Minsk

Minsk - Column of Jews (Bundesarchiv)

Minsk is the capital and largest city of Belarus, situated on the Rivers Svislach and Nyamiha. In 1926, the Jewish population of Minsk stood at 53,686, by June 1941, that number had grown to 80,000, and this constituted one-third of the Jewish population. Only a small fraction of the Jews managed to escape from the city in the six days between the German invasion of the Soviet Union and the occupation of Minsk on June 28, 1941. German parachutists who had been dropped east of the city intercepted thousands of Jews who were trying to flee and forced them to return to Minsk. When the civil administration was established, Minsk was chosen as the seat for the headquarters of the Generalkommissar fur Weissruthenien, under the control of Wilhelm Kube.

Wilhem Kube -second from Left - in a Polish Cemetery in Minsk (Bundesarchiv)

On July 8, 1941, the Germans killed 100 Jews and thereafter the murder of Jews by the Germans either singly or in groups, became a daily occurrence. On July 20, 1941, the Nazi authorities ordered the establishment of a ghetto. The area of the ghetto comprised thirty-four streets and alleys, as well as the Jewish cemetery.

Some of the streets included in the ghetto were:

Kollektornia, Kolkhoznaia, Nemiga, Obuvnavia, Perekopskaia, Respublikanskaia, Shornaia, Zaslavskaia

Some of the lanes included in the ghetto were:

Kolkhoznyi, Mebel'nyi, Vtoroi Opanski, Yubileny Square

The ghetto was surrounded by thick rows of barbed-wire, watchtowers were erected and round-the-clock surveillance was established. A living space of 1.5 square meters was allotted for each person, with no space allotted for children. Thousands of the ghetto inhabitants lived among the ruins of destroyed or gutted houses without floors or windows. A curfew was in force from 22.00 hours to 05.00 hours. Jews from Slutsk, Dzerzhinsk, Cherven, Uzda and other nearby locations were resettled in the ghetto. Married couples with one non-Jewish partner were also put into the ghetto, along with their children. Altogether, approximately 100,000 people were rounded up and incarcerated in the Minsk ghetto.

During August 1941, 5,000 Jews were seized and murdered, and the surviving Jews were forced to pay a ransom, to report every Sunday for roll-call, and to wear a yellow badge on their backs and chests, as well as a white patch on their chests with their house number. News of the killings in Minsk was sent to Heinrich Muller, head of the Gestapo ,who ordered Adolf Eichmann, the Jewish expert in the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) to report to Minsk, and observe what was taking place there. Twenty-years later, in a court in Jerusalem, on trial for his life, Adolf Eichmann described the official visit: Eichmann travelled first to Bialystok and then onto Minsk, and on reaching the execution site in Minsk he found that:

'There were the piles of dead people. They were shooting into the pit - it was a rather large one, so I was told, perhaps four to five times the size of this room, perhaps even six or seven times. I didn't think much about it, because I could hardly express any thoughts about it- I only saw it and that was quite enough - they were shooting into the pit and I saw a woman, her arms seemed to be at the back, and then my knees went weak and I went away.'

During July 1941, a Jewish Council (Judenrat) was established with Eliyahu Myshkin at its head. He was the former vice-director of the Ministry of Commercial Trade. The Judenrat was located at Yubileiny Square, and it had seven departments, Health, Housing, Labour, Registration, Supplies, Welfare and Workshops. The first duty of the Minsk Judenrat was to register the entire Jewish population, and this was completed by July 15, 1941. All the men in the ghetto were registered for labour duties and a labour camp was established on Shirokaya Street where Soviet Prisoners of War accused of offences, as well as Jews, were sent. The camp also came to be used as a transit camp for those destined for liquidation. Amongst a number of outrages on July 21, a group of 45 Jews were roped together and ordered to be buried alive by 30 Russian prisoners. The Russians refused to carry out this work and all 75 captives were shot.

Minsk Judenrat (Bundesarchiv)

On August 15, 1941, Reichsfuhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler visited Minsk and witnessed the shooting of 100 Jews by an Einsatzkommando led by Artur Nebe. According to Karl Wolff, who was then Himmler’s Liaison Officer at Hitler’s headquarters, he recalled that Himmler was badly shaken by the gruesome experience and instructed Nebe to find a better method for the mass murder.

