Kozienice

Kozienice Bahnhof (Chris Webb Private Archive)

The town of Kozienice lies approximately 50 miles southeast of Warsaw on the River Zagozdzonka. In 1939, the town had slightly less than 9,000 inhabitants, of whom roughly half were Jewish.

German forces occupied the town on September 9, 1939, and they appointed Marian Trug as Mayor, and an ethnic German, from Wolka Tyrzynska, named Miller as his deputy. The main German police presence in the town was a squad of Gendarmerie, under the command of Leutnant Henning. From September 1939, until June 1941, there was a strong Wehrmacht garrison in Kozienice. The Selbstchutz subsequently renamed the Sonderdienst and the Baudienst (Construction Service) were recruited mainly from local ethnic Germans, the so-called Volksdeutsche.

In October 1939, the Germans appointed a Jewish Council (Judenrat) consisting of 12 members, with A.H. Perle as its chairman. The Judenrat had to implement all German orders concerning the Jewish community. Other members of the Judenrat included Shmuel Weinberg, Abraham Shabason, Pinkas Freilich, Zygmunt Halputer, and Josef Lichtenstein.

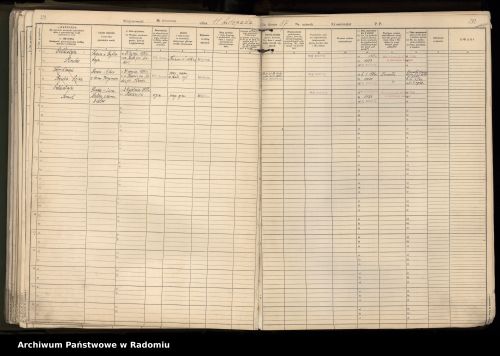

On German orders, a complete list of Jewish residents in Kozienice was prepared. It lists 4,248 individuals, including their first and last names, addresses, age and occupation. An example of the census prepared by the Judenrat, shows Pinches and Szmul Goldsztejn, who were both deported to the Treblinka death camp on September 27, 1942:

Goldsztejn Family - Pinches and Szmuel Entries (Radom Muzeum)

The surviving reports of the Judenrat to the Security Police in Radom contained detailed information on the changes in the Jewish population throughout the occupation until the summer of 1942. While the number of births remained unchanged from 1939, to 1941, the number of deaths climbed steadily, from 42 in 1939, to 210 in 1941, then 255 in the seven months to the end of July 1942.

A number of Jewish charitable institutions operated during the occupation, including the Committee for Aid to the Poor, the Jewish Social Self-Help (JSS),and the 'Drop of Milk' Society, to feed poor infants. At the end of October 1941, a hospital was opened under the management of Dr. Joel Wajnber to deal with serious epidemics. In 1942, the Society for Improvement of Sanitation was established. When a severe epidemic of typhus broke out in the spring of 1942, the Department of Sanitation took measures to prevent its spread, including extensive programs of delousing and vaccination.

The Judenrat mediated all contacts between the Jewish community and the outside world, serving as a Post Office, a Tax Office, and also a commercial bank. It had to collect money from the Jews to pay the levy demanded by the Germans for the benefit of 'needy Germans,' - Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, (NSV). The levy was 18,500 zloty in 1939, and further demands followed.

In principle the Jews were not allowed to work independently. Only a few of them managed to find some gainful private employment or to continue their previous commercial activities. Many Jews and some Poles were recruited for forced labour, digging canals in the area between Kozienice and Gniewoszow. From the first day of the occupation, the Judenrat had to provide a quota of about 500 labourers per day. These people worked on road construction and maintenance, in forestry and agriculture, and on the railway. Other assignments included digging peat, working in the gunpowder factory in Pionki, and performing various cleaning duties at various Wehrmacht and Gendarmerie posts, as well as in the Town Hall.

Other groups were detailed to sweep the streets and clear snow in the winter. Some Jews were also employed by private enterprises such as the construction firms of Heinrich Koehler, Paul Gatz of Jedlnia and the Kozienice- based companies of Czarnota- Bojarski and Eng. Gorczycki (on drainage works). The workers were paid very low wages. In order to survive, Jews had to stretch out their last reserves of food and money and sell off any remaining property. They also obtained some aid from the Jewish Social Self-Help (JSS),and continued to make and trade items, illegally. Smuggling and begging was widespread.

There was very little in the way of cultural life, but Jews continued to pray in the synagogue. Religious observance and Jewish responses to adversity in Kozienice were undoubtedly influenced by the community's strong Hasidic character. A small school continued operating for approximately 70 pupils, taught by Rochama Frajlich.

