Łódź (Litzmannstadt)

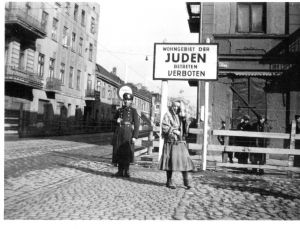

Litzmannstadt Ghetto Entrance

Lodz is situated 85 miles south-west of Warsaw. Its textile industry was the largest during interwar Poland. In 1931, its 604,629 residents included among others 356,987 Poles, 191,720 Jews and 53,562 Germans. On the eve of the Second World War, its Jewish community, numbering approximately 235,000 was the second largest in Europe.

Upon occupying Lodz on 8 September 1939, the Germans unleashed three months of sustained anti-Jewish violence, including seizing Jews for forced labour, plundering and confiscating Jewish property, executing Jews and deporting to concentration camps, hundreds of the city’s Jewish political, business and cultural elite. On 10 December 1939, Friedrich Ubelhor, Regierungsprasident in Kalisch, secretly ordered the German authorities to plan a ‘transitional ‘measure: a closed ghetto to imprison the Jews until their expulsion to the General Gouvernement could take place. On 8 February 1940, SS- Brigadeführer Johannes Schafer, the Lodz Polizeiprasident, publically announced the establishment of a ghetto in northern Lodz, ultimately on 1.6 square miles in the Baluty, Stare Miasto (Old Town), and Marysin neighbourhoods. Ethnic Germans and Poles had until 30 April 1940, to vacate their residences there. Given until 19 April 1940, to move into the ghetto, Jews could bring one suitcase of clothing, linens, photographs, and a bed. Chaim Mordechai Rumlowski was appointed by the German authorities as head of the Jewish Council of Elders on 13-14 October 1939. He was ordered to establish a Jewish police force (Judischer Ordnungsdienst), which he did on 1 May 1940. The headquarters was located on 1 Lutomierska Street and the commander was Leon Rozenblat. The Jewish ghetto police numbered some 1,200 men in 1943, and was charged with keeping order in the ghetto, fighting the black market and taking part in the deportation ‘Aktions’ of the ghetto residents to the death camps at Chelmno and Auschwitz.

Starting on 1 March 1940, the SS and police, impatient with the speed of the transfer, arrested Poles still living in the ghetto. The Germans released some 600 Poles designating them to move into Polish areas established in southern Lodz and filling their places with Jews. Approximately 200 Jews were shot dead during the evacuations, mostly on 7-8 March 1940, which became known locally as ‘Bloody Thursday’. Some 160 Jews were executed in the Lucmierz Forest, near Zgierz, whilst some 400 to 500 Jewish prisoners were expelled to the General Gouvernement.

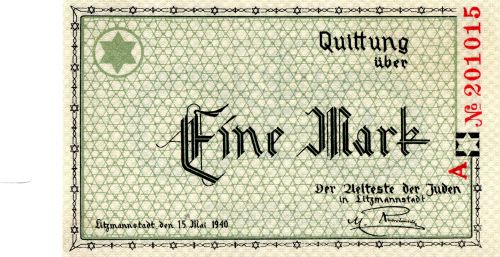

From the autumn of 1941, Jews from beyond Lodz were consolidated in the ghetto: 2,900 from the Kujawy region, 19,954 from Prague, Vienna, Luxembourg, Berlin, Dusseldorf, Emden, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg and Cologne and 18,500 from locations near Lodz. Also from 5-9 November 1941, 5,007 Roma Gypsies arrived from Burgenland, Austria. Additionally, 2,306 children were born in the ghetto. The total number of people residing in the ghetto amounted to approximately 210, 000. The German city administrators further exacerbated conditions in the ghetto, initially they moved slowly on Chaim Rumkowski’s requests made in March and April 1940, to establish factories thus enabling the Jews to finance the ghetto by extracting moveable wealth from the Jews. The EWG debited Rumkowski’s account for requests he made to ease living conditions, such as the provision of medical equipment and furnishings in a modern pre-war public health clinic and for three wooden pedestrian bridges constructed in July 1940, over the roads excluded from the ghetto, at a cost of 60,000 Reichsmark (RM). To resolve the ghetto’s growing debt, the EWG ordered the Jews in June 1940 to exchange their convertible currency at a ghetto bank for vouchers. The Jews called the ghetto currency Chaimki or Rumki, because they carried Rumkowski’s name. A special Kripo unit, the so called Kriminalpolizei Sonderkommissariat Getto commanded by Bruno Obersteiner and Wilhelm Neumann, established offices in the ghetto in May 1940 to facilitate searches for items the EWG and the Jewish administration ordered the Jews to surrender. In July 1940, Rumkowski acting on orders from the Gestapo and EWG, created a special division of the Jewish police, the Sonderabteilung, to assist in searches undertaken by the Kripo. From August 1940, a second ghetto bank assessed and purchased for ghetto currency Jewish –owned valuables, including paintings jewels, leather goods, clothing and linens. These policies rapidly made the ghetto inhabitants much poorer, because they forced almost all the Jews, except possibly the 7,000 or so who were employed on 25 June 1940, to sell possessions in order to survive. By August 1940, only 52.2 percent of the ghetto residents could afford to buy food. During August 1940, Rumkowski called on German forces to dispel riots over food and distribute potatoes to the most impoverished. On 19 September 1940, he declared his administration financially incapable of feeding the impoverished and requested a 2 million RM loan. German officials caused looting by suspending food deliveries into the ghetto for two weeks to extract additional valuables.