On November 7, 1941, the Germans conducted an 'Aktion' in several of the ghetto's streets, rounding up 12,000 Jews and murdering them in nearby Tuchinka. The houses vacated by the murdered Jews were now filled with Jews from Germany - the so-called Hamburg Jews - because that was where the first group came from, transported to Minsk, in the wake of the November 7, 'Aktion.'

The transports to Minsk from Hamburg, were guarded by members of Reserve Police Battalion 101 and one of the escorts recalled:

'In Hamburg the Jews were told at the time that they would be allocated a whole new settlement territory in the east. The Jews were loaded into normal passenger cars .... accompanied by two cars of tools, shovels, axes etc. as well as large kitchen equipment. For the escort commando a second class carriage was attached. There were no guards in the cars of the Jews themselves.

The train had to be guarded on both sides only at stops. After about four days' journey we reached Minsk in the late afternoon. We learned of this destination for the first time only during the journey, after we had already passed Warsaw. In Minsk an SS commando was waiting for our transport. Again without guard, the Jews were then loaded onto the waiting trucks. Only their baggage, which they had allowed to bring from Hamburg, had to be left behind in the train. They were told it would follow.

Then our commando was finally driven to a Russian barracks, in which an active German police battalion was lodged. There was a Jewish camp nearby. From conversations with members of the above-mentioned police battalion we learned that some weeks ago this unit had already shot Jews in Minsk. We concluded from this fact that our Hamburg Jews were to be shot there also.'

The deportees from Hamburg were followed within days by more than six thousand deportees from Bremen, Frankfurt-am -Main and the Rhineland. On November 18, 1941, a transport arrived from Berlin. A twenty-two year old Jew Haim Berendt was among the deportees and on reaching Minsk, he recalled:

'The carriages were opened and they started beating us up, driving us out of the carriages in a hurry and, within a moment, there were complete chaos. He who succeeded in getting out of the door was beaten up, women, children and men.'

The Berlin deportees were taken beyond the Jewish ghetto of Minsk to a special ghetto for the German Jews known as 'Ghetto Hamburg' and once there they became part of the Jewish labour force in Minsk.

A second 'Aktion' took place on November 20, 1941, in which the Germans murdered another 7,000 Jews, also in Tuchinka. After the two 'Aktionen' the ghetto underground intensified its activities, making preparations for escapes to the forests and extending its network of hiding places in the city. On the night of December 21, 1941, the bodies of several thousand Soviet Prisoners of War were laid out by the Germans along a six kilometre stretch of road in Minsk. On the previous day most of the Russians had been deliberately frozen to death in a march across open fields. Some had been shot when in desperation they had sought some shelter from the fierce wind.

Eliyahu Myshkin co-operated with local resistance and in February 1942, he was arrested and hanged. His successor Moshe Yaffe, retained the Judenrat's support of the resistance groups, but two Jewish collaborators, Epstein and Rosenblatt managed to infiltrate the Judenrat and to work for the Germans within it. The heads of several of the Judenrat's departments in Minsk - Rudicer of the economic section, Dulski of the housing section, Goldin of the workshop section, and Serebianski, the police commander - all co-operated with resistance groups, providing them with clothing, shoes, hiding places, and false documents. Serebianski went so far as to hire members of the resistance into the ghetto police force. Also active in helping the resistance in Minsk were two of the secretaries in the labour department, Mira Strogin and Sara Levin.

The first week of March 1942, saw the Jewish festival of Purim, a time of rejoicing at the defeat of Haman the Amalekit. It was Haman who had tried, in ancient days to destroy all the Jews of the Persian Empire. In Minsk, on the eve of Purim, 1942, the Germans ordered the Judenrat to handover 5,000 Jews for deportation 'to the west.' The Judenrat did not know what to do. Some members of the Council suggested that small children, and the elderly, might be sent away. But those Jews who wanted no collaboration whatsoever with the Germans in these demands insisted on 'no trading in Jewish souls.' Hiding places had already been prepared in cellars and ruined buildings. Those who felt to be in danger hid.

