Kielce

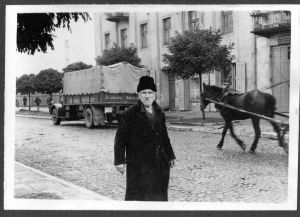

Kielce - Jewish Man - September 1939

Kielce is a city in central Poland on the banks of the River Silnica. During the early 1920’s, about 15,000 Jews lived in Kielce, representing more than one-third of the city’s population. Most earned their living from commerce and from the garment, carpentry and chemical industries. There were also small-scale merchants and numerous peddlers among the city’s Jews. Kielce boasted trade unions for artisans and Jewish residents exercised considerable influence on the labour organisations. Kielce had a credit co-operative and Jewish banks, one of which was supported by the American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). The community also ran several traditional welfare institutions, including a Jewish hospital. Kielce had a Beit Yaakov school for girls as well as fifteen traditional Hadarim, some of which were modernised and included general studies in their curriculum. Agudath Israel operated a Talmud Torah in the city in addition to a higher Yeshiva, and Kielce also had a Yavne school, a secular Jewish school for girls, and co-educational Jewish high schools.

During the interwar years, a variety of Zionist parties were active in the city, as were Agudath Israel, the Bund, and Polish- Communist Jews. The parties ran youth movements and the Zionists also operated pioneer training facilities. The Zionists and Po’alei Agudath Israel offered general education courses in the evenings. Kielce had cultural societies that promoted the study of Hebrew and Yiddish culture, in addition to strong Hasidic communities. The Jewish community had three libraries and a small Jewish theatre; at various times, four Yiddish newspapers were published in Kielce. The city also boasted a number of Jewish sports clubs.

On 11-12 November 1918, after the First World War had just ended, some Poles carried out a pogrom in Kielce, in which they injured 400 Jews and murdered 10. In the 1930’s a number of violent anti-Semitic incidents occurred in the city. In November 1934, three Jews were murdered near Kielce, and in 1937, a pogrom was carried out in the city, during which the homes of fifty Jewish families were burnt down and five Jews lost their lives. In 1938, there were 20,942 Jews living in Kielce, out of a total population of 67,634.

Kielce was occupied by the Germans on 5 September 1939, and immediately after the occupation, the Germans set about plundering Jewish property and abusing Jews in the streets. During mid-September 1939, Jews were abducted for forced labour and a number of Jewish community leaders were arrested. The Germans appropriated Jewish-owned homes on the city’s main streets that were designated as an area reserved for Germans, and forbidden to Jews. However, many of the Jews continued to live in their own homes alongside their Polish neighbours for another year and a half. In early 1939, a Judenrat was established, headed by physician and community leader Moshe Pelc, a member of the city council, who had close ties with Poles and was fluent in German. The Judenrat was required to pay exorbitant ransom payments to the Germans. As increasingly higher numbers of Jews were seized for forced labour, the Judenrat offered the German police a supply of regular workers to work on various infrastructure and military projects, in the city and at a local quarry. To meet the Germans ever growing demands for forced labourers, the Judenrat established a work-brigade that recruited thousands of the poorest Jews, in exchange for a pitiful wage.

On 1 December 1939, the Jews of Kielce were ordered to wear a white armband with a blue Star-of-David and to mark their shops clearly and during the same month the Germans began to systematically confiscate all Jewish –owned factories and businesses in the city. In January 1940, the Germans closed all of the city’s synagogues and issued a prohibition against public prayer, although Jews continued to gather in private homes to pray. By March 1940, the Jewish population of Kielce had grown to 25,400, owing to the influx of Jewish refugees from western Poland and some areas annexed to the Third Reich. On 4 August 1940, another 3,000 Jews arrived in Kielce from Cracow. The Judenrat moved heaven and earth to find housing for the refugees and also established soup kitchens, an old-age home, and a clinic. Moshe Pelc took advantage of the fact that the Jews of Kielce had not been separated from the Polish population, making extensive use of his Polish contacts to implement initiatives that improved the quality of life of Kielce’s Jews, in particular to combat the typhus epidemic that broke out in early 1940. The Judenrat’s welfare activities were supported by the Cracow arm of the Jewish Self-Help (JSS) as well as by the JDC, which supplied Jews with winter clothing. Taxes levied on the city’s Jews also contributed to the organisation. The Judenrat also held a number of courses for nurses in co-operation with TOZ (Society for the Protection of the Health of the Jewish Population in Poland).

