaped from Treblinka, who told him the details he had recorded on the death camp.

The description of Treblinka camp published in the Oyf der vakh an underground newspaper, the article was based on this information. Other escapees from Treblinka such as David Nowodworski who returned to the ghetto in late August 1942, were able to confirm on 28 August that resettlement to the East was not for work in the East, but death in the gas chambers of Treblinka death camp.

At the end of October 1942, a consultation was held at the Ha-Shomer Hatzair headquarters at 61 Mila Street and the ZOB (Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa, -Jewish Fighting Organisation) had been consolidated and enlarged with the addition of youth movements and splinter groups of underground political parties of all persuasions from Zionists to Communists. A ZOB command was formed made up of representatives of the founding organisations and the combat groups. At the October 1942 meeting, on the agenda were two key subjects the movement to combat and to point out the likely consequences for collaborating with the Germans, aimed at the Jewish police and workshop owners.

The ZOB leadership were convinced that the ghetto could not effectively resist the Germans, as long as it contained a “Fifth Column”, in their midst, who collaborated with the Germans, passing on vital information. The ZOB’s first operations were directed at the Jewish Police, in retaliation for its diligence and brutality during the mass deportations, and senior officials of the Jewish Council who were known to be close to the SD / Police and Gestapo. The first person condemned to death by the ZOB was Jakob Lejkin, the deputy commander of the Jewish Order Service.The assassination of Lejkin was planned with great care; three members of the Ha-Shomer Hazair, Margalit Landau, Mordechai Grobas followed Lejkin for some time, charting his regular movements and hours of work, whilst Eliyahu Rozanski was chosen as the assassin. Towards the evening on 29 October 1942 Lejkin was shot to death while walking from the police station to his home on Gesia Street. His aide Czaplinski, who was with him, was wounded in the attack. The next attack was directed against Yisrael First, a senior official of the Jewish Council. . First had been one of the Directors of the Economic department, but from the earliest days of the Jewish Council he had acted as a liaison officer between the council and the German Security forces and Police, and he played a part during the deportation action. The assassination of First was carried out on 28 November 1942, by David Schlman of Dror He Halutz, on Muranowska Street.

Another prominent Jewish official of the Jewish Council was Dr Alfred Nossig, who according to Czerniakow, was forced upon the Jewish Council, by express orders of the SS. Nossig according to a neighbour who wrote in her memoirs – “It was no secret that he belonged to the Gestapo and worked for the Germans, and his association with the Germans was even proclaimed on his front door”. He was killed by Zacharia Artstein, Abraham Breier, and Pawel Schwartzstein of Dror He- Halutz in 1943. They were selected for this operation by Yitzhak Zuckermann (ZOB).

Heinrich Himmler the Reichsführer SS visited the Warsaw Ghetto on 9 January 1943, and he wrote to Friedrich Krüger – SS Police Leader East, noting that “40,000 Jews were still living in Warsaw, and 8,000 will be transported out in the coming days”. Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg, the SS Police Leader Warsaw, planned to deport the 8,000 Jews to Treblinka, with the remaining worker Jews being transferred to labour camps in Lublin.According to Polish sources the Germans sent two hundred Gendarmes, eight hundred Latvians and Lithuanians and light tanks into the ghetto. On 20 January, the third day of the Aktion, two SS battalions stationed in Lublin surrounded Többens and Schultz’s shops, commanded by von Sammern, and Theo van Eupen, the Commandant of the Penal Camp at Treblinka, also participated in this operation.

From the first day of the Aktion on 18 January 1943, the ghetto inhabitants were taken by surprise, and many of those captured in the dragnet were the palatzovka workers, who worked outside the ghetto, who were not able to disperse in time. The primary battle in January 1943 took place in the streets, the first group involved was a band of Ha-Shomer Ha-tzair members commanded by Mordechai Anielewicz. Most of the Jewish fighters fell in this battle, Eliyahu Rozanski, who had killed Lejkin, was seriously wounded and died from his wounds. Margalit Landau, who also participated in the Lejkin assassination, likewise fell in battle. Mordechai Anielewicz himself fought until his ammunition ran out,then snatched a gun out of the hands of a German soldier and was saved by the intervention of another quick- witted fighter. Marek Edelman wrote of the incident: The ZOB had its baptism by fire in the first substantial street battle on the corner of Mila and Zamenhofa. We lost the cream of our organisation there.