Litzmannstadt - Ghetto Currency

Since Hans Frank refused to resettle the Lodz Jews into the General Gouvernement, on 18 October 1940, the municipal authorities acknowledged that the ghetto would continue to exist. They approved a 3 million RM loan to provision the ghetto and to develop workshops there. To cut costs, they ordered that the Jews receive prison rations, from the worst of the available food supply, and insisted that only the most productive workers be awarded supplemental rations. Biebow’s office became an autonomous division, the Gettoverwaltung (Ghetto Administration, GV), which reported directly to the Mayor. Biebow elevated the ghetto Kripo, giving it identical access as the Gestapo to his meetings with the Jewish administrators. Police authorities insisted the ghetto be surrounded with an elaborate ‘fire break,’ or a no-man’s land. Some neighbourhoods were razed to the ground beginning in late 1940. Guard booths and electric lights were installed in the vacant expanse. However, plans to install searchlights and to build watchtowers were never implemented, in part because the subsequent success of industrial expansion eased concerns about security by the spring of 1941 and may also have diminished retributive police terror. By July 1942, the Gettoverwaltung oversaw 74 ghetto workshops, officially called ‘Arbeitsressorte’ (work sections) but popularly known as’ ressorts’. Some 90 percent of all production was for the Wehrmacht. German department stores placed most of the remaining orders. A small pre-war railway depot, the Radogoszcz station located in the ghetto, was expanded to deliver machinery and raw materials and to dispatch finished products, including clothing, shoes, carpets, furniture, telephone equipment, toys and paper bags.

Chaim Rumkowski built a vast bureaucracy, numbering more than 13,000 people in August 1942, to oversee factories, housing, food supply, health care, and sanitation. In August 1940, he opened soup kitchens for the poor. In October 1940, he implemented a promised welfare system, sending monthly stipends of 7 to 10 Marks to 82,000 children and adults. However, the Jewish administration struggled over how to apportion the limited food the Germans sent into the ghetto, which likely amounted in most food categories to half a prisoner’s ration. A 15 percent surcharge for food purchased on credit and a 15 percent fee to transfer food into the ghetto added costs to the few provisions the ghetto received. Rumkowski responded to the food shortages by demanding the Jews worked harder to pay for their maintenance and by instituting increasingly authoritarian measures. In December 1940, he ordered the Jewish administration to take over private soup kitchens and restaurants and to ration food. In the spring of 1941, he liquidated the pioneer training camps of young Zionists and seized their farms in Marysin. To eliminate speculation, he ordered periodic crackdowns and arrests of smugglers and those engaged in black market activities.

Within the ghetto, the shrinking economy exposed divisions in the Jewish community. During January 1941, Rumkowski announced a more equitable distribution of the bread ration by discontinuing a 600 grams daily supplemental ration for manual workers to increase the general population’s ration from 300 to 400 grams. In February 1941, clandestine political groups protested against this decision with a carpenters’ strike. Most strikers returned to work after Rumkowski offered 580 grams of meat and 2 kilograms of potatoes to ‘ressort’ workers. The Jewish police put down the remaining opposition. In March 1941, 700 welfare recipients demanded increases in relief payments and decreases in the prices of food. The western Jews from the Reich, in particular, found adjusting to the harsh reality of life in the ‘east’ very difficult, and approximately half of them, never found employment.

