Oskar Schindler

Oskar Schindler - Krakow 1942

Oskar Schindler was born on 18 April 1908 in Svitavy, a Moravian industrial town, which was part of the Austro-

It was towards the end of 1927 that Schindler first met Emilie Pelzl, born on 22 October 1907, at her parents house in the village of Alt Moletein, in the area of Honeestadt, northern Moravia, some 60 kilometres to the east of Switavy. Oskar’s visit was a business trip with his father to the Pelzl household to sell electrical equipment to Joseph Pelzl, the business calls became more frequent, and a whirlwind courtship developed. Three months later, on the 6 March 1928 against the wishes of both families, they were married. On the very day of the wedding there was a disaster. The local police had received anonymous information that Oskar was already married. He was arrested and detained in the Switavy police cells in order that enquiries could be made.It transpired that Oskar had for some three years been living with a much older woman, a fact that he denied to his new wife. The allegation of bigamy was malicious, but this apart, the facts were correct and this caused Emilie much heartache and she never forgave him.

Schindler started up his own business, running a poultry farm in the village of Ctyricetianu, but gave up after 6 months, unable to make any money. After a short period of unemployment, Schindler worked in Prague, at the Yaroslav Chemnitz Bank. Leaving the bank his last period of serious employment was as a representative for the Company “Opodni Ustev” in Brno, earning between six and ten thousand crowns a month.

Turning back the clock a couple of years, in late December 1936 Oskar Schindler by chance met an old girlfriend whom he had known when a driving instructor in Mahrish Schonberg. She invited Oskar Schindler to a New Year’s celebration party to meet friends whom she said were high ranking officers of the German Wehrmacht. At this party Oskar Schindler was introduced to Wilhelm Canaris, the chief of the Abwehr – German Military Intelligence Service. Oskar Schindler joined the Abwehr on 1 July 1938 having met the Abwehr agent Peter Kreutziger, in the Hotel “Juppebad” in the village of Ziegenhais, on the German side of the Czech/ German border. By 18 July 1938 Oskar Schindler had been arrested and charged with offences against the Czech State, he had recruited a Sudeten German police officer named Prusa, who worked for the Criminal Investigation Department in Brno. Prusa was an alcoholic, in debt and separated from his wife, and it was Prusa who set up a meeting with Schindler at the hotel “Ungar” in Switavy, after having first reported Schindler’s activities to his superiors. The Czech Security Service arrested Oskar Schindler just as Prusa handed over material to him, at the bar in the hotel “Ungar”.

In August 1938 Schindler appeared before the Court in Brno where he pleaded guilty to offences of betrayal against the State – he was sentenced to two years imprisonment. In October 1938 Germany occupied the Sudetenland and all political prisoners were released. Oskar Schindler resumed his Abwehr duties and was posted to Mahrisch Ostrava on the Czech/ Polish border. The Abwehr building in Ostrava shared offices with sections of the Gestapo, SD and Kripo. The head of the Abwehr in M. Ostrava was Karel Gassner, with Schindler as his deputy. Working with Schindler in the field were Alois Girzicky, Ervin Kobiela, Hildegarde Hoheiteva and Hans Vichereek – they were all engaged in collecting and assessing information from a number of sources on the Czech/ Polish border. One of his contacts was Joseph Aue.

The German High Command had opted for the invasion of Poland but, before this could be carried out, some pretext was necessary. This was conceived in the crudest melodramatic terms, and was the work of Himmler and Heydrich for the SD and Muller for the Gestapo and this action was under the command of SS-

At Nuremberg, Naujocks testified:

Muller declared that he had twelve or thirteen condemned criminals who would be dressed in Polish uniforms and left for dead on the spot to show that they had been killed in the course of the attack.

To this end they had to be given fatal injections by a doctor in Heydrich’s service. Later they would also be given genuine wounds inflicted by firearms. After the incident members of the foreign press and other persons were to be taken to the spot. A police report would be made – Muller told me that he had an order from Heydrich telling him to put one of these criminals at my disposal for the Gleiwitz action. The criminal in question, a Pole, was anaesthetised and brought to the radio station where he was then shot. The body was photographed on the spot for the benefit of the Press.

