Radom

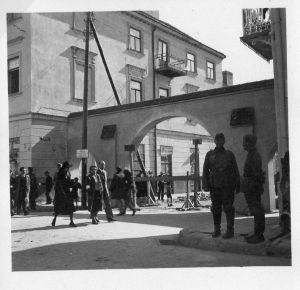

Radom Ghetto Entrance

Radom is a city in central Poland, located 62 miles south of Warsaw, and it stands on the banks of the River Mleczna. Approximately 30,000 Jews were living in Radom when the Second World War started in September 1939. This figure represented about one –third of the city’s population and most of the Jews earned their living as craftsmen, small-scale industry, and commerce, especially in the garment, food, construction, and metal industries. They were supported by Jewish trade unions, most of which were dominated by the Bund and Po’alei Zion; Jewish workers also received assistance from a savings-and-loan fund supported by the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) and from a number of Jewish banks that were active in the city. Radom had traditional welfare and charity institutions and the community supplied the unemployed with financial aid. A TOZ (Society for the Protection of the Health of the Jewish Population in Poland) chapter in Radom provided Jewish children with medical treatment, held summer camps for about 100 children, and supported Radom’s Jewish hospital.

Radom’s Jewish schools included a Yavne and a Horev school, as well as an ORT (The Institute for Vocational Guidance and Training) vocational training school. Hasidism was very influential in Radom, and a number of prayer houses were active. Radom had Zionist parties and youth movements, which established pioneer training facilities, as well as Agudath Israel and the Bund. Many Jewish workers were members of the illegal Polish Communist Party. Each Party maintained a few libraries and from time to time, periodicals were published. During the 1920’s and 1930’s, a number of Jews were murdered in a series of anti-Semitic incidents that took place in Radom.

After the Germans invaded Poland, many of the city’s Jews, including community leaders and public figures, attempted to flee to the east, towards the Soviet lines. On 8 September 1939, the German army occupied Radom, and a few days later, SS forces also entered the city. They soon began to seize Jews for forced labour and terrorise them. In late September 1939, the military governor appointed fifty community leaders to serve on a temporary Jewish Council, a Judenrat, headed by Yaakov Goldenberg. Yosef Diamant, a long-time Jewish activist, was appointed his deputy. On 4 October 1939, the council was ordered to collect a ransom payment and provide the Germans with clothing and bedding. The Germans meanwhile appropriated Jewish property, placing in charge German custodians, although many Jewish business owners continued to work in their own businesses for paltry wages. Jews who lived in certain areas of the city were forcibly evicted from their dwellings, which were then inhabited by Germans.

In December 1939, a twenty-four member Judenrat was established that also served as the district Judenrat (Oberjudenrat), with Yosef Diamant appointed to head the organisation. The Judenrat employed about 500 people and set up numerous departments, including a housing department, which was responsible for finding homes for the Jews evicted from their homes, and the refugees who had arrived from Warsaw, Lodz, Przytyk and Kalisz. They also established an employment bureau which was responsible for delivering Jews for forced labour. In the first few months of the occupation, the Germans demanded 80 to 100 workers daily; later the number rose to 500 to 600, and in 1940, the number increased to between 1,000 and 1,400 workers daily. The Judenrat also established a health committee which strove to prevent the spread of typhus. In April 1940, the Jewish hospital was expanded and placed under the direction of Dr Kleinberger, and a dental clinic, a sterilisation room, and an x-ray clinic were opened. The Germans had all of the patients hospitalised in the General Hospital in Radom transferred to the Jewish hospital, which was turned into a centre to fight the spread of contagious diseases in the city. In the spring of 1940, the Jewish Self Help (JSS) established a branch in Radom to help with welfare and opened three public soup kitchens in the city, which distributed more than 3,700 meals a day for free or a token sum. In July 1940, the JSS established three additional public soup kitchens that distributed free meals to children.

In April 1940, the Germans carried out a ‘political Aktion’ against public figures in Radom, during which eighteen Jews, most of whom had been members of Po’alei Zion Left, were executed. In July 1940, the Germans completed the confiscation of all Jewish property and its transfer to German administration. Also in the summer of 1940, the Judenrat were forced to recruit Jews for forced-labour camps in the Lublin area. On 20 August 1940, the first group, of some 2,000 workers was dispatched to the camps, which were employed on digging fortifications and anti-tank ditches in the Belzec area. The Judenrat strove to send these workers food and clothing, but nearly all of them perished. During the following months, two additional groups were sent to labour camps near Radom, Kruszyna and Jedlinsk. The majority of these workers did not survive the terrible conditions, whilst those who were able to return to Radom, were in terrible health, and had to be admitted into the Jewish hospital for treatment.