The Aktion concluded on the 22 January and the total yield was not substantial, and the total removed over the four days, was the equivalent of a single day during the summer Grand Aktion.The Jewish resistance impressed the Poles, the Polish Underground Armia Ludowa, and to a lesser degree Armia Krajowa now provided more aid to the Jewish underground, than in the past. The Jewish underground used the short time they had to consolidate and equip themselves in preparation for the planned uprising.

The ghetto as a whole was engaged in feverish preparations for the expected final liquidation of the ghetto. The general population concentrated on preparing bunkers. Groups of Jews, made up mostly tenants of the same building, went to work on the construction of subterranean bunkers. Shelters such as these had been constructed prior to the January deportation Aktion, and indeed had proved their worth in helping the Jews evade capture. The network of bunkers in the ghetto was expanded and a substantial part of the ghetto population was kept busy at night digging the hideouts and communication trenches under the ground. Much thought and sophistication went into the building of the entrances and exits of the hiding places. Bunks for sleeping were installed, air circulation was provided for, as well as electricity and water. Food and medicines were also stockpiled.

The final liquidation of the Jewish Quarter began on 19 April 1943, the eve of the Passover, and was commanded by Von Sammern. 850 SS, 213 Order Police/ SD and 150 Trawniki-männer entered the ghetto and were met with sustained and determined attacks by the Jewish fighters. This resistance took Von Sammern by surprise, and he had to withdraw the German forces from the ghetto. He was replaced within hours as SSPF Warschau by Jürgen Stroop, SS- Brigadeführer and Generalmajor der Polizei, who was experienced in partisan warfare. Stroop had arrived in Warsaw a few days prior to the final liquidation, after being ordered by Himmler to replace Von Sammern, who according to Himmler was soft hearted

In the first three days, street battles took place in the ghetto. Stroop decided to systematically set fire to the buildings to flush out the fighters. This meant that the Jewish fighters had to abandon their positions and seek refuge in the bunkers. The ghetto was now one great burning torch, enveloped in dense smoke and permeated by stifling odours. The temperatures in the underground bunkers below burning houses reached boiling point and as result most of the food was spoiled. The bunker dwellers had to quench their thirst by drinking warm and fetid water. The Jews refused to surrender to the Germans even though conditions in the underground bunkers were so terrible, breathing was difficult, and under cover of darkness they tried to escape from the burning bunkers to find other bunkers where conditions were better.

On 7 May 1943, the command bunker of the ZOB, at 18 Mila Street was discovered. It was attacked and opened on 8 May 1943, which according to Stroop contained 200 Jews. The command bunker had been attacked using smoke candles and explosives. When the bunker at 18 Mila Street was uncovered, its five exits were blocked, the main entrance was broken open, and canisters of poison gas were thrown inside. Arie Wilner and Lolek Rotblat called on the fighters to take their own lives rather than surrender to the Germans. Some of the fighters did indeed commit suicide while others perished from the the gas, whilst a handful succeeded in taking shelter in one of the alcoves and later escaped via the sewer system to the “Aryan” side of Warsaw. Many of the leaders of the Jewish underground and architects of the last battle for Jewish Warsaw, including Mordechai Anielewicz the ZOB Leader of the revolt, fell in the bunker at 18 Mila Street.On 16 May 1943 Stroop announced that the Großaktion had been completed and ended his daily reports to Kruger in Cracow with the following entries:

The Jewish quarter of Warsaw is no more. The Grand operation terminated at 2015 hours when the Warsaw Synagogue was blown up. Now there are no enterprises left in the former Jewish quarter. Everything of value, the raw materials and machines have been transferred. The buildings and whatever else there was have been destroyed. The only exception is the so called Dzielna Prison of the Security Police, which was exempted from destruction.

Of the total 56,065 Jews apprehended, about 7,000 were destroyed directly in the course of the Großaktion, in the former Jewish quarter. 6929 were destroyed via transport to Tll (Treblinka ll death camp), whilst 15,000 went to KZ Lublin (Majdanek), and other labour camps such as Poniatowa and Trawniki. About 5.000 of the Jews deported to KZ Lublin (Majdanek) were immediately killed in the gas chambers after the initial selection.