With the agreement of the Germans, the Kielce Judenrat set up workshops to manufacture various products. Working conditions in them were reasonable, but the Judenrat managed to employ only a few hundred Jews in the workshops. In July 1940, the Germans began to seize hundreds of workers for labour camps located in the Lublin area. Rumours about harsh conditions in the camps made the Judenrat’s task of recruiting more workers a challenge, leading the Judenrat to appeal to the Germans for help, a step that many Jews thought as collaboration. In the summer of 1940 Moshe Pelc recognised that he was ineffective in his negotiations with the Germans and duly resigned as head of the Judenrat, claiming ill-health. His deputy, Herman Levi, an industrialist and economist, who had excellent ties with the Poles, and a former city council member, took his place and served as the provisional Judenrat chairman. In August 1940, the Judenrat was re-organised and twenty-four delegates were elected from among the various sectors of the Jews of Kielce, including the refugees. Ten departments were set up to tend to the assorted needs of the Jews. In December 1940 Moshe Pelc commenced to run the Jewish hospital and Herman Levi was officially appointed to succeed him, and during his first few months as the head of the Judenrat, he managed to bring about small improvements in the living conditions of the city’s Jews.

On 19 February 1941, four transports arrived in Kielce carrying about 5,000 Jews deported from Vienna, Austria, some of whom had been quite wealthy. Most remained in Kielce for only a short period and were transferred to other locations in the area. About 1,000 of the arrivals from Vienna remained in the city; many found it difficult to adjust to life there, and failed to interact with the local Jewish residents. On 7 March 1941, another 1,000 Jews arrived in the city, from Lodz which had been annexed to the Reich and on the eve of the establishment of the ghetto, approximately 30,000 Jews now lived in Kielce. On 31 March 1941, the German commander of Kielce, Drechsel, issued an order to establish a Jewish residential quarter in the city. The Jews were ordered to move into one of its poorest neighbourhoods by 5 April 1941, and the Polish residents were ordered to vacate. The ghetto was encircled by a high fence that enclosed twenty-six streets and some 600 buildings. The River Silnica divided the area in two. There was a Large Ghetto which included the streets; Nowowarszawska, Orla, Piotrkowska, Pocieszki, and Radomska and a Small Ghetto that included the streets; Bodzentynska, Radomska and St. Wojech Square.

Following the establishment of the ghetto, the Judenrat formed a Jewish Order Service, which numbered 85 members in May 1941 and 120 members in early 1942. Many of the Jewish policemen were refugees from Vienna and Lodz, and Singer who had been deported from Vienna, was the first head of the Jewish Order Service, although he was deported to Auschwitz and his place was taken by Kaltwasser, who in turn was replaced by Bruno Schindler from Lodz during 1942. Just after the ghetto was established a severe typhus epidemic broke out and the Judenrat did all it could to contain the outbreak. The ghetto was hermetically sealed in the first six weeks of its existence, and many of its residents suffered from starvation. Afterwards, Jews with permits were allowed to return to work at their various jobs, whilst Poles were permitted to enter and leave the ghetto. For about six months the food shortages were overcome by trading with the Poles, but this all ended when on 15 October 1941, the Germans sealed off the ghetto to the Poles. This development was a crushing blow to the Jews who had grown dependent on smuggling and the black market for their food. Those Jews caught outside the ghetto without a permit were beaten and some were murdered, including children. The Judenrat strove to alleviate starvation by allocating small plots of land inside the ghetto for residents to grow vegetables.

The establishment of the ghetto had a significant impact on the Jewish workshops, only about half of which managed to remain in business. In the spring of 1941, the Germans sent about 1,000 Jews to construct roads in the Belzec area. The Judenrat continued to be responsible for the supply of workers, but their efforts to help the forced labourers were not particularly successful. In June 1941, the Germans arrested Moshe Pelc together with a number of Jewish and Polish doctors suspected of Communist tendencies and deported them to Auschwitz concentration camp, where Pelc perished. In late July and early August 1941, the Germans arrested Jews from eastern Poland, who had slipped into the ghetto after the German invasion of the Soviet Union and murdered them in the Kielce prison. In the winter of 1941/42, the living conditions of the ghetto’s Jews worsened considerably, due to hunger and cold, and many perished. The Judenrat assisted the needy, organising the collection of clothing and food, and in February 1942, holding two benefit concerts, the proceeds of which went towards helping the community’s poor. The ghetto had a hospital, an old-age home, an orphanage, and a number of public soup kitchens. A dormitory for needy children was established, offering more than 200 children food and vocational training. In March 1942, the Germans ordered that the Judenrat establish a large workshop in the ghetto for professionals Despite these efforts, the unemployment levels was very high, particularly among women. A month later in April 1942, approximately 1,900 Jews were assigned to forced labour in the HASAG ammunition factory in Skarzsko- Kamienna, which is some 22 miles from Kielce.