On the morning of March 2, 1942, the Jewish labour battalions were sent out of the ghetto as usual. Then the Gestapo approached the Judenrat for the 5,000, urging haste, 'because the trains were ready and waiting.' The Judenrat refused. In fury, the Gestapo sent German and White Russian policemen to search the ghetto. Reaching a children's nursery, they ordered the woman in charge, Dr. Chernis, and the supervisor, Fleysher, to take the children in their care to the Judenrat building.

This in fact was a murderous trap. On reaching a specially dug pit on Ratomsakaya Street, the children were seized by the Germans and White Russians, and thrown alive into the deep sand. At that moment, several SS officers, among them Wilhelm Kube, arrived , whereupon Kube, immaculate in his uniform, threw handfuls of sweets to the shrieking children. All the children perished in the sand.

That night, when the Jewish forced labourers returned to Minsk, from their work outside the ghetto, they were ordered to lie down in the snow outside the ghetto gates. Anyone who tried to get up and run into the ghetto were shot. Others were taken to the pit in Ratomsakaya Street and murdered. Some were marched away from the city, to the Koidanovo forest and murdered there. At least 5,000 Jews were killed in Minsk during that Purim day.

On May 7-8, 1942, the Germans established a camp at Maly Trostinec, east of Minsk, three miles from the village of Maly Trostinets in the Blagovshchina Forest, solely for the purpose of extermination. It was under the command of SS- Scharführer Heinrich Eiche, and the camp served as a killing centre for local Jews, as well as Jews resettled from Austria, Germany and Bohemia and Moravia.

On June 2, 1942, there was a deportation of Jews from Vienna. They were taken by train to Minsk, and there in the Minsk ghetto, shared the fate of tens of thousands of deportees to Minsk: starvation, sadistic cruelties and mass executions. Among those deported on June 2, was a milliner by profession, Elsa Speigel. It was three weeks before her thirty-third birthday. She was never heard of again. But back in Vienna, she left her tiny son, Jona Jakob Speigel, a baby of five and a half months. Elsa Speigel's decision to leave her baby in Vienna saved his life. Three and a half months later, Jona was deported from Vienna to Theresienstadt, the fortress ghetto in Bohemia and Moravia. By a miracle he was still in Theresienstadt on the last day of the war, when the camp was liberated by the Red Army.

Between July 28 and July 31, 1942, the Germans killed some 30,000 Jews, among them the German Jews, who were in a separate ghetto in Minsk. The Germans forced the head of the Judenrat Moshe Yaffe to speak to the Jews in terms designed to allay their fears, but when trucks and gas vans burst upon the square where they had assembled, Yaffe cried out, 'Jews, the bloody murderers have deceived you -flee for your lives!' Yaffe and the ghetto police chief were among the victims of that 'Aktion,' following which, only 9,000 Jews were left in Minsk. The Judenrat ceased to exist, and Jewish collaborators

On August 4, 1942, a train with 1,000 Jews left Theresienstadt and six days later the transport reached Maly Trostinets, where it stopped in open country. Forty 'experts' were taken from the train in Minsk. The remaining 960 deportees were ordered out of the carriages and loaded into vans for the next stage of their journey, and the vans drove off towards the forest. The vans, were in fact gas vans, and once they reached the forest, the doors were unlocked and the bodies of the gassed Jews were thrown into mass graves. Of a thousand Jews sent from Theresienstadt to Maly Trostinec, in a further transport on August 25, 1942, only twenty-two of the younger men were taken to work at an SS farm. The remainder were murdered in the gas vans. Of the twenty-two men sent to the SS farm, only two survived the hard labour and sadism of their overseers and escaped in May 1943, to join the partisans. One was killed in action, the other survived the war. By August 1, 1942, there were officially 8,794 people still alive in the ghetto. The SS, Police and Gestapo officials who were responsible for numerous atrocities were Fichtel, Hettenbach, Menschel, Richter, Wentske, and others.

Early in February 1943, two previously unknown Germans appeared in the ghetto, Adolf Ruebe and his assistant Michelson. Over the ensuing months Rube and Michelson, the new Police Chief Bunge and his deputy Scherner, terrorised the ghetto. Shootings became so commonplace that people were afraid to venture onto the streets. Orphaned children, the elderly and the disabled were systematically exterminated.

