Kosow Lacki

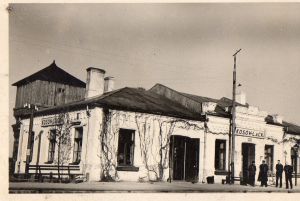

Kosow Lacki - Railway Station

Kosow Lacki is located 55 miles north-east of Warsaw. On the eve of the Second World War, the town had approximately 1,400 Jewish residents, which made up 85% of the total population. In the opening weeks of the Second World War, Kosow Lacki’s location, 6 miles west of the Bug River, enabled a number of the town’s Jews to escape from German occupation. Although the Germans entered the town on 11 September 1939, without any resistance from the Polish army, they did not stay long. As Kosow Lacki was originally assigned to the Soviet occupation zone, within the terms of the Molotov- Ribbentrop pact, the Red Army occupation proved equally brief. They occupied the town on 17 September 1939, but left after only a few days, retreating behind the Bug River, and some of the towns younger Jews left with the Red Army. With the Germans re-taking control of the town at the end of September 1939, there was a sharp increase in the Jewish population, which more than doubled and by December 1941, there were 3,800 Jews living in the town. Part of the reason for this increase resulted from Jews who were denied entrance at the Soviet border, and who found it impossible to survive in the nearby forests over the winter. The increase was also caused from German forced resettlement of Jews in the Warsaw district, from such locations as Wyszkow nad Bugiem, Pultusk and Ostrow Mazowiecka.

On 13 December 1939, the German authorities charged the town’s rabbi, Jerrucham Fishl Don, with receiving and caring for 750 Jewish deportees who had arrived from Kalisz, which had been incorporated into the Reich. Even though the Germans had taken some of the Jews from Kalisz to Sterdyn in March 1940, the sudden influx created enormous pressure on Jewish families in Kosow Lacki. Approximately 15 families from Kalisz, some 70 people, were given shelter in the town’s synagogue. Don expected every Jew to take in as many families as they had rooms for. To resolve tensions over the resulting cramped housing situation, the rabbi established a committee composed of Jewish representatives from Kosow Lacki and Kalisz. The committee ordered the Jews of Kosow Lacki to feed their guests from Kalisz on Fridays and Saturdays. Don also established a kitchen and dining hall, which served hot meals free of charge to the refugees and local Jews displaced by the deportees. In the autumn of 1939, the Germans ordered the creation of a Jewish Council (Judenrat) to act in the name of the town’s Jewish population. In Kosow Lacki, the Judenrat, composed of the pre-war Kehillah functionaries, was initially chaired by Itzchak Liberman. Youth leaders from different political parties also organised, with permission from the official Judenrat, a parallel Judenrat. This ‘youth Judenrat’ appears to have provided many of the ghettos social services. It organised a sanitation committee, opened a small hospital for contagious diseases, and distributed food to the weak, sick and impoverished. It also created a social committee and arranged special passes enabling some, including the Jewish Police to remain outside beyond the curfew. The date the Jewish Police was formed is not known, but the 20 –man force was headed by an officer named Enoch. Although the town’s Jews were expected to meet German demands for money, furs, and exotic foodstuffs, the German insistence on forced labour posed the greatest challenge to the Judenrat. While organising female work brigades for nearby farms, which had been expropriated for German and Ukrainian use proved relatively easy, the Judenrat experienced difficulties finding 500 to 600 men willing to travel 90 miles by train to spend a week draining swamps in Leki. The main Judenrat turned to the ‘youth Judenrat’ to fulfil the quota for workers in Leki. They did so by establishing a Work Committee to assign forced labour duties. The ‘youth Judenrat’ also organised a militia of Jewish youth to enforce the labour quotas. The main Judenrat also broke up a Sabbath strike of female farm labourers, launched within the first weeks of their assignment.

The Judenrat assisted the German police in arresting the protestors’ mothers, which soon brought the strikers back to work to obtain their release. In his monthly report for February 1941, the Sokolow Kreishauptmann noted that the movement of Jews in the Kreis had been forbidden and that the establishment of six Jewish residential districts, including one in Kosow Lacki, would be completed in March 1941. Any Jews remaining in the villages were being moved to one of these six places. The same report indicated that the ghettos would be enclosed as soon as the weather permitted. However, most eyewitness testimony maintains that Kosow Lacki remained an ‘open ghetto,’ at least up until the main deportation ‘aktion’ in September 1942. It seems that as the majority of the town’s population was Jewish, the Germans designated Kosow Lacki a ‘Judenstadt’ (Jewish Town) – and rather than establish a separate ghetto within the town, they treated the entire town as a ghetto, refusing to allow Jews to cross the town’s borders. In early 1941, the welfare expenditure of the Judenrat expanded considerably, from a monthly average in 1940 of about 800 zloty to around 6,500 zloty per month. This steep increase resulted primarily from the new orders preventing Jews from leaving the town, as previously trade and labour in the surrounding villages had been a major source of food and income for many Jews. The Judenrat responded by launching a ‘Bread Action’ in which all ghetto residents received half a kilogram of bread free of charge, subsidised with the help of the Krakow-based American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) in January and February 1941. As Germany began preparing for the invasion of the Soviet Union in the spring of 1941, the Jews from Kosow Lacki were assigned the task of unloading German trains at the railroad station. Then on 22 June 1941, following the German invasion, Soviet airplanes bombarded Kosow Lacki, sparking a fire in which 42 people died. Jewish labour obligations were now increased, as a number of craftsmen formed the worker pool at the Treblinka labour camp, less than 8 miles away. In the autumn of 1941, SS troops and Ukrainian guards surrounded Kosow Lacki and took local craftsmen, their assistants and their equipment to the Treblinka labour camp on trucks. A second round-up of craftsmen took place in 1942. Because carpenter Yankel Kuklavka was not at home at this time, the Germans threatened to kill many of the town’s Jews if he were not surrendered. Kuklavka subsequently managed the carpentry workshop at the Treblinka labour camp. The labour camp round-ups were accompanied by SS demands for ‘material contributions.’ Several weeks after a round-up, SS men presented the Judenrat with lists of demands for a range of goods, from tools and building materials for the labour camp to luxury items and cash payments for the camp’s German staff. To obtain the construction materials, the Jewish community took down buildings partially destroyed by the Soviet bombing. The Judenrat imposed stiff taxes to meet the SS demands and resorted to harsh measures to extract exotic foodstuffs from local residents, for example, locking up the head of the Cegal household for his refusal to hand over coffee sent from France. Some residents of Kosow Lacki’s ghetto believed that the craftsmen labour and the town’s financial contributions had established a special relationship with the SS at the Treblinka labour camp.