The attack on the station then went ahead – a Polish-

The attack on the radio station at Gleiwitz on 31 August 1939 was Hitler’s excuse to attack Poland and at 4.45am on 1 September 1939 the German battleship ‘Schleswig – Holstein’ opened fire on the Polish Transit Store on Westerplatte.

By 6 September 1939 Krakow was occupied by German units belonging to the 14th Army of the Wehrmacht. General Sigmund List had secured the city, despite fierce opposition from the Polish forces. On arriving in Krakow, Schindler and his team went directly to his apartment on the Westring, formerly called Straszewskiego Street, not far from the Wawel Castle. Schindler had bought the apartment from a wealthy Jew, and its luxurious furnishings included porcelain vases, Persian carpets and heavy velvet curtains.Kobiela, a Trust Administrator suggested to Aue, that he should take over the import/ export business of the Jew Salomon Buchheister at 15 Straddon Street Krakow. Ervin Kobiela took Aue to the premises at Straddon Street where he was introduced as the new administrator. Kobiela ordered the owner, Salomon Buchheister out of the premises. The remainder of the staff were all Jewish who helped Aue to understand the running of the business.The chief accountant at the firm was Itzhak Stern who had worked for Salomon Buchheister since 1924. Aue immediately re-

With most of the Krakow Trust Administrators also in the pay of the Abwehr, Schindler had little difficulty in concluding the transaction, and within a few months had brought the factory outright for a reported sum of 300 Reichsmarks. The previous owner of ‘Rekord’ Abraham Bankier, was surprised when Schindler invited him to help in setting up the factory for producing enamelware. The factory was renamed ‘Deutsche EmailwarenFabrik’ – The German Enamel Works, known as Emalia. During Schindler’s first year at Emalia he employed about seventy Polish workers, which included only seven Jews. The balance gradually changed, and he was employing more Jews as time went on. Jews were cheaper to employ than Poles, and this was the primary reason for employing them, this was an advantage not only to the factory, but to the Jews as well, as they were able to possess the protection of the ‘Kennkarte’, followed very quickly by the ‘Blauschein’ , an endorsement of the ‘Kennkarte’.

On 3 March 1941 Governor Wachter published an order for a “Jewish Residence Zone” – the Jews had to move into this zone. This zone was situated on the right bank of the Vistula in the Podgorze district. Using Jewish labour, the Germans erected a wall surrounding the Ghetto, installed security posts and constructed gates. The main gate was at Podgorze Square, there were other gates at Limanowska Street and at Plac Zgody. About 15,000 Jews were transferred from the city into the ghetto, a further 2,500 lived outside the ghetto, either in the orphanage, a residential home for the elderly or huts at the ‘Optima’ factory. During the spring of 1941 Schindler returned to Svitavy to see his father who was now in bad health. He intended to patch up past differences between them. To some degree he was successful and when he left they had mutually agreed to bury the past and look to the future. Schindler’s return to Krakow went via Mahrisch Ostrava to see his wife who was still living in the apartment provided by the Abwehr.

In Krakow Schindler was visited by representatives of the Armaments Inspectorate – Emalia was to take on armaments work. Another blow to Schindler was that all wages to his Jewish workers would now be terminated and alternative payments pro-

Julius Madritsch was born on 4 August 1906 in Vienna, a pacifist by nature was drafted into the Wehrmacht, and he did his utmost to be discharged. He was invited to move to the General Gouvernement to become a purchasing agent for the Wehrmacht, he was also appointed a “Trust Administrator” of two textile plants in Krakow. One of Madritsch’s eager and ardent accomplices was Raimund Titsch, the travelling manager for Madritsch, who visited Bochnia and Tarnów to ensure that Madritsch workers were cared for.

In June and October 1942, the Nazis carried out the partial liquidation of the Krakow ghetto, during the final days of May 1942 the Ghetto was surrounded and sealed during the night by a strong cordon of Sonderdienst. On the morning of the 2 June 1942, the deportations commenced and it became a familiar sight in the ghetto to see Jewish policemen led by SS storm –troopers brining the Jews from their homes to the gathering point in the Optima factory yard and from there to the freight station at Prokocim. The first to be expelled were the old people, women and young children, those that were not murdered on the spot, were transported to Belzec and gassed. The Germans were not satisfied with the number deported – they assumed that many who did not have stamps on their passes did not report. Thus during the nights of 3 and 4 June 1942, the Gestapo, Sonderdienst and Jewish Ordnungsdienst inspected papers, stopped and searched Jews in the streets, entered hospitals and dwellings.This time several thousand Jews were marched to the Plac Zgody – the round-

