Grodno

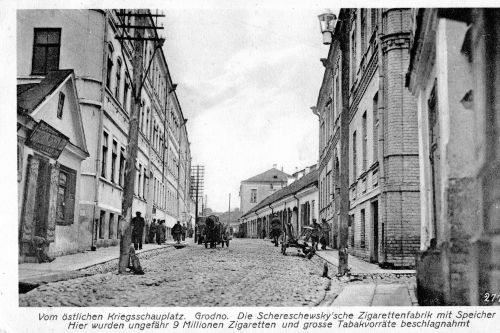

Grodno - German postcard

The city of Grodno is located 80 km north-east of Bialystok. It was the second largest city in the Bialystok district, an area approximately the size of Belgium, and on the eve of the Second World War had a population of approximately 50,000, of whom 21,159 were Jewish. Grodno was a part of Poland between the years 1921, to 1939, and from 1944, until 1991, was part of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia. Today the city is located in the Republic of Belarus.

As a border region between Poles, Lithuanians, Russians and Ukrainians the city was often subject to military attacks, and in 1939, it was occupied by the Germans, but this was short-lived, and the area was taken over by the Soviets, as part of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. When the Germans attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the city was once again occupied by the Germans on the night of June 22 -23, 1941. At first Grodno was not included in the Bialystok district but remained part of the Generalkommissariat Weissrussland, but on September 18, 1941, it was attached to the Bialystok district.

A Gestapo deputy office (Nebenstelle) was set up in Grodno, initially headed by Kriminalsekretar Gross and from December 1941, by Heinz Errelis, who had thirteen men under his command, including his deputy Schott. Gross was in charge of Jewish affairs. Kurt Wiese later became the commandant of Ghetto 1, and Otto Strebelow was the commandant of Ghetto II, and Karl Rinzler was the commandant of the Kielbasin Concentration Camp.

At the end of June 1941, a Jewish Council (Judenrat) was created with an initial membership of ten people headed by David Brawer, the headmaster of a local school. With the occupation the Jews lost all civil rights. Their lives and security were of little or no consequence to the occupiers. In common with other areas occupied by the Germans, severe restrictions and prohibitions were placed upon the Jews of Grodno, including registration, the stamping of the word 'Jude' on their identity cards, and from June 30, 1941, the wearing of an identifying badge. Initially, this was a white armband, with a blue Star of David: a month later the armband was replaced by two large yellow patches worn on the left side of the chest and on the back - left side. Children were exempt from this decree. Although forced labour was introduced immediately after the occupation, this was largely on an improvised basis. However, on October 15, 1941, the first official order was promulgated for the entire district regarding forced labour. It decreed the ages of those who were liable to work - males aged fourteen to sixty and females aged fourteen to fifty-five.

During November 1941, shortly after Grodno was annexed to the Bialystok district, the Jewish inhabitants were resettled to two ghettos, approximately 2 km's apart from each other. As in keeping with the norm regarding the establishment of ghettos, the Jews were concentrated in areas where sanitation, water, electricity and roads, were completely inadequate to meet the occupants needs. The first ghetto (Ghetto I) was established in the city's ancient, central section. Some 15,000 Jews were crammed into an area of less than half a square kilometre. The second ghetto (Ghetto II) was created in the Slobodka suburb, a part of the city which was broader and more open, with fewer houses. Approximately 10,000 Jews were incarcerated in this ghetto. Ghetto II was larger in size than the main ghetto, but more dilapidated. Generally the main ghetto was for the 'productive workers' and Ghetto II was for the 'unproductive' - the sick and the elderly.