When in 1942, SS officers from the Treblinka death camp gave a similar list of demands to the Judenrat, it appealed directly to Theodor van Eupen, the commander of the Treblinka labour camp, with some success. However, the increasing failure of bribes and ransoms to protect the Jews undermined the Judenrat’s authority and provoked a leadership crisis. In early 1942, the SS murdered several craftsmen at the Treblinka labour camp, including locksmith Mordechai Liberman, son of the Judenrat chairman. After losing his son, Itzchak Liberman, the Judenrat chairman began drinking heavily. He was found shot dead on the street. His successor Alter Burstein, failed to secure the release from the Pawiak Prison in Warsaw, three young Jewish leaders. The Judenrat’s policy of levying heavy taxes to pay for ransoms came into question, particularly after the parents of Joshua Liberman received a letter telling them their son had died in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Jews in Kosow Lacki were relatively well informed about the terrible events unfolding around them. They had learned about the creation of the Warsaw ghetto from Jews who escaped from the city in August 1941, seeking better conditions in Kosow Lacki’s open ghetto. Polish traders who came to the town to hire Jewish middlemen to help them with illicit trading brought news of deportations from the Warsaw ghetto. The craftsmen who worked at the Treblinka labour camp, who were able to return to their homes at weekends in the spring of 1942, reported on the construction work at the Treblinka death camp. Some of the ghetto residents in Kosow Lacki also gave assistance to at least three Jews who had jumped from transports headed to the death camp. The town offered similar protection and travel papers to four escapees from the death camp itself. Some younger Jews in Kosow Lacki began preparing hiding places in early autumn 1942. The funeral for Joshua Liberman’s grandfather, timber merchant Abraham Liberman, who had died of natural causes, provided an opportunity to mourn the impending extinction of the town’s Jewish community.

The liquidation of the Jewish community in Kosow Lacki began on 22 September 1942, when early in the morning Germans, Ukrainian guards and the Polish fire brigade cordoned off the town. SS officers ordered the Judenrat and Jewish Police to gather all the Jews in the market place, excluding the families of the labour camp craftsmen, in the building where the Judenrat met. SS and Ukrainian auxiliaries accompanied by Jewish Police members on a house to house search for those in hiding, shooting any of those they found. Other Jews, including a doctor, a female dentist and at least two refugees from Warsaw, committed suicide. Approximately 150 ghetto residents were killed trying to flee and were buried in a mass grave at the Jewish cemetery. The next day, the SS searched Polish houses throughout the town and in the surrounding countryside, killing any Jews they discovered there. Disagreement exists over how the 3,800 Jews from Kosow Lacki’s ghetto were transported to the Treblinka death camp. In some accounts they were escorted to the railway station and loaded onto wagons; in another account the Jews from Kosow Lacki were marched to Treblinka on foot. The Treblinka labour camp craftsmen families were relocated to two narrow streets in an impoverished part of the town and were ordered not to leave under penalty of death. Over the course of the next month, the Germans encouraged Jews who had escaped previous round-ups to return to Kosow Lacki, promising them, they would not be deported.

On 28 October 1942, Kosow Lacki was announced to be one of six remaining Judenstadt (Jewish Town) in the Warsaw district Between 50 and 100 people came out of hiding and joined the craftsmen families. They were the target of further SS round-ups in December 1942, which once again spared those families whose husbands and sons who worked at the Treblinka labour camp. The residents of the ghetto became subjected to random violence perpetrated by the SS, when one evening shortly after the second round-up, a group of SS arrived ‘to have fun by shooting Jewish men.’ On what subsequently became known as ‘Yankel Evening,’ the SS caught several young Jewish men, including five named Yankel, and chopped their heads off with axes. In February 1943, an SS unit took Kosow Lacki’s remaining Jews to the Treblinka labour camp, with the promise to reunite them with their husbands and sons. Not more than 50 of Kosow Lacki’s Jews survived the war. Of those who were deported to the Treblinka labour camp, only Szymon Cegel is known to have escaped. The other Jews from the ghetto, who survived, did so, mainly thanks to the rescue efforts by Poles in the nearby countryside. Tragically, as many as 11 Jews who had survived the war, were killed in the immediate aftermath along with Poles, when the non-communist Underground blew up Kosow Lacki’s Citizen Militia building.

Sources: The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Photograph – Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2015