During meetings with the Judenrat in the ghetto to discuss ways of relieving the employment situation and one of the solutions proposed by Madritsch was to employ more Jews per sewing machine and to open up further factories in the towns of Bochnia and Tarnów, thus giving hope to a further 2,000 Jews under the cover of essential armaments contracts. His first priority was to change the status of his factories to ‘armaments factories’ and thus receive the protection, like Schindler, of the Armaments Inspectorate. The Madritsch enterprises in Krakow-

Emalia ‘s production was continuing, but elsewhere in Krakow there was turmoil and panic. The seizure of Jews on the streets continued, Mrs Edith Kerner, who worked in the offices of Emalia was beside herself having seen fourteen Emalia workers seized by the SS in the street and arbitrarily added to a transport to be taken to Prokocim freight station. Among those seized was Abraham Bankier, Schindler’s trusted factory manager. Mrs Kerner tried to contact Schindler at all his known haunts, and after some hours she managed to speak to him. Schindler drove directly to the railway station – he patrolled the platform, shouting for Bankier. The wagons had been in the sidings all day, the occupants sealed in with no food or water. The SS officer in charge relented under pressure from Schindler and released Bankier and the other workers from the transport against receipt. The Emalia workers had simply forgotten to attend the Jewish Labour office to obtain their new “blue” work permits. Three of the fourteen were Szulim Lesser, Jerzy Reich and Abraham Bankier

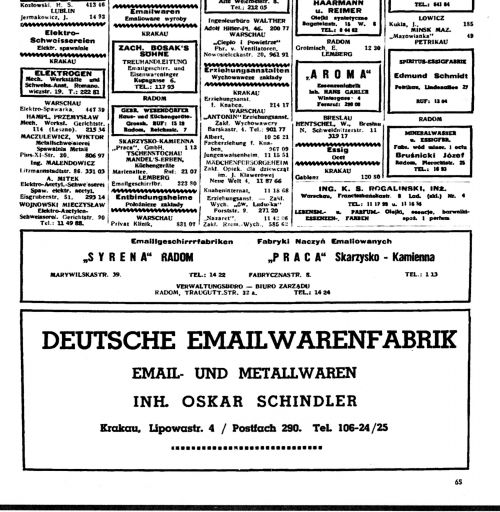

Schindler's Emailia - Entry in 1942 Telephone Directory for the GG

On 28 October 1942 another 5,000 Jews were deported from the ghetto, leaving 14,000 inside. In December 1942, the German’s ordered the ghetto to be divided into two parts-

It was suggested that Schindler by his Abwehr boss that he should make a trip to Budapest to meet with the Jewish Relief Organisation, and pass on the true nature of the extermination of the Jews in Poland. First hand knowledge was essential as the information coming out of Poland was unbelievable to the Jewish agencies. Schindler in his position as an Abwehr agent was the holder of a special passport which enabled him to travel within and outside of the Reich. Usually he would drive his Horch motor car across borders, but on this occasion, he was smuggled across the borders in the back of a newspaper van. In Budapest he was to meet with Samual Springman and Rudolf Kastner, members of the Zionist rescue organisations and leading figures in the Jewish Relief Organisations. He handed to Springman and his associates, evidence of the Jewish transports to the death camps and the cruelty inflicted on the Jews of Poland. After his report, the Zionists in Budapest trusted Schindler enough to ask him to transmit money for the rescue of Jews to the Zionists in Krakow, and to enlist his long term co-

Amon Leopold Göth was born on 11 December 1908 in Vienna. He was married twice, divorced in 1934, and again in 1944. He had two children.