Stoop proposed establishing a concentration camp in Warsaw, in order to clear away the ruins, and make use of the bricks, scrap iron and other materials, and indeed a concentration camp was established on the grounds of the former ghetto. Stroop was awarded an Iron Cross Class A by Field- Marshall Keitel, on 18 June 1943, in appreciation of his command over the “Großaktion” in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Krüger requested that a complete set of the daily communiqués, sent by Stroop to himself be sent to Himmler as a momento. Three sets of the report were assembled complete with a selection of photographs, by Stroop himself, one for Himmler, one for Krüger and one was kept by Stroop himself. The report was found at the end of the war by American Forces, and was used as evidence at the International Military Tribunal in Nürnberg, and at Stroop’s own trial in Warsaw.Jürgen Stroop was tried in Dachau by a US Military Court, and was sentenced to death for the shooting of American airmen, but he was extradited to Poland. He was tried in Warsaw in 1951, and he was again sentenced to death, by hanging for war crimes, and was hanged at the former site of the Warsaw Ghetto on 6 March 1952.

Warsaw Images

Warsaw Ghetto Entrance 1941

Warsaw Ghetto Entrance 1941

Warsaw Ghetto - Traffic Control

Warsaw Ghetto - Traffic Control

Warsaw Ghetto - Jewish Cemetery

Jewish men between Jewish Policeman and German soldier

Jewish Men walking in the ghetto

German soldier stops Jewish man at one of the ghetto entrances

Two Jewish children in the Warsaw Ghetto

Two Jewish children in the Warsaw Ghetto

Jewish Market -Warsaw Ghetto

Jewish Market -Warsaw Ghetto

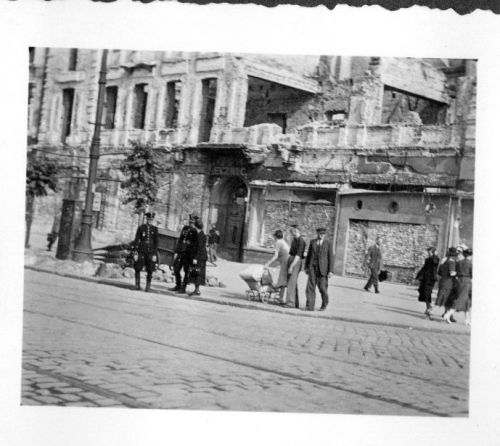

Polish Police in the Warsaw Ghetto

Polish Police in the Warsaw Ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto street scene

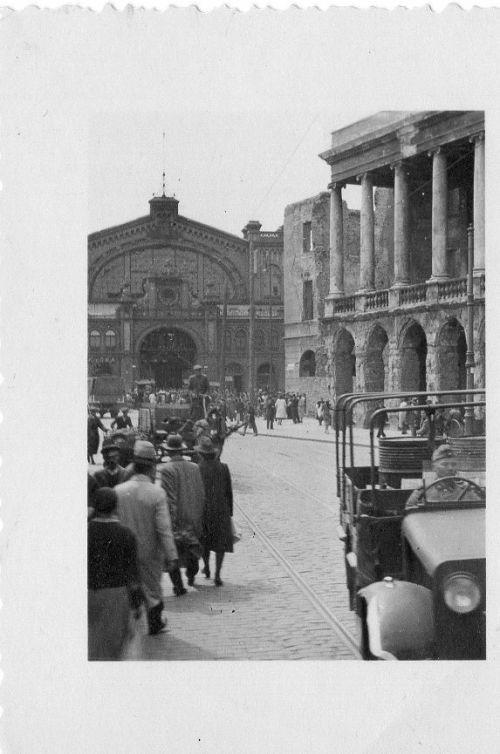

Warsaw Ghetto Markthalle

Warsaw Ghetto Markthalle

SA Official visits Warsaw

Warsaw Ghetto Market

All images - Chris Webb Private Archive

Sources:

Yisrael Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw 1939-43, The Harvester Press, Brighton 1982

The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow, Elephant Paperbacks, Chicago 1999

Abraham Lewin - A Cup of Tears – A Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto

The Stroop Reort, Secker and Warburg Limited 1979

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust

Stanislaw Adler - In the Warsaw Ghetto, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1982

Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto – from the journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum Ed. Michal Grynberg,

Words to Outlive Us – Eyewitness accounts from the Warsaw ghetto. B.Z. I.H.

Photographs - Chris Webb Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society - September 25, 2020