The relative quiet that characterised the first year of the ghettos existence enabled the Judenrat to ease the plight of the Jews by creating a very large bureaucratic apparatus, which in itself, became a source of livelihood for many of the ghettos inhabitants. The head of the Judenrat David Brawer considered the supply of food to the ghetto to be one of the Judenrat's major functions. As was usually the case, the affluent enjoyed better conditions and the poor made do with the scraps; the Judenrat were successful, for in Grodno, unlike other ghettos in Poland, no one died of starvation. The occupants of the Grodno ghetto, like their brethren in many other ghettos across Poland, adopted the slogan 'salvation through work.' In other words, nearly everyone believed that as long as the Germans considered the ghetto inhabitants to be a productive force, who were useful to their economy, they would let them live. Factories were therefore created to produce items for the German war effort and to supply the personal needs of the German army and members of the Gestapo personnel stationed in Grodno.

In late 1942, exactly one year after the Jews of Grodno had been herded into the ghetto, the Germans began making preparations for transporting the Jews to the death camps. In the winter of 1942/1943, it was the turn of the Jews in the Bialystok district to face the horrors of deportations. There were approximately 130,000 Jews in 116 localities, including 35,000 in nineteen locations in the Grodno sub-district. The German officials responsible for the transports in the Grodno sub-district were Heinz Errelis, the Chief of the Gestapo in the city, and his deputy Erich Schott.

Transit camps, or as the Germans called them 'Sammellager', which were actually 'collection points' on the way to transportation to the death camps, were set up at various sites in the Bialystok district. The sites for the 'Sammellager' were chosen for their proximity to Jewish places of residence and good rail links. In the case of Grodno, a 'Sammellager' was set up at Kielbasin. From these 'Sammellager' the Jews were transported to Auschwitz Concentration Camp and Treblinka Death Camp. Jews from the Bielski-Podloski sub-district, in the southern part of the district, were sent directly to nearby Treblinka, without passing through a 'Sammellager.' The horrific conditions in the 'collection points' - such as overcrowding, inhuman living quarters, non-existent sanitation, serious food shortages, bitter cold and unspeakable filth - inevitably led to illness and epidemics. The mortality rate was high, and inmates were also subjected to all kinds of harassment, beatings and abuse, and even murder by some of the guards.

On November 2, 1942, both Ghettos I and II were completely sealed off. In the morning the workers from Ghetto II were held up at the gate and suddenly the commandants of the two ghettos, Kurt Wiese (Ghetto I) and Otto Strebelow (Ghetto II) appeared and began shooting at the workers indiscriminately, and 12 Jews were killed, some 40 were wounded, whilst others fled wildly in panic. It was the first time that the Jews of Grodno experienced mass murder, perpetrated without warning. In the evening, the news spread through the city that the Jews from the neighbouring towns had been transported to the Kielbasin camp. The sealing of the two ghettos was accompanied by show-hangings and acts of murder. Punitive executions were not only carried out for Jews trying to escape, but also for anyone caught smuggling food into the ghettos.

Roughly two weeks after the Jews in the neighbouring towns were taken to the Kielbasin 'Samellager' the Germans began liquidating Ghetto II in Grodno. Firstly, however, they transferred those with useful professions from Ghetto II, to Ghetto I. The first deportation from Ghetto II took place on November 15, 1942. The Jews were told that they were being sent away to work, and, according to the testimony of Grodno survivors who reached Bialystok in 1943, the Judenrat and other Jews in the ghetto believed this tale. Therefore, very few tried to hide. The deportees reached Auschwitz Concentration Camp on November 18, 1942, and before they were murdered they were given prepared postcards on which a sentence in German was printed: 'Being treated well, we are working and everything is fine.' They were ordered to sign the postcards and address them to their relatives in Grodno. The first deportation was followed by a brief lull in Ghetto II. But on November 21, 1942, everyone still in the ghetto was deported to Auschwitz. A transport of approximately 2,000 Jewish men, women and children arrived in Auschwitz on November 25, 1942, of which only 433 men and women were admitted into the camp, the rest were gassed.