Göth joined the staff of SS-

Schindler was to meet Amon Göth at the newly constructed Commandant’s villa ‘Rotes Haus’ (Red Villa), occupied by Göth and his mistress Ruth Kalder. This informal dinner party was attended by all the bosses from the establishment, the Armaments and supply factories, Security and Police chiefs. In early January 1943, Schindler astutely read the situation that the Jews were destined for disaster. Many of his workers had been taken to Plaszow labour camp which entailed a daily march from the camp to the ‘Emalia’ works escorted by the Ukrainian guards. Schindler bought a plot of land which was adjacent to his factory from a young Polish couple. Through his contacts with the Armaments Inspectorate, he acquired the necessary permission to build barracks within the ‘Emalia’ complex. He then applied to the SS offices at 2 Pomorska Street, Krakow for planning permission to construct the barracks in accordance with regulations. Site meetings were called and final approval came from the SS bureaucracy and from Amon Göth , for the release of the Plaszow prisoners to the Schindler factory barracks. Göth supported Schindler’s plans and facilitated the project by supplying experts from the Plaszow camp to work on the newly constructed barracks. Adam Guard, a young engineer was transferred by Göth from Plaszow to the new building project at the Schindler’s works.In the new Schindler barracks were installed kitchens, a laundry and even showers. These new facilities were questioned by the SS, but Schindler just mentioned the control of typhus and lice, and that was the end of any material challenge. It cannot be repeated too often that his factory became a haven for Jews, in which Schindler sheltered many who were old and weak and therefore inefficient workers. By saving his workers from daily harassment, he increased their efficiency and thereby the output of his factory and profits. But it is equally evident that his compassion often outweighed his profit motive. Schindler took advantage of the rivalries between the Armaments Inspectorate, the Gestapo, and the SS, since he knew the Armaments Inspectorate was likely to support any scheme that would add to the difficulties of the SS.

On direct orders from Heinrich Himmler the Reichsführer-

During the evacuation of Ghetto A, many people tried to escape, but were shot on the spot and left lying in the road. Others had devised clever escape methods, by lifting off the covers to the main sewers that crossed under the streets of Podgorze, and disappearing into the stinking waste and crawling to the outlet on the Vistula. This was the way of escape of Dr. Julian Aleksandrowicz, with his wife and small son. There were two main escapes into the sewers, one at the junction of Jozefinska and Krakusa streets, and the other at the crossing of Jozefinska and Wegierska Street. Many escaped this way until the SS detected this, waited at the outlets, and shot the escapees.

Now it was the turn of Ghetto B.

At dawn on the 14 March 1943 the Sonderdienst – Volksdeutsche special service forces, as well as Trawniki –Manner, and the Polish ‘Blue’ police surrounded the Ghetto.

People in the Ghetto were running in all directions, there was absolute panic. People, were shouting, crying, loaded down with possessions, looking for sanctuary, where there was none. Then there was utter silence and all those in the area froze, their eyes turned towards Targowa Street. Standing, dressed in a black leather coat, holding a riding crop in one hand and a short automatic rifle in the other, accompanied by two large dogs called Rolph and Ralph stood Amon Göth, surrounded by his personal bodyguard. Other dignitaries arrived and selected their favourites, their informants and selected personnel who were not to be subjected to the liquidation that was to follow. The Germans had killed within a few hours, approximately 1,500 persons and a further 3,000 were transported to Auschwitz. The ‘Sauberungskolonne’ – Cleaning up teams – worked in the ghetto until December 1943, selecting and storing objects, furniture and equipment etc, left behind. The ghetto enclosure was then taken down and the area reverted to dwellings for the Polish inhabitants of Podgorze. The final act in the destruction of the Krakow Ghetto was on the 14 and 15 December 1943. In the early evening, truckloads of helmeted and armed SS, under the direct command of Amon Göth, surrounded the Ordnungsdienst building. All members of the Ordnungsdienst, with their families were loaded onto trucks, driven away and executed in Plaszow. The newly erected barracks at ‘Emalia’ were a great success. No longer did the ‘Schindler Jews’ have to march the 3 kilometres from the Plaszow camp to the Emalia factory, and endure the harshness of the discipline in Plaszow. The punishments of 25 lashes disappeared, the persistent parading, and the fear of the evil-

In accordance with requirements, Schindler’s sub-

In August 1944, the order came from the Director of Armaments for the disbandment of Schindler’s factory and for all its Jewish workers to be taken to KL Plaszow. There were now about a thousand Jews working in Emalia, three hundred were to remain for the dismantling of the plant, the remainder would be sent to KL Plaszow, for relocation. The men were to be sent to KL Gross Rosen, the women to KL Auschwitz, at Gross Rosen there was a vast quarry, managed by the SS, with the name the “German Earth and Stone Works”. The 700 “Schindler Jews” marched out of Emalia for the last time – they were going into the unknown of KL Plaszow – the 300 that remained were bona-

