Lvov (Lemberg)

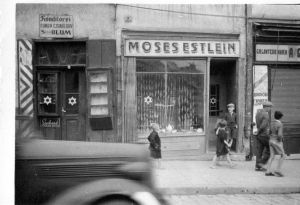

Lemberg - Jewish Shops (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Until the First World War, Lvov was the capital of eastern Galicia, a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During the nineteenth century, the city became the centre of the Enlightenment movement of eastern European Jewry. Where in the neighbouring rural towns most of the Jewish population was Hasidic, Lvov had a significant number of Polish and German speaking Jews. Following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War One and the Polish occupation of the area on 22 November 1918, the Jews of Lvov were targeted in a pogrom in which hundreds of people were wounded and approximately 100 were murdered. In subsequent years, Jewish relief organisations worked prodigiously to rehabilitate the community.

In the interwar period, Lvov was a centre of political activity, in which various parties and movements operated, including the Bund, Agudath Israel, and Zionist parties and youth movements. A number of Jews were also members of the Polish Communist Party, Jewish political parties in the city also sponsored assorted social activities. The economic situation of the Jews of Lvov began to deteriorate during this period; many required support and were aided by Jewish self-help institutions and free-loan funds. The community had several savings and loan associations and Jewish trade unions. Although most Jewish children attended Polish public schools, also available was a wide range of Jewish educational institutions that taught in Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew: pre-schools, kindergartens, and Orthodox, Zionist, and Yiddish elementary schools; vocational schools and several high schools. Lvov was an important centre of Jewish journalism and several Jewish sports associations operated in the city. The Soviet Red Army occupied Lvov on 20 September 1939, at this point in time Lvov was the third largest city in Poland after Warsaw and Lodz, and was home to approximately 100,000 Jews, most of whom were merchants, manufacturers and artisans. As the German Blitzkrieg tore through Poland, tens of thousands of Jewish refugees from elsewhere in Poland, descended on the city, swelling its Jewish population to 200,000. After the Soviet occupation, private economic enterprises and property ownership were abolished, and most manufacturing became state-run. Jewish community institutions were closed; only in synagogues were Jews officially allowed to hold public assemblies. Schools were run on Soviet lines and Jewish political parties and youth movements were disbanded. In late June and early July 1940, the Soviet authorities deported thousands of Jews to the Soviet interior, as they doubted their loyalty to the Soviet regime. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Jews fled eastward from Lvov, as the Red Army retreated, and by the time the Germans occupied Lvov, an estimated 160,000 Jews remained in the city. The German forces entered Lvov on 29 June 1941 and began to persecute the Jews immediately. Several thousand Jews were murdered in pogroms in July and August 1941. Right from the start of the German occupation, the Jews suffered terribly from pogroms. One such pogrom was known as the 'Prison Aktion,' which was instigated by a rumour that Bolsheviks and Jews had murdered political prisoners in the city's prisons, before the departure of the Red Army. Local Ukrainians were the main perpetrators of the abduction and murder in the streets of at least 4,000 Jews. The Ukrainians were encouraged and supervised by a German Einsatzgruppen unit under the command of Guenther Hermann. Murders of Jews in Lvov continued throughout July 1941, peaking on 25-27 July 1941, when the Ukrainians killed approximately 2,000 Jews in a pogrom known as the 'Petliura Days,' after the Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura. On 15 July 1941, the Jews of Lvov came under sanctions, including the compulsory affixing of a Jewish patch to their clothing and restrictions on movement. On 22 July 1941, the Ukrainian mayor, Georg Polanskyi, and the German military authorities issued an order concerning the formation of a provisional committee for the Jewish community. After several Jewish public figures refused to chair the committee, Yosef Parnas, a well-known lawyer and a former Austrian army officer, was selected for this position.