Material conditions for the Jews continued to decline, just as the daily food rations diminished – about 1,800 calories in the first months of the ghetto’s existence, decreased to 600 calories by mid-1942. Most Jews subsisted on a daily bowl of watery cabbage or potato soup, a piece of bread, and a small evening snack of radish greens or potato peels. Paltry heating and restrictions on electricity use in residences, forced almost everyone to eat collectively in soup kitchens, to curtail the laundering of clothing and linens in hot water, and to eat unheated evening meals – factors that contributed to outbreaks of typhus and dysentery. In 1942, the annual death toll peaked at 18,000. The Jews that had been deported from the Reich featured heavily amongst the victims. Because Rumkowski had centralized so much authority for day-to-day operations within the ghetto in his hands, this portrayed himself as the ghetto’s supreme ruler and he boasted of Jewish autonomy in the ghetto. This resulted in many people blaming him for their plight. Some Jews maintained he had established a system of patronage and privilege, in which the elite of the ghetto and the ghetto leadership and they benefitted from ‘substantial supplemental rations, while the rest were swelling up and dying of hunger.’ Other Jews privately bemoaned Rumkowski’s incompetence in economic affairs and castigated him for silencing opponents by ordering them conscripted for forced labour outside of the ghetto, among the 13,000 or so people sent to 160 forced labour camps, established mainly near Poznan, for the construction of the Frankfurt on the Oder – Poznan- Lodz autobahn.

Despite the appalling living conditions, the ghetto sustained a variety of cultural activities. Until September 1942, religious observance continued in 27 Batei Midrash. Poets, writers, and musicians presented works in soup kitchens and at a cultural hall, opened in March1941 by the Jewish administration. Between June 1940 and October 1941, 14,798 children attended 45 primary and 2 secondary schools. The cultural events enabled individuals to forget their isolation, hunger and despair for a brief time. The schools served one subsidized meal a day, thus providing students with important nutritional sustenance. A Department of Archives established in November 1940, wrote a chronicle of events in the ghetto. Though rarely critical of Rumkowski, it remains an important source for understanding daily life in the ghetto.

Starting in the autumn of 1941, the German authorities started to debate the fate of the Lodz ghetto. Local and regional officials, including Biebow, Ubelhor, and Greiser, had made money from the ghetto and argued for its continued existence, based on its contributions to war production. They found powerful allies in those responsible for war production, most notably Albert Speer, the Reich Minister for Armaments and War Production, and they managed to fight off Himmler’s plans to liquidate the ghetto. They agreed to shield the ghetto’s productive capacities, which netted official profits from March 1942, by targeting first for ‘resettlement’ those Jews whom they classed as ‘non-productive.’ Biebow had adopted such a policy from early in 1942, while participating in the liquidation of the provincial ghettos, by retaining circa 18,500 mostly male craftsmen and labourers for work in the Lodz ghetto.

In March 1942, Rumkowski informed the Jews of Lodz, ‘A new rule has been introduced…. Only working people can stay in the ghetto,’ and in April 1942 he trumpeted employment as a ‘guarantee of peace.’ The Jewish administration attempted to insulate the Jews from German violence by organising the deportations. Rumkowski appointed a commission of five to draw up deportation lists; the commission in turn sent notices to those slated for ‘resettlement’; teachers and others from the Jewish administration filled out documentation at assembly points. Those who failed to report were brought to the assembly points by the Jewish Police. From April 1942, the German authorities intervened, ordering the non-working population over the age of 10 to report for a cursory medical examination, conducted by a commission of German doctors, members of the Gestapo, and Jewish physicians, to determine which of the unemployed were fit for work, and those that were fit to be ‘resettled.’ The examinations likely played some role in the Jewish administration’s decision in the spring of 1942 to expand factory employment to include tens of thousands of young people aged 8 to 14 in apprenticeship programmes.