On the 17 August 1944 Emalia awoke to a mighty explosion, barracks were on fire and secondary explosions were erupting all over the area. An Allied forces Liberator bomber had crashed on the Emalia sub-

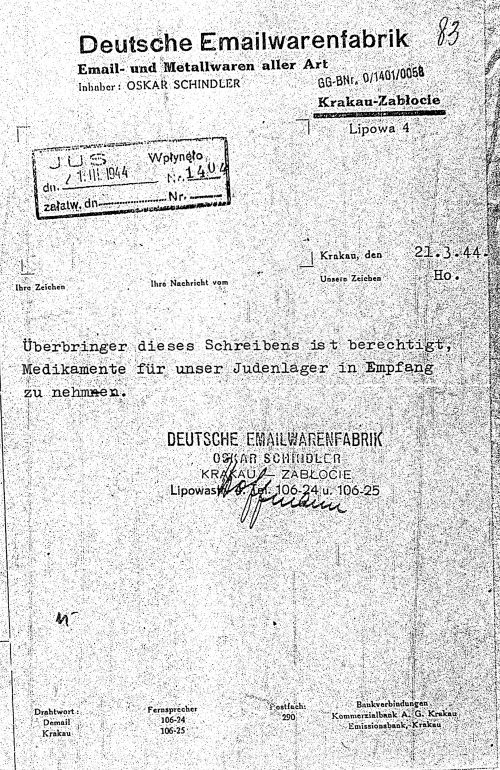

Letter from Emalia to the JUS -21 March 1944

Schindler was now looking for new territories where he could transfer his machinery. He went to Berlin where he sought the assistance of Colonel Erich Lange, Chief of Staff of the Armaments Inspectorate at Army Headquarters. He was passed from department to department but eventually he acquired the authority to transfer the plant at much personal cost. We have arrived at the crucial period of Schindler’s activities; he had amassed a great personal wealth and a guarantee of safety out of the Reich to Switzerland. He thought long and hard of his circumstances, his wife and the people that looked to him as their only chance, their last chance. This was not a game, this was not now a money-

Schindler was to occupy part of the ‘Brueder Hoffmann’ spinning mill. Herr Hoffmann, a former Trustee of this mill and well decorated with Party protectionism, made the move very difficult for Schindler. The move from Krakow to Brunnlitz was a costly business, and made a significant dent in Schindler’s accrued fortune. Then there were the usual inducements to the bureaucrats, personally delivering luxuries to keep the “Gentlemen” in a good and co-

With Schindler’s commitment to the new factory in Brunnlitz he handed over the compilation of the ‘list’ to the Jewish Labour Office in KL Plaszow, which at the time was administered by SS-

The ‘list’, meanwhile had passed into the hands of Goldberg who was now the sole arbiter and chose to use his authority and power to make himself a very rich man. On 15 October 1944 at 5 a.m. on the Appellplatz the list of workers going to Brunnlitz was read out, the men and boys were transferred to Brunnlitz, via the KL Gross Rosen. In October 1944 the 300 ‘Schindler women’ together with the children Bronislaw Horowicz, Celina Carp, Ewa Ratz, and Halina Horowicz left KL Plaszow in sealed wagons on route to Schindler’s factory in Brunnlitz. After some hours, the transport arrived at Auschwitz-

Again there were phone calls to friends in high places. The emissary to be sent to Auschwitz to accomplish this task was a young trusted female associate of Emilie Schindler, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist in Switavy. The release was accomplished with little difficulty but not without incident. The list of the women to be released to Brunnlitz did not agree with the list held in the administration office in Auschwitz.The women all marked with red paint, to deter escapes from the camp, were marched to the transport destined for Brunnlitz. At the point of departure there was a remarkable coincidence. Working on the other side of the wire were some of the ‘Schindler men and boys’ who had been sent to Auschwitz from Brunnlitz. Manci Rosner, Regina Horowitz with her daughter Niusia had seen their families working in the men’s compound. There was a short personal contact before the transport departed for Brunnlitz. The women’s ordeal was over – only two women were missing – one of those was the mother of Itzhak Stern. Richard Horowitz was later re-