Until December 1941, Jews were relatively free to move about within the town and even to visit the surrounding villages. At the end of December, in response to orders issued by the German civil authorities for Distrikt Radom, the Judenrat began to establish a Jewish residential living quarter in Kozienice. All Jews living outside the designated quarter had to move into it, and any Poles living there had to move out. The streets within the Jewish quarter were 11 Listopada, Pilsudski, 3 Maja, Lublin, Krotka, Magietowa, Pieracki, Targowa, Drzewna, Browarna, Pusta, Czwartek, Szpitalna, Mlynska, Nowy Swiat, Polskiej Organizacji Wojskowej, and Harmenicka. The ghetto remained open for several months and was guarded only by Jewish Police internally and the Gendarmerie externally. It was enclosed with a barbed-wire fence during May 1942. Anyone caught leaving the ghetto faced the death penalty.

After July 1942, Jews from the surrounding towns and villages were systematically relocated into the Kozienice ghetto. By August 1942, a few weeks before its liquidation, approximately 13,000 Jews had been concentrated in the Kozienice ghetto, which became immensely overcrowded.

The German police conducted the liquidation of the Kozienice ghetto on September 27, 1942. First SS forces, Gendarmerie, and Ukrainian auxiliaries surrounded the ghetto early in the morning. The Jews were forced to leave their houses and gather on Targowa and Koscielna Streets. The people were only allowed to take 15 kilograms of luggage with them. The older people were loaded onto trucks, the sick and anyone attempting to resist, as well as Jews in the hospital, were shot on the spot. In total at least 100 people were shot in Kozienice on this day.

Columns of Jews escorted by the Germans and Ukrainians marched to the railway station at around 9:00 a.m. watched by the local inhabitants. On reaching the station, they were searched thoroughly and deprived of any valuables. The first train to the Treblinka Death Camp departed in the afternoon, and the next, a short time later, there were 60 cattle cars, altogether with approximately 150 people in each car, ready to depart.Railway documentation which has survived confirm the exact date these special trains from Kozienice arrived at Treblinka.

Paul Goldstein wrote down an the record of his father's speech that he delivered at the graveside for the Kozienice Memorial Service.

'On September 27, 1942, the Nazis ordered all the Jews in my father's hometown of Kozienice to assemble at 5:00 a.m. in the town square on Targowa Street. My father, his parents and his sisters family didn't leave as ordered. Soldiers burst into their house and shot his mother as she lay ill in bed. They dragged his father by the beard and paraded him through the streets. My father, his father, his sister and her husband and two children were packed into cattle cars and sent to Treblinka.'

Paul Goldstein has written an as yet unpublished account based on his father's recollections entitled 'A Shoemakers Tale from Kozienice' : from which this is taken:

'On Shimini Atzeret, the day before Simchat Torah in 1942, the Jewish population of about 13,000 from Kozienice and surrounding towns was deported in cattle cars to Treblinka.The old and sick were shot before they reached the train station. Dr Abramowitz, the only Jewish doctor in town, his wife and two daughters took poison pills and died before the deportation. The cars were packed, the doors were locked, and we were without water or air.... each of us pressed against each other.'

Szmul was selected to live and escaped from Treblinka during the prisoner revolt on August 2, 1943. His other family members were all gassed on arrival at Treblinka.

The Germans retained in Kozienice a group of several dozen male Jews, in order to clear out the remaining property from the ghetto area. This task lasted until December 1942. Less valuable belongings and everyday household equipment such as bed-clothers, underwear, clothing, shoes, furniture and kitchen utensils were sold to the local Poles at auction, or they were plundered. The more valuable items were locked up and guarded in the Gestapo offices.In the spring of 1943, most of the former Jewish houses were demolished. In the summer Jewish tombstones were taken to pave the square in front of the Gendarmerie headquarters - the former vicarage, and other places, and the Jewish cemetery was eventually leveled.

The largest group of survivors was composed of those who made it through the harsh conditions in the death camps, and other camps until liberation. A smaller number managed to survive in hiding, usually with the help of several Polish helpers. Moshe Grynberg and his wife, for example, were rescued by the Gawelek family from the neighbouring village of Sieciechow, who were honoured with the title of the 'Righteous Among the Nations, by Yad Vashem.

There were at least two trials in post-war Poland, concerning crimes committed against the Jews of Kozienice. In one Bronislaw Salomon was accused of robbing Jewish property, and he was sentenced to death. In another Stanislaw Sotr was convicted of denouncing four Jews to the Gendarmerie, for which he received from the Germans some sugar and a coat as a reward. He was also sentenced to death, but managed to escape execution by escaping from Radom prison, where he was being held.

Sources

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012.

Paul Goldstein - A Shoemakers Tale from Kozienice - unpublished memoir of Sam Goldstein's account

Thanks to Paul Goldstein, for his support and permission to quote from his father's memoir

Photograph: Chris Webb Private Archive

Image from the Radom Muzeum, Poland

Thanks to Ewa Telezynska Warsaw, for the Kozienice ghetto census

© Holocaust Historical Society 17 January 2022