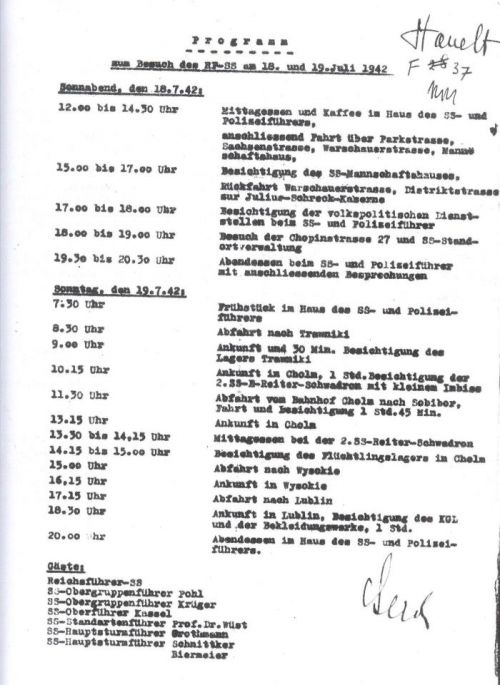

Trawniki Labour Camp

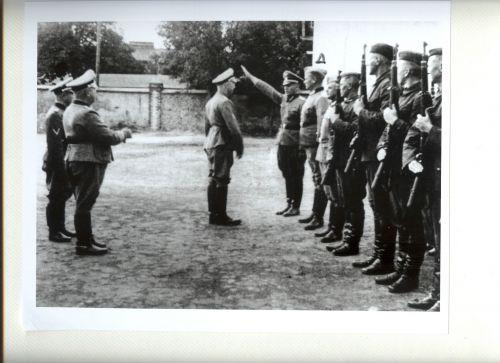

SS Officer Lehnert in Trawniki

Less than two weeks after the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, German SS and police authorities in the Lublin District, acting on the orders of the SS-

In September 1941, following Globocnik’s appointment to the post of Commissioner for the Establishment of SS and Police Bases in the New Eastern Territory, Globocnik transformed the facility into a training camp for auxiliary police personnel to maintain security in support of German rule over the ‘wild East.’ Globocnik staff recruited captured Soviet Prisoners of War who, after being trained in Trawniki, entered the Guard Forces (Wachmannschaften) of the SS und Polizeiführer in the Lublin District. The basis to recruit these so-

The first 2,500 auxiliary police guards were inducted and trained between September 1941 and September 1942. Virtually all of them were Soviet Prisoners of War. As German military reverses and the murderous treatment of the Soviet Prisoners of War dried up the supply of suitable Soviet soldiers in the autumn of 1942, Streibel’s men conscripted civilians, primarily young Ukrainians residing in Galicia, Wolhynia, Podolia, and the Lublin District. When Globocnik left Lublin in September 1943, he reported that 3,700 Wachmanner were serving in the Trawniki system, in fact, more than 4,750 identification numbers had been issued by this time. Approximately 5,082 men were trained at Trawniki between 1941 and 1944. They were organized into two battalions under the command of SS-

Deployment in the operations of the Aktion Reinhardt, the name given to the mass murder of Polish Jewry became a key function of the Trawniki-

In 1942, Trawniki served as a transit camp for local Jews, for example after an early April ‘selection’ of those incapable of work in the transit ghetto of Piaski, located about 6 miles away. The Ukrainian ‘Wachmanner’ escorted several hundred Polish, German, and Austrian Jews from Piaski to Trawniki. Scheduled for deportation to Belzec the following day, many of the victims were locked up in a large barnlike structure overnight. Between 200 and 300 died from suffocation, their bodies were tossed the next morning into the freight cars destined for Belzec.