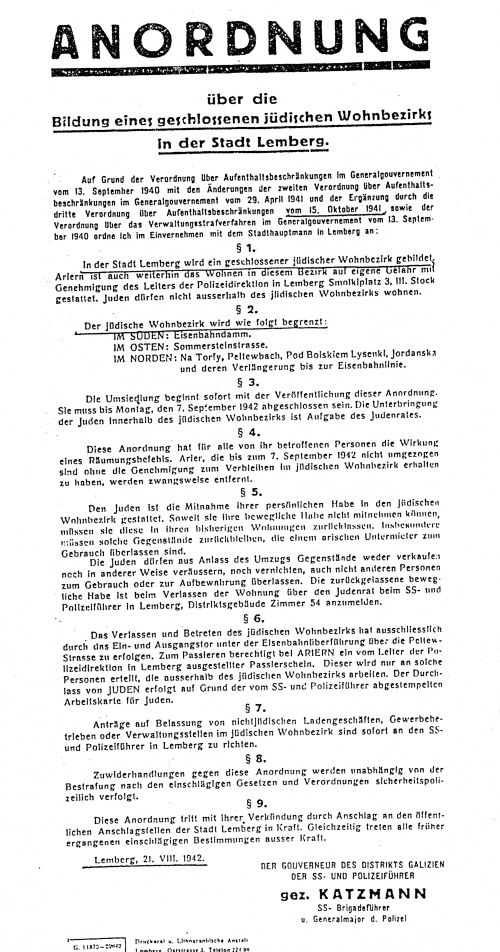

On 1 August 1941, the German authorities announced the annexation of eastern Galicia to the Generalgouvernement. In the aftermath of this development, the provisional committee officially became a Judenrat and its membership was increased. In August 1941, the Judenrat established the organisational structure of its roughly 1,000 employees; the number increased to approximately 4,000 in 1942, and continued to rise thereafter. Twenty-three departments operated within the organisation, among them a labour department, which mainly was responsible for supplying Jews for forced labour, a housing department, a supply department, and a welfare department. In early August 1941, about 1,000 Jews, including community leaders were taken hostage and the community was given ten days to pay a ransom of twenty million rubles. The sum was raised with great difficulty, but the hostages vanished without trace, and were probably murdered. In September 1941, the commander of the Jewish Order Service in Warsaw, Jozef Szerynski, was brought to Lvov to set up a similar organisation in the city. Within two months, the force grew to approximately 500 members. Parnas held his post as chairman of the Judenrat until the end of October 1941, when he was executed for refusing to supply 500 Jews for forced labour. His deputy, Adolf Rotfeld, chaired the council until his death in February 1942, when Henryk Landsberg, a lawyer and public figure, took up the position. The Judenrat was unable to develop educational and cultural enterprises under official auspices, but Jewish youngsters organised unofficially in private homes to continue with their studies. Youth movements also held clandestine cultural activities. A group of historians, among them Jakob Schall, collected material and began to write a chronicle of Jewish history in the city during the German occupation, but the material they gathered was lost when Schall was murdered during a German aktion in August 1942. On instructions from Karl Lasch, the German governor of Galicia, the establishment of a Jewish residential quarter was issued on 15 November 1941; Jews were given one months notice to move into the newly designated area. The quarter selected at mayor Polanskyi's insistence, was set up in two slums far from the city centre, in the northern part of the city, in an area known as Zamarstynow. Jews were allowed access to reach the ghetto under the railway bridge on Peltewna Street. The Germans carried out a number of selections there, where they shot and abused Jews, in what was known as the so-called 'Todesbrueckenaktion' Death Under the Bridge Aktion'. Some 5,000 Jews were exterminated in this 'Aktion' which was conducted by the municipal authorities in collaboration with German police units under the command of Albert Ulrich. Thousands more were murdered in subsequent 'Aktions' that continued through mid-December 1941 and during the same time the Germans began to deport large numbers of Jews to labour camps in the vicinity, with large numbers taken to the Janowska Street camp, which was located on 134 Janowska Road, in the suburbs of Lvov.

Official Notification of the Creation of Jewish Living District (Wiener Library)

In March 1942, the German police chief Ullrich ordered the Judenrat to prepare a list of 20,000 unemployed and what he described as 'asocial Jews' who the Germans claimed were to be resettled in the east. The Jews debated among themselves whether to co-operate. A delegation of four rabbis led by Rabbi David Kahana, visited the Judenrat to dissuade the leadership from drafting the list. Eventually, the chairman of the Judenrat was forced to produce the list. When the murder operation began on 19 March 1942, Judenrat officials and members of the Jewish Order Service began arresting Jews who lived on welfare and those without labour permits and turned them over to the Germans. At the end of March, as the number of Jews handed over did not meet the quota, the Germans took over the administration of the operation, placing Ullrich in charge and mobilising Ukrainians to participate. They completed the operation on 1 April 1942, the eve of Passover, by abducting Jews from their homes as they conducted the Seder service. In all some 15,000 Jews, were transported in cattle cars from the Kleparow station to the Belzec death camp. A census of the Jewish population of Lvov was carried out after the murder operation of March –April 1942, with the first mass deportation of Jews to Belzec death camp. Workers in essential positions were given special armbands marked with the letter 'A.' During this period the Jews of Lvov strove to save themselves by means of forged papers. Most of those who obtained such documents attempted to leave the city. Many of those who were unable to escape prepared hideouts, some even sought refuge in the city's underground sewer system. In the weeks following the first mass deportations the Germans attempted to concentrate all of Lvov's Jews in one place whilst reducing the size of the Jewish quarter.