The first 'aktion' in Ghetto I - the third in Grodno- took place in late November 1942. In the dead of night, men, women and children were removed from their apartments and concentrated in the Great Synagogue. Towards morning Wiese and Strebelow arrived, and ordered the Jews out of the synagogue and began to march them to Kielbasin, under continual beatings. At the front of the column marched a respected Jew Skibelski. The Germans forced him a clown's hat, dance and play the fiddle.

Kielbasin, formerly the farm of a Polish squire, lay 5 kilometres from Grodno, on the road to Kuznica. The Germans converted the farm into a camp for Soviet Prisoners of War. The camp covered one square kilometre, and a double barbed- wire fence surrounded it, with a guard tower at every corner. By the autumn of 1942, it became a concentration camp for Jews, as there were no Soviet Prisoners of War, as they had either been shipped elsewhere or had died. The camp which served as a collection point for the Jews of Grodno and from the surrounding area, it has been estimated that at least 35,000 men, women and children were deported to Kielbasin. Survivors of Kielbasin recalled its commandant, a Rumanian-born German named Karl Rinzler, who could speak Yiddish mixed with German, for his extraordinary brutality. Almost always inebriated, he would take inmates from their huts and shoot them publically for his amusement. In the morning when upon entering the camp, he called over every Jew he encountered and with a heavy rubber club that had a small metal ball attached to its end, beat them until the club was drenched in blood.

The Kielbasin inmates lived in a sort of barracks, 'Ziemlankas' as the camps' inhabitants called them, 50 -100 metres long, 6-8 metres wide, and about 2 metres high - the floor was half-a-metre deep underground. They were the products of the Soviet Prisoners -of-War efforts during the camp's previous incarnation. There were six blocks of these barracks, which were separated from one another by barbed-wire fences. A block consisted of fourteen barracks, each of which held at least 250 to 300 inmates (although Errelis thought that the barracks held 500). The barracks were populated according to different communities / towns and the barracks retained individual locations according to the size of its Jewish population. The floors in these 'Ziemlankas' was just plain earth padded at the bottom with branches and covered with straw. On entering one had to step down five or six steps. Inside there were double-bunks which served for sleeping. Those in the bottom row could sit but not stand up. Those on the top had the roof immediately above them and had to crawl in order to lie down. The boards were dirty, and water leaked in from the roof. Men, women and children lived together in each 'Ziemlankas,' and also shared the toilet -an open pit - for men and women together. The overcrowding, the bitter cold, the rain that leaked in, and the filth and lice turned the 'Ziemlankas,' into death traps. The camp had running water, but Jews were forbidden to go near the taps. It was not uncommon for inmates to be flogged to death for stealing water. Hunger was a permanent fixture at Kielbasin. Food rations consisted of soup with a few un-peeled potatoes or scraps of rotten cauliflower cooked in water and 100 -150 grams of bread per person -though even that miserly bread portion was not distributed every day. All these poor living conditions resulted in lethal epidemics that claimed as many as seventy victims a day on average. Those who fell ill were transferred to separated 'Ziemlankas,' and treated by Jewish physicians and nurses who were also incarcerated in the Kielbasin camp.

But Kielbasin was only a transit camp. A week after the first Jews were imprisoned there, the transports to Auschwitz Concentration Camp began. The order to commence the transports was issued by the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) to Wilhelm Altenloh, head of the Gestapo for the Bialystok district, who relayed it first by telephone and then in writing to Heinz Errelis and to the Gestapo's external station at Grodno. The police and personnel of the Sipo and SD read out the names of the towns, their former inhabitants were then concentrated in the centre of the camp and forced to march to the railway station at Lososna. The elderly and infirm that were unable to keep up with the marchers were shot on the spot. At the station the Jews were packed into freight cars for their final journey. In December 1942, a severe shortage of railway wagons forced the Germans to temporarily suspend deportations to Auschwitz from the Bialystok district. Instead the Germans stepped up the transports to the Treblinka death camp, which was located relatively closer. Towards the end of the month, the Germans decided to liquidate the Kielbasin camp. The last of the Jews there, some 2,000 -3,000 from Druskieniki, Suchowola and Grodno were made to walk to Ghetto I in Grodno. Again a Jew playing a fiddle was placed at the head of the column.