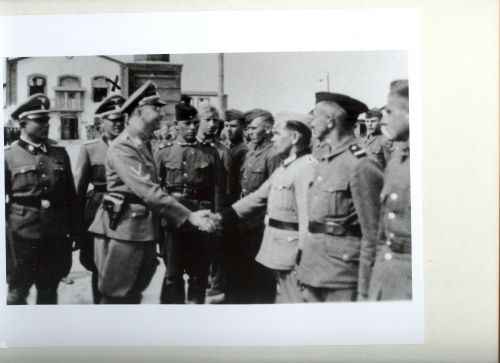

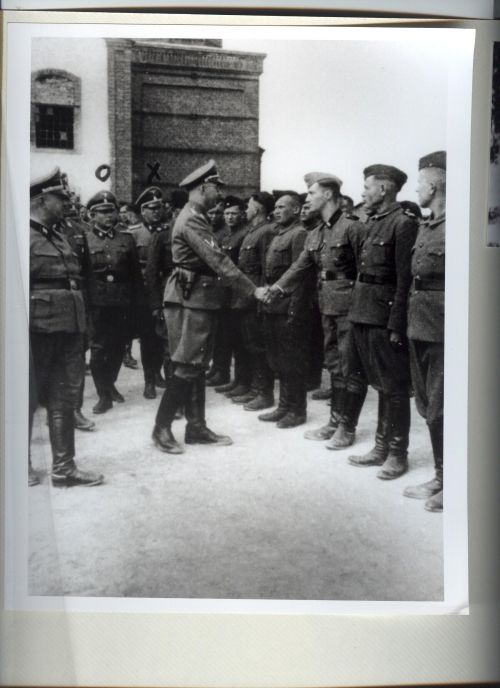

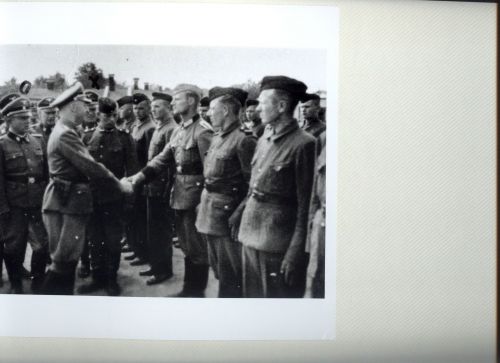

Trawniki - July 1942: August Frank (third from left confers with Odilo Globocnik

During the summer of 1942, Trawniki also began to serve as a forced labour camp for Jews (Zwangsarbeitslager fur Juden). Under the auspices of ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ the SS and police constructed a labour camp adjacent to the training camp, separated only by the original stone wall that surrounded the abandoned sugar factory. The appearance of a Jewish workforce at Trawniki coincided with the establishment of procedures for disposing of some of the property of the Jews murdered in ‘Aktion Reinhardt.’ In June 1942, three freight cars stocked with baggage taken from Viennese Jews bound for Sobibor were diverted to Trawniki, the same month a small Jewish labour detachment of 20 to 40 women was assigned to sort, clean and repair the clothing. As his SS and police continued to murder the vast majority of Jews in the General Gouvernement, Heinrich Himmler grew increasingly concerned over private companies, exploiting the Jewish labour force and making huge profits, at the expense of the SS. On 9 October 1942, he ordered the transfer of all privately owned factories producing armaments and related goods, along with their Jewish forced workers from ghettos in the General Gouvernement to camps, including Trawniki, where the Jews could be easily guarded. In the late autumn of 1942, SS authorities moved a brush factory and its workers from the Miedzyrzec-

On 8 February 1943, Globocnik signed a contract with Fritz Emil Schultz of F.W.Schultz and Co, which produced mattresses and furs and repaired boots and uniforms. The contract provided that the Schultz fur production plant with its 4,000 Jewish workers and brush-

Initially, the SS encouraged Schultz workers to voluntarily relocate, and on 16 February 1943, transports began to leave Warsaw for Trawniki. Despite threats to shoot those who ignored SS incentives, Schultz could only persuade 448 out of 1,500 workers scheduled for transfer by 14 April 1943 actually to board the trains. Losing patience, the SS decided to liquidate the Warsaw ghetto. At 3.00 a.m. on the morning of 19 April 1943, SS and police units, including a battalion of 350 Wachmanner, sealed off the ghetto, sparking the famous Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Johann Schwarzenbacher saw active service in the Warsaw ghetto uprising along with his SS-