A memorandum dated 22 April 1942 indicated that some 10,000 'Aryans' were still living in the area designated for the ghetto, while approximately 15,000 Jews remained outside it. Meanwhile the murder operations continued unabated, for example on 20 May 1942 all Jewish veterinarians in the city were rounded up and taken to the Janowska camp, where they were all murdered. Also on 24-25 June 1942, a special SS unit under the command of the head of the Lvov Gestapo, Erich Engels, stormed the Jewish quarter and within a few hours, 2,000 Jews were arrested and taken to the Janowska camp. After a selection was held, 130 were assigned to forced labour, the remaining Jews were murdered in the 'Sands', the Piaski sand dunes, behind the forced labour camp.

The second mass deportation of the Jews of Lvov commenced on 10 August 1942 and it continued until 23 August 1942, this 'Aktion' was directed and supervised by the SS and Police Leader of the Lvov district SS- Gruppenfuhrer Fritz Katzmann along with his subordinate Erich Engels, who held the position of head of Jewish Affairs (Judenreferent) for the Lvov Gestapo, under the leadership of Kurt Stawizki. Thousands of Jews were arrested every day and taken to Janowska camp, where SS officers under the command of Ernst Inquart performed selections and sent the vast majority to Belzec death camp, in cattle cars from the Kleparow railway station. Many Jews tied to escape deportation by hiding in the ghetto, but in most cases the Germans discovered their hideouts. In all some 50,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp, where they were murdered. Following the termination of the second mass deportation to Belzec on the following day, the 24 August 1942, the city administration ordered the construction of a two-and-a-half meter high fence to seal in the remaining Jews, which numbered between 50,000-65,000. The Jews were required to build the fence and cover all the related costs themselves. The work was completed in early September 1942. The area of the Jewish quarter, now formally a ghetto, was diminished considerably and from that time on, the penalty for any Jew caught outside the fence was death. Before the ghetto was sealed completely, in early September 1942, the Judenrat chairman Landsberg, was hanged in public near the Judenrat building, along with other members of the Judenrat and eleven Jewish Order Service men, in an execution commanded by Erich Engels.

The Germans replaced Landsberg with Edvard Eberson and reconstituted the Judenrat to ensure greater compliance with their orders. The change in leadership considerably undermined the Jewish council's standing among the ghetto's population. On 18 November 1942, the Germans conducted another census in the ghetto, and marked about 12,000 Jews with letter codes on the basis of their value to the German war effort. Some 5,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp over a period of three days, under the command of a German police officer Carl Woebke. A few weeks later on 5 December 1942, German police acting under Erich Engels direction torched the ghetto buildings and entire streets to flush out their inhabitants, whom they murdered on the spot or deported, whilst many were sent to Janowska camp, where they were murdered. On 5-7 January 1943, the Germans conducted yet another 'Aktion' in which they murdered approximately 15,000, many were shot in the Piaski Sands, the 'Sands' near the Janowska camp, or in the death camp at Sobibor, near Chelm in the Lublin district of Poland. After this brutal murder action, the ghetto's official status was changed to a 'Julag' – an abbreviation of Judenlager (Jewish Camp), and its administration was handed over to the SS.

On 30 January 1943, the members of the Judenrat were ordered to report with their families, six complied, the others were arrested and nearly all were executed, included the chairman Edvard Eberson. This effectively ended the role of the Judenrat in Lvov, and left the Jewish inhabitants of the Julag with no representation. Under Katzmann's orders all powers with regard to the management of the Julag were transferred to an SS officer Mansfeld. The last vestige of Jewish administration was the Jewish Order Service, which was responsible for maintaining cleanliness, helping to conduct censuses of the Jews, and escorting workers to their places of work. On 13 February 1943, a selection was carried out among the Jewish Order Service and about 200 were allowed to remain in the Julag. The other members along with their families were shot in the Sands. Some 20,000 Jews were marched to work each day, to the accompaniment of a Jewish orchestra that played at Mansfeld's behest. Executions of women were frequent and there were no children present.