In December 1940, Hans Frank, the Governor-General of the Generalgouvernement ordered the deportation of 10,000 Jews from Radom, to other locations, but the Judenrat were able to drastically reduce this number to 1,840 Jews who were in fact deported on 18 December 1940. But, the Germans, in early December 1940, some 2,000 Jews arrived in Radom from Cracow. On the eve of the establishment of the ghetto in Radom, the Jewish population stood at approximately 32,000.

In March 1941, the Germans issued an order to concentrate the Jews of Radom into two ghettos several miles apart. Some 27,000 Jews were moved into the ghetto that was located in the centre of the town, while some 5,000 Jews were concentrated in the second ghetto in the poor neighbourhood of Glinice. On 1 April 1941, the Judenrat was ordered to establish a Jewish Order Service, and Joachim Geiger was appointed to head it. Young men over the age of twenty-one, who had served in the Polish army were encouraged to join. On 7 April 1941, the concentration of the Jews in both ghettos was completed and the ghettos were sealed, its borders marked by the buildings located on the ghetto’s perimeter. The large ghetto had thirteen gates with large signs posted that read: ‘Danger – Contagious diseases – No Entry.’ Although the small ghetto was less crowded, most Jews preferred to live in the large ghetto, which contained the Judenrat, and the welfare institutions.

Clandestine educational activities were organised in the ghetto. Teachers and young graduates of the Jewish high school organised activities for the kindergarten-aged children. In November 1941, engineers and technicians in the ghetto organised courses for vocational training in metalwork, mechanics, and other subjects, which enabled Jewish teenagers to find work inside and outside of the ghetto. Most of the courses were held in the small ghetto. The Jewish hospital was located in the large ghetto, while the old-age people’s home and orphanage remained outside of the ghettos. A Christian old-peoples home and a shelter for the mentally-ill operated inside the large ghetto. The most serious health issue faced by the ghetto’s residents was typhus epidemics and by autumn 1942, some 3,000 to 4,000 Jews had been hospitalised, and many more were treated in their homes.

On 19 February 1942, the Germans swept into the ghetto and murdered several dozen people. They also carried out a ‘political Aktion’ arresting and deporting to Auschwitz concentration camp about forty community leaders, who had been activists in various left-wing parties, using lists that had been prepared beforehand. This was followed on 28 April 1942, with another similar ‘Aktion’ that became known locally as ‘Bloody Wednesday.’ This operation carried out by the SS, was intended to undermine the Jewish leadership in Radom, and to prevent resistance during the forthcoming liquidation of the ghetto. Members of the Gestapo led by Richard Schoeggl and Paul Fuchs entered the ghetto and seized a large number of Jews in their homes. Some were murdered on the spot, while others were taken to the local prison and subsequently onto Auschwitz, where they arrived on 30 April 1942. Whilst approximately 70 Jews were murdered in the ghetto, among those taken to Auschwitz was Yosef Diamant, the head of the Judenrat, and three of his assistants. The Germans ordered the formation of a new Judenrat and Ludwig Fasman was appointed to head it.

After this murder operation in April 1942, rumours spread in the ghetto, regarding the possibility of deportations in Radom, following news of the deportation in March of the Jews in Lublin. The demand for jobs rose, as the ghetto inhabitants believed that workers with a permit, would be exempt from the deadly deportations. In early summer 1942, SS- Hauptsturm

Wilhem Blum was sent to Radom from Lublin to plan and carry out the deportation of the Jews from the city, in conjunction with SS und Polizeiführer Radom Herbert Böttcher. On the night of 5 August 1942, the SS encircled the small ghetto and a brutal selection was carried out at a site near the railroad tracks by SS officers, including öttcher, Blum, Franz Schippers, and Adolf Feucht, together with Ukrainian –SS under the command of Erich Kapke. Following the selection, the SS officers and Ukrainian-SS transferred about 800 Jews with work permits to the large ghetto. About 600 children and elderly Jews were murdered during the selection, and the rest were deported to the Treblinka death camp, together with about 2,000 Jews from the large ghetto. Approximately 100 young Jews with work permits were given the task of burying those murdered near the Lenz factory and collecting their belongings, and storing it in the empty Korona factory.