Franz Bartetzko (From the book Letzte Spuren - by Helge Grabitz and Wolfgang Scheffler)

Small detachments of prisoners worked directly for the SS in barracks construction and camp upkeep and two transports of Jewish workers arrived in Trawniki from the Minsk ghetto after its liquidation in September 1943. In the interests of heightened production, Bartetzko initially maintained relatively decent conditions in Trawniki. He reportedly tolerated illicit trade in food and alcohol, permitted Jewish prisoners to form their own musical band and even offered opportunities to play football. After August 1943, however, conditions deteriorated, medical care became non-

For a variety of reasons, including Globocnik’s quarrels with the civilian District Governor in Lublin and Osti’s failure to secure contracts with the Wehrmacht, the SS leadership transferred the Trawniki complex to the jurisdiction of the SS –Business Administration Main Office (WVHA) in September 1943. Trawniki thus became a sub-

Trawniki - Kommandatur 2004 (Chris Webb Archives)

There they were forced to undress, put their clothes in a huge heap, and enter the trench, where they were shot. Those who arrived subsequently were forced to lie on the corpses that had been shot before. When there was no more room in the trench in the training camp, some of the Jews were shot in the sand or in a gravel pit in the labour camp. To overcome the cries of the victims and the noise of the shooting, loudspeakers were installed in the camp and music was heard throughout the entire area. By late afternoon the murder action was completed –all the Jews had been shot and the few Jews who had succeeded in escaping from the shooting site had been caught and shot. A German manager of the Schultz’s enterprises in Trawniki, Kurt Ziemann testified about the events on the morning of 3 November 1943: The labour camp was surrounded. As we found out later, there was an entire SS battalion – young SS men from the Waffen-

After the massacre, the Trawniki SS and police staff imported a small detachment of Jewish workers from Milejow to burn the corpses on massive grills made from railway tracks, then to disperse the ashes and bone fragments into trenches, which they covered with earth. After completing this dreadful work, the Jewish workers were shot and their bodies cremated. For weeks after this massacre, the Trawniki –manner searched the camp grounds for hidden Jews. Those who were found within the first few weeks were shot. Zina Czapnik and her niece, Raja Mileczina , were able to hide away for nearly two months before the Wachmanner discovered them. To Czapnik’s astonishment, both women were permitted to live. They joined a detachment of approximately 40 Jewish women of Austrian and Dutch origin, who had been brought to Trawniki after the massacre to perform domestic tasks inside the camp complex, such as laundry, and cleaning the barracks for the SS staff and the Wachmanner. They also sorted and recycled Jewish clothing and property. In May 1944, the SS transferred this small detachment to the Lublin concentration camp and the Trawniki labour camp was dissolved.

Neither, Willi Franz and Johann Schwarzenbacher, survived the war; Franz went missing on 11 July 1944, while Schwarzenbacher was killed by partisans near Trieste, Italy on 2 June 1944. Franz Bartetzko was also killed in action at the front in January 1945. Karl Streibel, the camp commandant and Bartetzko’s deputy Josef Napierella and four Trawniki company commanders were indicted by a West German court in Hamburg, during 1970. All six defendants were acquitted in 1976, as they had no knowledge or control of the ‘Aktion Erntefest’ massacres of November 1943.

Heinrich Himmler Visit to Trawniki

19 July 1942

All Photographs Courtesy of USHMM

SOURCES:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-

Robert Kuwalek, From Lublin to Belzec –Traces of Jewish Presence in SouthEastern Part of the Lublin region, AD REM Lublin 2006

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor Treblinka,Indiana University Press – Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust ,Collins, London 1986

French L. Maclean, The Camp Men, Schiffer Military History Atglen PA 1999

Helge Grabitz and Wolfgang Scheffler, Letzte Spuren, Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1993

Johann Schwarzenbacher-

Photographs – Yad Vashem, Israel, Chris Webb Archives, USHMM, Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2019