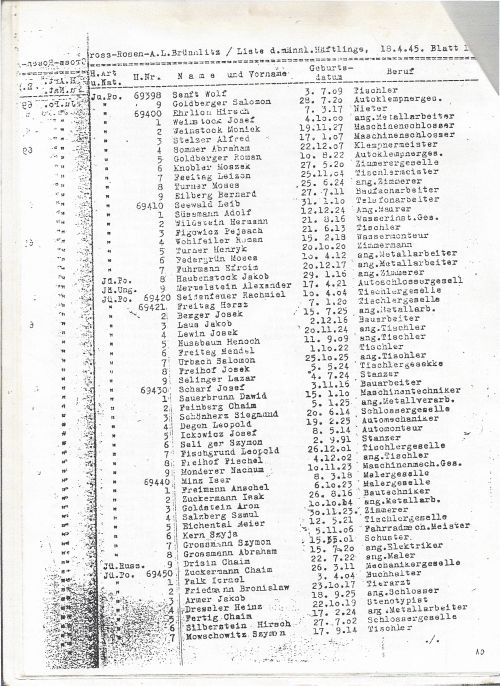

A page from Schindler's List - Gross Rosen to Brunnlitz (Courtesy of Tali Nates)

In the middle of the month 120 quarry workers from Golleschau were put into two cattle cars, the train left Golleschau, heading West away from the advancing Soviet army. The first point of call was at Auschwitz – Birkenau, where utter panic ensued, the transport continued on calling at Cieszyn, Oderberg, Schonbrunn, Freudenthal, Switavy and finally Brunnlitz. They travelled for more than 10 days without food or water. The doors on the cattle cars were not only locked but frozen shut, for it was bitterly cold. Eventually the cars were uncoupled and abandoned in the rail yards of Switavy. Schindler received a phone call from a friend at the depot had heard moans coming from inside the wagons. Schindler told him to arrange for the cars to be shunted to the sidings in Brunnlitz – this was done, it is almost impossible to describe what the Brunnlitz prisoners saw, when they finally succeeded in opening the doors of the two cars. The transport arrived in Brunnlitz on the 30 January 1945.

In each car there was a pyramid of frozen corpses, their limbs madly contorted occupied the centre. The 100 or more still living were seared black by the cold and looked skeletal in appearance. The fight to save the lives of the deportees from Golleschau was supervised by Mrs Schindler. Moshe Bejski speaks of Mrs Schindler’s ‘special porridge’ that was considered by many to have been the major factor in saving the lives of the survivors from Golleschau. The factory produced shells for the German Army for seven months. In all that time not one useable shell was produced, not one shell passed the quality tests performed by the military. Instead, false military travel passes and ration cards were produced, as well as the collection of Nazi uniforms, weapons and ammunition. Schindler in his tireless manner succeeded during these months in persuading the SS to send a further 100 Belgian, Dutch and Hungarian Jews to his factory camp in Brunnlitz, in order to prolong war production, on behalf of the crumbling Third Reich. The Brunnlitz camp, a sub-

Leipold a hairdresser before the war, was a stereotype Nazi who had commanded the Labour Camp at Budzyn, in Poland, and who had a brutal reputation, and he tried to run Brunnlitz with a rod of steel, only to be frustrated at every turn by Schindler. Schindler constantly challenged his authority – only a few weeks after the Golleschau incident, one of the survivors Edek Elsner, was ordered by an SS guard to move a box.

Elsner replied “The box weighs 35 kilograms, and I weigh only 32 kilograms – how can I carry the box?”

On the evening 8 May 1945, Schindler spoke to the entire camp, including the SS guards and the Commandant. They listened together to a speech by Winston Churchill which was being broadcast about the surrender of Nazi Germany. After Churchill’s message had got through to those present, there was general euphoria, Schindler then gave a speech to thank everyone for their trust and help in the most difficult of circumstances. Schindler orgainised a home defence of the entire camp and factory, all the arms had been issued and they prepared themselves for any situation. Wehrmacht vehicles were passing on the road at the entrance to the factory. The whole camp was split up into feverish activity.