In Lodz, the first deportation ‘Aktion’ took place from 21 December 1941, to 15 May 1942. On 7 January 1942, the first of five thousand Gypsies incarcerated in the Lodz ghetto that were housed in a Gypsy camp in the quarter of Brzezinska, Towianskiego, Starosikawska and Glowackiego Streets, were taken by truck to the Chelmno nad Nerem death camp. All of them were murdered in gas-vans, and amongst this transport was a Jewish doctor Dr. Fickelburg, and a Jewish nurse, whose name is unknown. They had been working as a medical team in the Gypsy camp, and they shared the same fate as the Gypsies. The Jews initially deported from Lodz left the Radogoszcz station in 55 trains in three deportation waves, the first during 16 January 1942 – 29 January 1942, the second between 22 February till the 22 April 1942, and the third on 2 May 1942 till the 15 May 1942. A total of 57,064 Jews from the Lodz ghetto, including 10,943 Jews from Western Europe were gassed at Chelmno.

The second deportation ‘Aktion’ which took place during 1-2 September 1942, and between 5 – 12 September 1942, first targeted the sick at the ghetto’s hospitals. On 4 September 1942, Rumkowski appealed to the Jews to hand over their children and elderly residents to save themselves. The German authorities imposed an ‘Allgemeine Gehsperre’ (General Curfew), forbidding ghetto residents from leaving their homes for five days, to make it easier for the Jewish Police and firemen to locate the victims. On 7 September 1942, the SS and Kripo stepped in to oversee the searches. Some 164 to 570 people were shot on the spot; 15,682 children, elderly, and infirm Jews were sent to the gas-vans at Chelmno death camp. The SS ordered the ghetto’s children and elderly surrendered, and as Rumkowsi knew, at least from the summer of 1942, that the Germans were gassing Jews in Chelmno, most survivors consider his actions during the ‘Allgemeine Gehsperre’ as unforgiveable. A few survivors maintain the Germans determined the scope and timing of the deportations and believe Rumkowski acted realistically, according to the context and morality of the time, by attempting to make the Jewish labour force indispensible to the Germans, while capitulating to their demands for population reductions, in a desperate effort to save a part of the Jewish population. They attribute him with formulating a policy that enabled the Lodz ghetto to survive beyond any other ghetto in German occupied Poland, and as a result thus increasing the survival chances for many thousands of Jews.

After the initial deportations, the ghetto resembled more of a labour camp. Some 73,782 Jews were employed at 101 ‘ressorts,’ which were monitored directly by Biebow and officials from the Gettoverwaltung. The orphanages, old-age homes, and hospitals were closed. Biebow ordered all Yiddish and Hebrew signs replaced with German signs and he suspended the rabbinate. Biebow also diminished Rumkowski’s authority by reducing the size of the Jewish ghetto administration and transferring responsibility for factory production and food supply to Jews with close ties to the Gestapo and Kripo.

Some welfare schemes were once again established, though somewhat transformed to accommodate the new realities of ghetto life. Malnourished workers received eight weeks of bakery employment to provide them with extra bread rations. Rest homes provided weeklong holidays with increased rations, to 11,706 workers before Biebow closed them on 25 August 1943. Rumkowski successfully appealed to ghetto residents to adopt 2,000 children orphaned by the deportations. He also served as a chaplain at marriages, which the German authorities required them to be civil ceremonies.

In mid-February 1944, Arthur Greiser accepted Himmler’s demands for a gradual liquidation of the Litzmannstadt ghetto, ordering in March 1944, the Chelmno death camp to become operational again. At the same time, some 1,600 Jews were deported to forced labour camps in Czestochowa and Skarzysko- Kamienna. The military defeats experience by the German army in April – May 1944, ended whatever hesitation Himmler may have had regarding the liquidation of the ghetto. On 15 June 1944, Gunther Fuchs was recalled to Lodz to oversee the deportations, and Bradfisch demanded that 3,000 Jews be deported weekly, ostensibly to clear war damage in the Reich.

Between 23 June 1944 and 14 July 1944, ten transports carried 7,196 Jews to their deaths in the Chelmno death camp, now situated in the ‘Waldlager,’ gas-vans continued to operate as the principle means of destruction. Fears that the Red Army would capture Chelmno, meant the deportations were suspended for a short time. They began anew on 9 August 1944 and lasted until 29 August 1944, this time to the Auschwitz – Birkenau concentration camp. Between 65,000 and 67,000 Jews from the Lodz ghetto died in the gas chambers at Auschwitz, and this included Chaim Mordechai Rumkowski and his family, who were transported to Auschwitz on 28 August 1944, where they perished.