Niuta Jurezkaya, a well-known local doctor escaped from the ghetto in Minsk and fled to the forests, but she was captured and brought back to Minsk, where she was tortured. She was asked, 'Who was with you?' She replied, 'All of my people were with me.' She was shot on June 16, 1943. Between four days from September 18 to September 22, 1943, transports of Minsk Jews, including Soviet Jewish former Red Army soldiers were deported to the Sobibor death camp in the Lublin district, and also on September 10, 1943, some 2,000 Jews were also sent to the Budzyn Labour Camp near Lublin.

Among the prisoners was Alexsander Pechersky, better known as Sascha, who had been imprisoned in the Sheroka Street Labour Camp in Minsk from September 1942 and was taken to Sobibor, along with other former Red Army soldiers such as Arkadij Wajspapir, Boris Taborinskij. Sascha planned and led the prisoner revolt in the Sobibor death camp on October 14, 1943. This has gone down in history as one of the most courageous acts of heroism by Jews during the Second World War.

On October 21, 1943, one week after the Sobibor death camp revolt, all 2,000 Jews in Maly Trostinec, the last survivors from the Minsk ghetto were rounded up and killed in pits outside the city. On the day of this massacre, twenty-six Jews hid in an underground bunker, which had been built by two Jewish stonemasons. In the first month three died, the others buried them in the ground, on which they themselves lay. Two girls left the hide-out in search of food, but they were captured and killed. After eight months, only thirteen of the twenty-six remained alive. There was no more food - the children were in a coma, and the adults were weak from hunger. It was then that a girl called Musya left the hide-out in search of food, she did not look like a Jewess, but she took the risk, nevertheless, of running into someone she knew, and who might denounce her to the Germans.

During her search for food and help, Musya met Anna Dvach, a White Russian woman, with whom she had worked in the same factory before the German invasion. Anna took her home and gave her food and shelter, and then sent her back with food for the other Jews in hiding. From that day until the arrival of the Red Army, some six months later, Anna Dvach ensured the survival of the thirteen Jews. When Minsk was liberated on July 3, 1944, only a few Jews who had gone into hiding during the final 'aktion' remained alive.

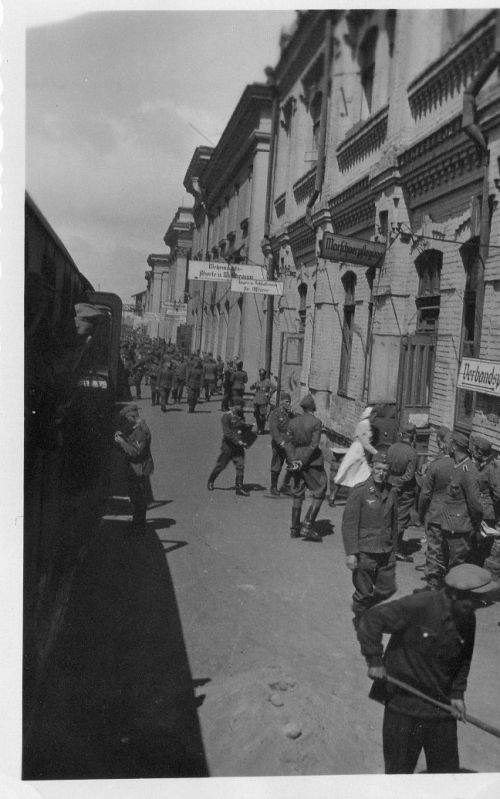

Minsk - Main Station (Chris Webb Archives)

Minsk - The Use of Gas Vans

In Minsk, the Germans used gas vans to murder the Jews, and a number of testimonies have survived:

In the middle of December 1941, three gas vans were brought from Berlin to Riga, and put at the disposal of the BdS of the Eastern Territories. There were two small 'Diamond ' vans and one large 'Sauer' van. Two drivers Karl Gebl and Erich Gnewuch, arrived from Berlin before Christmas 1941. At the beginning of 1942, they were dispatched with two gas vans to the commander of the BdS regional office for Byelorussia located in Minsk and known, like the other regional offices, by the initials KdS. Gnewuch said in his deposition, 'On orders from my department, I too drove a gas van from Berlin to Minsk. These vans had been constructed with a lockable cargo compartment, like a removals van. It could hold about fifty to sixty Jews. I personally gassed Jews in this gas can.'