One evening in the second week of December 1942, a transport of approximately 2,000 Jews was brought to Treblinka from Grodno. When the transport entered the camp, most of the inmates had already been locked in their barracks. The deportees were brought to the Transport Square and were ordered to undress and go to the 'baths/ showers.' Some obeyed the order and were taken through the 'Tube' to the gas chambers. Amongst the last who remained in the Transport Square and who had not yet undressed were a few dozen youths. They quickly realised the truth about the true purpose of Treblinka, and some of them began calling out not to listen to the Germans and not to undress. A riot broke out. The Germans opened fire on the crowd. Suddenly there was an explosion. One of the Jewish youths had hidden a grenade and had thrown it in the direction of the shooting. Dozens of Jewish youths who were still in the Transport Square began hitting the Germans and the Ukrainians with their fists and tried to break through the fences and escape. Other deportees from the transport joined them and tried to disperse through the death camp. Some succeeded in breaking through into the living quarters of the Jewish prisoners and sought cover. The SS and Ukrainian -SS recaptured them and returned them to the extermination area, the so-called Upper Camp. Dozens were shot on the spot, as they resisted capture. At the entrance to the gas chamber, some people continued to resist and absolutely refused to enter. The SS and the Ukrainian guards shot into the corridor where the Jews had gathered. Many were killed and the rest were forcibly pushed into the gas chambers. The Germans had been taught a valuable lesson by the Jews from Grodno, for subsequent transports to Treblinka were not received after dark.

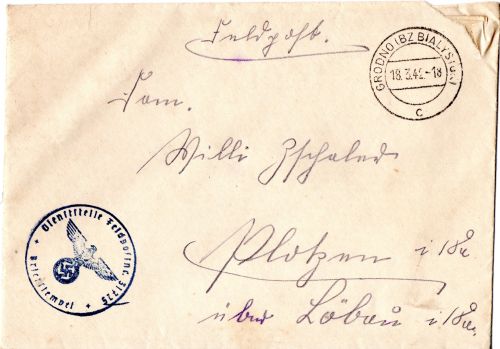

German Envelope from Grodno

The respite in the deportations from the Bialystok district lasted approximately a month, from mid-December 1942 until mid-January 1943. But on January 18, 1943, deportation notices began to be issued. That evening the ghetto's gates were sealed for five days (until January 22) and the Jews were not allowed out. The manhunt began. More than 10,000 people were rounded up and herded into the Great Synagogue. The deportees were marched to the train station at Lososna; only the elderly, the sick and the children were transported there by wagon or truck. Guards were present in large numbers, shooting those who could not keep up. At the train station the deportees were shoved and pushed on top of each other into the cattle cars; the doors were closed and sealed; and they set off on their final journey. During the January 1943, 'Aktion' 11,650 Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. Of these, 9851 were murdered on arrival, while 1,799 were selected for forced labour.

Following the 'Aktion of the Ten Thousand,' approximately 5,000 Jews remained in the ghetto, about half of them 'illegals' (without papers). On February 11, 1943, the Judenrat announced that the Jews were being sent to 'new places of work.' Two days later on February 13, 1943, a few hundred Jews were taken to work outside the ghetto. Shortly after their departure, the ghetto was closed and a new 'Aktion' commenced. Wiese, Strebelow and their cohorts appeared at the ghetto gates, where hundreds of Jews were assembled in the hope they would be taken to work. The Germans started shooting into the crowd. The Jews were then made to line up and marched to the synagogue. Some managed to flee, others were shot trying to make their escape. The members of the Judenrat and its clerks, led by David Brawer, were also herded into the synagogue. At around dusk Brawer was called outside, where Wiese shot him after discovering that two 'Farbindungsmen' - liaison-men of the Judenrat had fled from the ghetto.