Mr and Mrs Schindler were preparing their escape to the West with the help of a chosen few Jews who would escort them. The Jewish prisoners who had come to Brunnlitz from Budzyn were out to settle old scores. They selected Kapo Willi, the most hated Kapo in the camp, who had been with them in Budzyn. Willi had been responsible for the death of a number of Jewish prisoners in Budzyn, he was seized and strung up on a factory girder, where he died. The elderly Simon Jereth from the box factory adjacent to Emalia, took out his false teeth and from the gold fillings Hersch Licht, crafted a ring out of the gold. On the inner circle of the ring, they inscribed a simple ‘thank you’.

Richard Rechin volunteered to drive the lorry that was to escort the Schindler’s towards the American lines. The bodyguard of young Jews were Richard Rechin, Zew Schanz, Adolf Gruhaut, Sadek Wilk, Leopold Dagen, Estera Pincas. The Schindler’s were to leave, in their car, a two seater Horch. They took with them Schindler’s woman friend Marta with them. One of the last acts Schindler was to discharge and share with his Jewish workers was the issue to each and every one of them a length of cloth from the spinning mill textile store. Stern and Salpeter dished out vodka and cigarettes, considered by Schindler, as a ‘first aid’ package. Last farewells offered, the Schindler group left in convoy.

Oskar Schindler dressed as a Jewish prisoner and in possession of his ring, reference documents written in Hebrew and one large diamond which he concealed in the front seat of his car, their journey took them through the panic of the retreating Germans and the partisans who were controlling the roads. Stopped by a Russian patrol they were stripped of their watches, at a later check point where they stayed overnight, they lost all their property and their vehicles were damaged beyond repair. Near the village of Elanorenhaim they came across an American military outpost where they were detained. The Americans believing they were escaping Nazis took them into custody.

Lt Kurt Klein himself a German born Jew listened to their story and inspected their references that Schindler showed them. Another batch of American army officers arrived on the scene. Among this group were several Jewish soldiers and a Rabbi. There was no doubt now, when the unbelievable story began to unravel. For the Schindler group, the nightmare was over During the last days of World War Two Schindler fled to Germany, without any money. As for Amon Göth he was tried by the Poles in Krakow and after being found guilty of mass murder in clearing a number of ghettos and murders in Plaszow he was hanged on 13 September 1946.In 1949 he received money from a Jewish – American charity and emigrated to Argentina, with his wife and current mistress, and some of his Jewish friends but his move was not a success, his skills as a farmer, were not as good as his skills of a rescuer. In 1958 Schindler returned to Germany alone and established a cement factory that went bankrupt.

In 1961 Schindler went to Israel for the first time, and there his fortunes improved, he was warmly welcomed by the Jews and feted as a hero, by the people he rescued. His yearly visits became an annual event, he loved receptions and he loved to have everyone around him. Schindler was honoured on his birthday in 1962 when Yad Vashem declared him as Righteous and Schindler planted a tree, to mark the award. Schindler lived in poverty for 11 months of the year opposite Frankfurt station in a one room apartment, he lived off a small pension and handouts form Jewish survivors. In the autumn of 1964 he was filmed by German television and was asked why he had intervened on behalf of the Krakow Jews? :

Schindler said:

The persecution of the Jews in the General Gouvernment in Poland meant that we could see horror emerging gradually in many ways. In 1939 they were forced to wear the Jewish Stars and people were herded and shut up in ghettoes. Then in the years 1941 and 1942 there was plenty of public evidence of pure sadism, with people behaving like pigs, I felt the Jews were being destroyed. I had to help them. There was no choice.

Oskar Schindler died on 9 October 1974 in Hildesheim, Germany. He was buried in the Catholic Churchyard on Mount Zion, Jerusalem. On 24 June 1993, Emilie Schindler was also honoured like her former husband. She died on 5 October 2001, aged 94 years. She lived for 50 years in a little house 40 kilometres South West of Buenos Aires.

Sources

Dr. Robin O'Neil- Unpublished Draft 'Oskar Schindler - Stepping Stone to Life'

Photograph courtesy of Dr Robin O’Neil

Emalia Letter - Yad Vashem Archives

Telephone Directory - Holocaust Historical Society

Extract of Schindler's List courtesy of Tali Nates (Johannesburg Holocaust Centre)

Thanks to Georg Biemann

© Robin O’Neil and Chris Webb, Holocaust Historical Society, February 16, 2022