Kielce - Jewish Temple 2004

On 27 -28 April 1942, the Germans launched a murder operation in the ghetto, during which Jews who were suspected of Communist ties were arrested, along with former officers in the Polish army and a number of doctors. Some of those seized were murdered, whilst others were deported. During 20 to 24 August 1942 the Germans conducted a large scale ‘Aktion’ in Kielce, which saw the deportation of 21,000 Jews to the Treblinka death camp. To facilitate this major deportation operation, the German forces in Kielce were reinforced by units of the SS security police, under the command of Gottfried Feucht and by Ukrainian –SS. On 19 August 1942, before dawn, the Germans, led by the chief of the local Schutzpolizei, Hans Gaier, and the local Gestapo head, Ernst Karl Thomas, rounded up the Judenrat, and Jewish Order Service members. The Germans assured their captives that in exchange for assisting with the deportation to the east, they and their families would be spared the agony of deportation.

On 20 August 1942, an extremely brutal ‘Aktion’ was launched by the Germans and their auxiliary SS-Ukrainian forces. The members of the Jewish Order Service were forced to evacuate the Jews from their homes. The Jews rounded up had their work permits inspected by Gaier and Thomas. These two men carried out selections and executions of those Jews rounded up. Young people selected for work, returned to the ghetto, while the rest were deported to the Treblinka death camp. After the deportations were ended on 24 August 1942, the German security police and the Jewish Order Service policemen searched the ghetto buildings, and anyone found hiding was shot on the spot. On 24 August 1942, Ernst Thomas ordered the execution of Bruno Schindler, the head of the Jewish Order Service, and had his wife deported to the Treblinka death camp. In addition to the 21,000 Jews, the majority of whom perished in the gas chambers, another 1,500 to 2,000 Jews, including children, pregnant women, the ill and the elderly, were murdered in the ghetto during the deportation ‘Aktion’.

On 28 August 1942, approximately 1,500 Jews who survived the mass deportation were concentrated in the Jewish quarter, known as the ‘Small Ghetto,’ including about sixty children, all of whom were the children of the members of the Jewish Order Service. The ghetto was closed and had a single gate. Gustav Speigel a Jew from Vienna was appointed to head the Jewish Order Service, and he became the most powerful figure in the ghetto and fully collaborated with the Germans. The head of the Judenrat Herman Levi, who remained in the small ghetto with his family, no longer had any authority. In late 1942, a small Underground cell was established in the small ghetto under the leadership of Daniel Wiener and Levkovitz. The members of the Underground managed to establish contact with the Poles outside the ghetto. They managed to smuggle in a machine gun and a few handguns, but no major battles were fought with the Germans.

In January 1943, the Germans searched the ghetto with Spiegel’s assistance and deported about 150 Jews to a labour camp in Starachowice. In March 1943, the Germans murdered Herman Levi and his family, along with another forty residents of the ghetto, primarily physicians and their families. On 14 May 1943, about 120 Jews from the small ghetto were transferred to the Skarzsko- Kamienna labour camp. The small ghetto was liquidated on 29 May 1943, when Gaier carried out a selection among its residents. Approximately fifty children were separated by force from their parents and locked up in a nearby building; most were murdered three days later, with the exception of three who managed to escape. Among the adults, about 900 Jews were transferred to various labour camps, mostly to Plonki, and approximately 500 people were rounded up in labour camps established near the Ludwikow steel factory and the Henrykow wood-processing factory. These Jews lived for fourteen months under reasonable working and living conditions. The Germans appointed Viennese Jews Otto Glattstein and Gustav Spiegel to supervise the two camps. The Germans from time to time terrorised the workers in Ludwikow and Henrykow, and executed people suspected of planning to escape. On 1 August 1944, the Germans deported the two labour camp workers to Auschwitz.

Sources:

The Yad Vashem Encylopiedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust Volume 1, Yad Vashem, 2009.

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Photographs - Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018