On July 31, 1942, a convoy of about one thousand Jews arrived at the Minsk station from Theresienstadt. Because an 'aktion' was being carried out in the Minsk ghetto, the convoy was diverted to Baranovichi, where two gas vans were waiting. A member of the local SD office, named Dittrich, later testified that the Jews had been exterminated by the Baranovichi commando. Two gas vans had been used, one driven by Gebl, who according to Dittrich came from Minsk, or from Berlin, and another driver whose name he did not remember (it was Johann Hassler). He said that both vehicles made seven to nine trips that day. Dittrich estimated the number of victims gassed at between five hundred and seven hundred. Both vans were crammed full, so that when the doors were opened the bodies fell out.

During his interrogation, Hassler admitted having participated in the gassing operations at Baranovichi. One of the survivors of the town's ghetto, Dr. Zalman Levinbuck, mentioned this operation in his testimony. He spoke of a convoy of Czech Jews who were taken from the station by truck: 'Among the trucks were huge vans with doors that could be sealed hermetically.... We called these airtight vans 'dushegubky' which means 'soul killer' in Russian. They transported people who were already dead and didn't need to be shot. They were poisoned on the way with gas and exhaust fumes, which resulted from the combustion of gasoline in the engine. These exhaust fumes were introduced into the van through a special hose, instead of being released into the air as is normal, and so people were killed by the carbon monoxide.

Dr. August Becker who was a Tiergartenstrasse 4 expert who worked for the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) described a trip to the Eastern Territories in connection with the use of gas vans to exterminate Jews:

'In Riga I learned from Standartenführer Potzeit, Deputy Commander of the Security Police and SD in Riga, that the Einsatzkommando operating in Minsk needed some additional gas vans as it could not manage with the three existing vans that it had. At the same time I also learned from Potzeit that there was a Jewish extermination camp in Minsk. I flew to Minsk by helicopter, correction in a Fiesler Storch, belonging to the Einsatzgruppe. Travelling with me was Hauptsturmführer Ruhl, the head of the extermination camp at Minsk with whom I had discussed business in Riga. During the journey Ruhl proposed to me that I provide additional vans since they could not keep up with the exterminations. As I was not responsible for the ordering of gas vans, I suggested Ruhl approach Rauff's office. When I saw what was going on in Minsk - that people of both sexes were being exterminated in their masses, that was it - I could not take anymore and three days later, it must have been September 1942, I travelled back by lorry via Warsaw to Berlin.'

At the end of October 1943, the Byelorussian gas vans were concentrated in Minsk for the liquidation of the ghetto there. The 'aktion' lasted ten days. Thousands of Jews were killed. The driver Gnewuch, confirmed that a 'ghetto operation' took place in the autumn of 1943. I was put into action only once with the gas van. I made three trips with it to the execution site. I gassed about 150 to 180 people. Adolf Rube and someone called Goebel also drove gas vans. We had been assigned to this operation with three vehicles. Whenever I was gassing Jews, Goebel and Rube were gassing Jews too. The platoon from the Second Police Battalion of the SD was detailed to this killing operation. Its leader, a Russian named Ramasan Sabitovitch Tchugunov, stated during his interrogation: ' We shoved them into the gas vans. These vans were packed full of people from the ghetto, the doors were hermetically sealed, and they left the ghetto. We transported men, women, old people, and children. They were not allowed to bring anything at all with them. There were about 50 people in each van. About a thousand people were transported that day. Boris Dobin, a Jew from the Minsk ghetto, also testified to the use of gas vans in the city. He saw these vans in action on several occasions: 'The brutal guards took away van loads of peaceable Soviet citizens who had been interned in the camps. They were loaded into trucks and also onto vehicles equipped to kill by means of exhaust fumes. These vehicles had all metal cargo compartments. The prisoners called these vehicles gas vans.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, published by Collins London 1986

Chris Webb, The Sobibor Death Camp, History, Biographies, Remembrance, ibidem-verlag, Stuttgart 2017

Christopher R. Browning, Ordinary Men - Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, HarperPerennial 1998

Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

W. Dressen, E.Klee, V.Reiss, Those Were the Days, published by Hamish Hamilton, London 1991

Photographs: Bundesarchiv, Chris Webb Archives

www. Holocaustresearchproject.org - online resource

www. Nizkor: The Einsatzgruppen and Gas Vans in the Eastern Territories

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018