On 16 August 1942, all the gates in the large ghetto were blocked, and the ghetto was encircled by German and Ukrainian-SS forces. On the night of 16 August 1942, another ‘Aktion’ was carried out under the command of öttcher and Blum, and approximately 1,000 Jews were killed in the ghetto. Jews who resisted or were found in hiding were shot on the spot. A group of children was murdered with hand grenades in a slaughterhouse by SS- Hauptschar. The rest of the ghetto’s inhabitants were rounded up in the old city square and put through a selection by SS officers under Feucht’s command. About 4,000 people with work permits were assigned to forced labour. The rest some 18,000 people were deported on 17 August 1942, to the Treblinka death camp. Fifty patients in the Jewish hospital were murdered in specially dug pits prepared near the ghetto. These deportations in August 1942 saw some 30,000 Jews from Radom deported to Treblinka, where the vast majority were murdered in the gas chambers.

Following these mass deportations, approximately 200 Jewish workers were given the task of collecting and sorting the Jews’ belongings, some of which were sold or distributed for free among the Polish residents of Radom. The belongings of Jews who had also been deported to Treblinka, were later shipped to the warehouse for Jewish property in Radom. The ghetto population gradually increased, as Jews who had sought refuge outside of the ghetto during the mass deportations returned. About 5,000 Jewish workers and their families, along with 300 members of the Jewish Order Service and their families, were transferred to the small ghetto. Three members of the Judenrat, including Dr Ludwig Fasman, who stayed on as head of the Judenrat, were also transferred into the small ghetto. The Jews of Radom were now concentrated in the large ghetto and the small ghetto, which were now designated labour camps.

Immediately after the mass deportations in August 1942, an Underground group with thirty members was formed under the command of the Bornstein brothers – Zalman, Leib and Yonah. They were able to make contact with the Polish Underground and obtained a few firearms. They sought to join the partisans rather than fight the Germans in the ghetto and in late October 1942, some of the group made its way to the Swietokrzyska forest but a number of them were killed during a German manhunt. The survivors returned to the ghetto.

Radom 2004

On 3 December 1942, a Ukrainian –SS guard unit and a group of SS soldiers deported about 800 Jews from the large ghetto to a ghetto that had been re-established at Szydlowiec. A number of Jews were killed along the way by the guards, and most of the rest perished. On 13 January 1943, approximately 1,500 Jews whose names appeared on a list of people who had requested visas for Palestine, or who had received permits to emigrate, were deported to the Treblinka death camp, in a murder operation that was known as the ‘Palestine Aktion.’ On 20 January the Germans murdered a group of Jews who were accused of sabotage at their place of work.

In early December 1942, a group of seventy-six Jews, including women and children , fled from the ghetto and established contact with the Armia Ludowa in the Radom District. The escapees reached the Polish partisan group that was active in the area, but the Germans surrounded them, and they were probably killed, but their true fate is unknown.

In January 1943, Dr. Ludwig Fasman was arrested and deported to Auschwitz concentration camp and Nachum Shenderovich was appointed to take his place. But this was short lived for on 1 May 1943, the Gestapo arrested the last remaining members of the Judenrat and sent them to a labour camp near Wolanow. Most were murdered, and the rest including Shenderovich were subsequently deported to Auschwitz. The head of the Jewish Order Service Leon Sytner was appointed as the last head of the Judenrat and by this time the ghettos were established as slave labour camp under the command of Franz Schippers. The main place of employment was the Wytwornia armaments factory, where approximately 1,000 Jews worked. Another group, mainly women, worked in the Korona warehouses, sorting the belongings of those deported and murdered.

On 8 November 1943, the Germans liquidated the small ghetto and about 100 women, and children were shot and the rest were transferred to a dilapidated camp on Szkolna Street. 200 Jewish workers were also transferred to Skarzysko- Kamienna and Plonki to work in arms factories. In the Szkolna camp around 3,000 men women and children were forced to work for the Germans, the Jewish head of this camp was Yechiel Friedman. When the Szkolna camp was liquidated on 26 July 1944, the former inmates of Kolejowa 18 camp, were forced to march to Tomaszow-Mazowiecki, and from there onto Auschwitz-Birkenau. After a selection the women remained in Auschwitz, whilst the men were deported to the Reich near Stuttgart, for forced labour.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2012

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

D. Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle, Henry Holt and Company, New York1989

J. Schelvis, Sobibor – A History of a Nazi Death Camp, Berg, Oxford and New York 2007

Photographs - Tall Trees Archive and Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018