Approximately 1,000 to 1,500 people who had evaded the deportations, remained behind in the ghetto to clear and sort the possessions of the victims and to dismantle some of its workshops. On 21 October 1944, 500 inmates were sent to the Ravensbruck concentration camp and the Konigswurstenhausen labour camp near Berlin. In January 1945, as the Red Army approached Lodz, the Germans ordered a brigade of ghetto inmates to dig mass graves at the Jewish cemetery, but on 17 January 1945, the Jews hid, rather than assemble for evacuation. Approximately 877 Jews were still hiding in the ghetto when the Red Army drove the Germans out on 19 January 1945.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Julian Baranowski, The Lodz Ghetto 1940 -1944, Vademecum, Archiwum Panstwowe W Lodzi & Bilbo, Lodz, 1999.

Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, William Collins Sons and Co Ltd, London, 1986

Photograph and Currency Image – Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2019

Arthur Greiser, Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter of the Warthegau, officially lobbied for Lodz to be incorporated into the Warthegau on 9 November 1939, and because he was anxious to Germanise the city by resettling Reich and ethnic Germans there, the German authorities initially planned to expel the Jews, rather than force them to live in a ghetto. From 11 December 1939, German police, security officials, and local ethnic Germans organised in a Selbstschutz unit, and German civilians, including Hitler- Jugend (Youth) members brought from the Reich, began deporting Jews and some Poles into the General Gouvernement. Plans called for the expulsion of 30,000 Jews and 30,000 Poles from Lodz, but protests from Hans Frank, head of the General Gouvernement, suspended the deportations on 16 December 1939, after the transfer of 25,374 people had taken place. It was likely that the Jews were over-represented in the deportations because members of the Hitler –Jugend had targeted them specifically. Ongoing anti-Semitic terror and rumours of a total expulsion prompted another 60,000 to 75,000 Jews to leave Lodz on their own accord.

During March and April 1940, the German authorities encircled the ghetto with a barbed-wire and wooden fence. On 30 April 1940, the gates were closed on its 163,777 inhabitants and on 10 May 1940, the Schutzpolizei (Schupo) and its auxiliaries, posted at 50 –to 100 –meter intervals along the outside of the 6.8 mile ghetto perimeter, received orders to shoot Jews approaching the fence, without warning. About 180 Jews were killed for being too close to the fence.

In April 1940, the Germans changed the name of Lodz to Litzmannstadt, and this applied to the ghetto as well. Karl Marder and Werner Ventzky, the city’s Oberburgermeister and Burgermeister, were the chief administrative and economic officers of the ghetto. They initially charged the Ernahrungs-und Wirtschaftsamt Haupstelle (Food Supplies and Economy Department) with day –to-day responsibility for the ghetto. The department in turn created a Ghetto division, officially called the Ernahrungs-und Wirtschaftstelle Getto (EWG), led from May 1940 by Hans Biebow, a coffee merchant from Bremen. The Schutzpolizei Kripo and Gestapo exercised police authority over the ghetto. In January 1942, SS- Sturmbannführer Dr. Otto Bradfisch replaced the first commander of the Litzmannstadt Gestapo, SS- Hauptsturmführer Dr. Robert Schefe. In August 1942, Otto Bradfisch also assumed Werner Ventzky’s position. Through 1943, SS- Obersturmführer Gunther Fuchs headed the Gestapo’s section for Jewish matters.

Conditions in the ghetto were appalling. Because the Jewish Council of Elders had designated the housing in Marysin, a more rural, middle-class neighbourhood, mainly for schools, old-age homes, and an orphanage, almost all the Jews were squeezed into approximately 2,300 homes located in less than one square mile in the Baluty and Old Town areas. The two neigbourhoods were notorious slums, whose mostly 100-year old wooden houses lacked central plumbing. The exclusion from the ghetto of Nowomiejska – Zgierz and Limanowsi Streets, throughways left open to non-Jewish traffic, made movement within the ghetto difficult. Initially, the Jews crossed the streets at specific gates, only at designated times.

The workers toiled for 10 -14 hours a day in poorly ventilated, overcrowded workshops, earning wages on a piece-work basis. The wages were kept low, because the Gau authorities took 35 percent off the top, the Gettoverwaltung another 30 percent, and the Jewish Council of Elders another 10 percent. The most skilled worker received at best 4 ghetto Marks daily. Non-skilled workers received 1 Mark. Workers rapidly produced large quantities of finished goods, including almost 5,000 complete sets of Wehrmacht uniforms within a week. Such output fueled industrial expansion, but never allowed for full employment, and by March 1942, the ‘ressorts’ employed 53,000 workers.