On 19 February 1943, Mansfeld was ousted due to charges of corruption and SS- Hauptscharführer Jozef Grzimek took over the running of the Julag. Jozef Grzimek was responsible for combing out the 'illegal Jews' and he imposed strict discipline and sentenced hundreds of Jews to death. Jozef Grzimek was well-known as the liquidator of the Rawa Ruska ghetto, and he subsequently served in the Plaszow Concentration camp in Cracow. In early March 1943 approximately 1,600 adult Jews and their children were murdered after being declared unfit for work and on 17 March 1943 another 1,000 Jews were murdered at the Sands in Janowska in a 'revenge aktion' for the murder of an SS officer by a Jew named Tadek Drutkovski. Two relatively small-scale killing operations took place in the subsequent weeks, are worth recalling: the murder of more than forty children of members of the Jewish Order Service and the liquidation of the hospital in the Julag. Executions of Jews in the Julag and transfers to Janowska labour camp continued during May 1943. The gates to the Julag were at times locked for entire days and Jews were not sent out to work, whilst other groups of workers did not return to the Julag, but were sent to Janowska camp. On 23 May 1943 some 2,000 prisoners in Janowska were murdered in the Sands, to make room for more deportees from the Julag. Armed with the knowledge of the imminent liquidation of the Julag, the inhabitants prepared hideouts and some attempted to escape and the Jewish Underground prepared to resist.

The Germans started to liquidate the Julag on 2 June 1943, but Jewish resistance stiffened and when the Germans and Ukrainians entered the Julag, the resistance fighters killed eight Gestapo men in a two hour battle that ensued. The Germans and Ukrainians retreated and revised their tactics: instead of removing Jews from their homes, they opted to blow up or torch the buildings. The murder operation continued through to 23 June 1943. On the basis of lists the Germans had prepared for approximately 12,000 inhabitants, and were surprised to find nearly 20,000. Many of the Jews were murdered, or perished in the flames or committed suicide, as the ghetto buildings burned to the ground. Approximately 7,000 Jewish workers were sent to the Janowska camp, where they were put through a selection, after which many were murdered. For several weeks after the liquidation of the Julag, the Germans continued to comb Lvov for Jews in hiding. The Janowska camp was liquidated in late November 1943, however, in the spring of 1944, small groups of skilled Jewish workers, who were considered as essential to the German war effort, were concentrated in the former camp. As the Soviets drew near in June 1944, most of these workers were murdered at Janowska, and a small number were sent to other camps, away from the front. The Russians entered Lvov on 27 July 1944, thus, the nightmare of Nazi rule was over.

Sources:

The Yad Vashem Encylopiedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust Volume 1, Yad Vashem, 2009.

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Leon Weliczker Wells, The Janowska Road, Holocaust Library, USHMM, 1999.

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution, Vallentine Mitchell, London 1953