A few youngsters tried to break down the doors and windows in the synagogue in order to escape and some Jews tried to hide within the synagogue itself. At 10 p.m. the manhunt was called off and during the night the Jews were made to march to the Lososna train station. During the march there were more escapes. Some were shot to death, but a few dozen did succeed in getting away. The transport left Lososna train station at 5.40 a.m. and reached the Treblinka death camp at ten minutes past noon. Two days later the manhunt resumed.

On the final day of the 'Aktion' on February 16, 1943, members of the Jewish Police went through the streets announcing that anyone caught outside the ghetto would be shot, but that no harm would come to those who assembled at the synagogue. This time though scepticism prevailed and no one came forward. That afternoon the Germans released 200 Jews who were already massed in the synagogue, and declared the 'Aktion' over. Jews emerged from their hiding places and were greeted by the sight of bodies in the street. In the February 'Aktion' more than 4,000 Jews were sent to the Treblinka death camp in two transports - 2,500 in the first and 1,600 in the second - of whom 150 were selected for forced labour. After the two mass 'Aktions,' more than 1,000 Jews still remained in Ghetto I. There was a chronic shortage of food, and anyone caught smuggling food faced certain death.

On March 11, 1943, tension in the ghetto rose to a fever pitch. The next day everyone was ordered into the synagogue. This time though, the Jews did not believe the assurances given by Kurt Wiese, that they were being moved to Bialystok. Most were certain the true destination was the Treblinka death camp. Nevertheless, they remained silent, careful not to antagonise their captors. The assembled Jews, 1,148 people were force-marched from the synagogue to the railway station and crammed into freight cars, approximately 110, to each car. When the transport arrived at Bialystok, the freight cars were opened and the Jews were marched to the Bialystok ghetto. Only now did they realise that indeed their true destination was Bialystok and not certain death in Treblinka.

On March 13, 1943, posters were put up on the city's streets announcing that Grodno was Judenrien (free of Jews). On July 14, 1944, the Red Army liberated Grodno. Approximately fifty Jews who had been in hiding in Grodno and its environs emerged. In more modern terms by the end of 1995, approximately 1,000 Jews lived in Grodno, out a total population of more than 250,000. Of them only 5, were former residents of Grodno residents who survived the Holocaust.

Of the four major war criminals who were involved in the liquidation of the Jews of Grodno and its environs - Heinz Errelis, Kurt Wiese, Otto Strebelow and Karl Rinzler, only Errelis and Wiese were brought to trial. Strebelow was apparently killed in action, and Rinzler, the sadistic commandant of the Kielbasin Sammellager disappeared. Another key figure Schott, the deputy to Errelis committed suicide after the war. Wiese and Errelis were tried in Bielefeld, West Germany during 1966 - 1967. The court acquitted Errelis of charges of direct involvement in murder for lack of evidence. He was found guilty only of complicity in the murder of Grodno's Jews in Ghetto I and of the Jews in the Bialystok ghetto, to which he was posted to, following the liquidation of the Grodno ghettos. The sentences were handed down during April 1967. Heinz Errelis received a sentence of six and a half years in prison and was deprived of West German citizenship for five years. Kurt Wiese was convicted of murder and complicity of murder and received seven consecutive life terms. During 1968, these two men were also tried in Cologne, along with other alleged war criminals who had also been active in Grodno.

Sources

Lost Jewish Worlds: The Communities of Grodno, Lida, Olkieniki, Vishay, published by Yad Vashem

Martin Gilbert, Atlas of the Holocaust, Michael Joseph, London 1982

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor Treblinka, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Judgement in the Cologne Trial of Errelis and Wiese

Photograph: Chris Webb Archive

Envelope: Tall Trees Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018