Jozef Grzimek – Personal File - Yad Vashem

Photograph - Chris Webb Private Archive

Document: Wiener Library London

Thanks to Duncan Price for information about the Lvov Gestapo

© Holocaust Historical Society July 24, 2025

Fritz Katzmann along with his subordinate Erich Engels. Thousands of Jews were arrested every day and taken to Janowska camp, where SS officers under the command of Ernst Inquart performed selections and sent the vast majority to Belzec death camp, in cattle cars from the Kleparow railway station. Many Jews tied to escape deportation by hiding in the ghetto, but in most cases the Germans discovered their hideouts. In all some 50,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp, where they were murdered. Following the termination of the second mass deportation to Belzec on the following day, the 24 August 1942, the city administration ordered the construction of a two-and-a-half meter high fence to seal in the remaining Jews, which numbered between 50,000-65,000. The Jews were required to build the fence and cover all the related costs themselves. The work was completed in early September 1942. The area of the Jewish quarter, now formally a ghetto, was diminished considerably and from that time on, the penalty for any Jew caught outside the fence was death. Before the ghetto was sealed completely, in early September 1942, the Judenrat chairman Landsberg, was hanged in public near the Judenrat building, along with other members of the Judenrat and eleven Jewish Order Service men, in an execution commanded by Erich Engels. The Germans replaced Landsberg with Edvard Eberson and reconstituted the Judenrat to ensure greater compliance with their orders. The change in leadership considerably undermined the Jewish council's standing among the ghetto's population. On 18 November 1942, the Germans conducted another census in the ghetto, and marked about 12,000 Jews with letter codes on the basis of their value to the German war effort. Some 5,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp over a period of three days, under the command of a German police officer Carl Woebke. A few weeks later on 5 December 1942, German police acting under Erich Engels direction torched the ghetto buildings and entire streets to flush out their inhabitants, whom they murdered on the spot or deported, whilst many were sent to Janowska camp, where they were murdered. On 5-7 January 1943, the Germans conducted yet another 'Aktion' in which they murdered approximately 15,000, many were shot in the Piaski Sands, the 'Sands' near the Janowska camp, or in the death camp at Sobibor, near Chelm in the Lublin district of Poland. After this brutal murder action, the ghetto's official status was changed to a 'Julag' – an abbreviation of Judenlager (Jewish Camp), and its administration was handed over to the SS. On 30 January 1943, the members of the Judenrat were ordered to report with their families, six complied, the others were arrested and nearly all were executed, included the chairman Edvard Eberson. This effectively ended the role of the Judenrat in Lvov, and left the Jewish inhabitants of the Julag with no representation. Under Katzmann's orders all powers with regard to the management of the Julag were transferred to an SS officer Mansfeld. The last vestige of Jewish administration was the Jewish Order Service, which was responsible for maintaining cleanliness, helping to conduct censuses of the Jews, and escorting workers to their places of work. On 13 February 1943, a selection was carried out among the Jewish Order Service and about 200 were allowed to remain in the Julag. The other members along with their families were shot in the Sands. Some 20,000 Jews were marched to work each day, to the accompaniment of a Jewish orchestra that played at Mansfeld's behest. Executions of women were frequent and there were no children present. On 19 February 1943, Mansfeld was ousted due to charges of corruption and SS- Hauptscharführer Jozef Grzimek took over the running of the Julag. Jozef Grzimek was responsible for combing out the 'illegal Jews' and he imposed strict discipline and sentenced hundreds of Jews to death. Jozef Grzimek was well-known as the liquidator of the Rawa Ruska ghetto, and he subsequently served in the Plaszow Concentration camp in Cracow. In early March 1943 approximately 1,600 adult Jews and their children were murdered after being declared unfit for work and on 17 March 1943 another 1,000 Jews were murdered at the Sands in Janowska in a 'revenge aktion' for the murder of an SS officer by a Jew named Tadek Drutkovski. Two relatively small-scale killing operations took place in the subsequent weeks, are worth recalling: the murder of more than forty children of members of the Jewish Order Service and the liquidation of the hospital in the Julag. Executions of Jews in the Julag and transfers to Janowska labour camp continued during May 1943. The gates to the Julag were at times locked for entire days and Jews were not sent out to work, whilst other groups of workers did not return to the Julag, but were sent to Janowska camp. On 23 May 1943 some 2,000 prisoners in Janowska were murdered in the Sands, to make room for more deportees from the Julag. Armed with the knowledge of the imminent liquidation of the Julag, the inhabitants prepared hideouts and some attempted to escape and the Jewish Underground prepared to resist. The Germans started to liquidate the Julag on 2 June 1943, but Jewish resistance stiffened and when the Germans and Ukrainians entered the Julag, the resistance fighters killed eight Gestapo men in a two hour battle that ensued. The Germans and Ukrainians retreated and revised their tactics: instead of removing Jews from their homes, they opted to blow up or torch the buildings. The murder operation continued through to 23 June 1943. On the basis of lists the Germans had prepared for approximately 12,000 inhabitants, and were surprised to find nearly 20,000. Many of the Jews were murdered, or perished in the flames or committed suicide, as the ghetto buildings burned to the ground. Approximately 7,000 Jewish workers were sent to the Janowska camp, where they were put through a selection, after which many were murdered. For several weeks after the liquidation of the Julag, the Germans continued to comb Lvov for Jews in hiding. The Janowska camp was liquidated in late November 1943, however, in the spring of 1944, small groups of skilled Jewish workers, who were considered as essential to the German war effort, were concentrated in the former camp. As the Soviets drew near in June 1944, most of these workers were murdered at Janowska, and a small number were sent to other camps, away from the front. The Russians entered Lvov on 27 July 1944, thus, the nightmare of Nazi rule was over.

Sources:

The Yad Vashem Encylopiedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust Volume 1, Yad Vashem, 2009.Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Leon Weliczker Wells, The Janowska Road, Holocaust Library, USHMM, 1999.

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution, Vallentine Mitchell, London 1953

Jozef Grzimek – Personal File - Yad Vashem

Photograph - Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2014