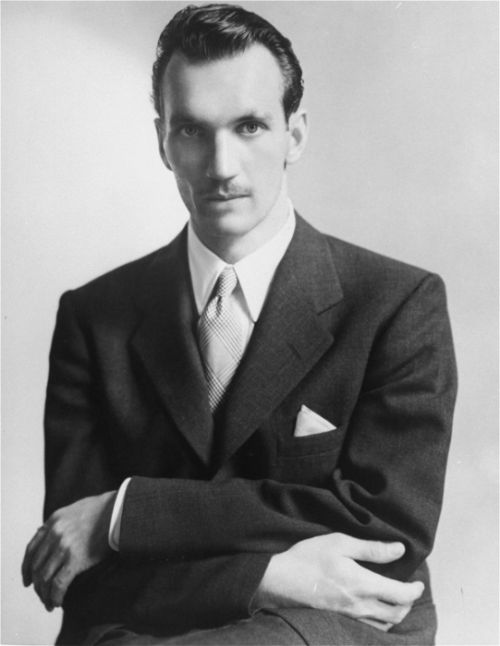

Jan Karski

Jan Karski Statue - Krakow 2016

Jan Karski was born on April 24, 1914, the youngest of eight children, born in a tenement house at Kilinskiego Street in Lodz, with his real name of Jan Kozielewski. Following the completion of his secondary schooling he went to Lvov in 1931, to study there. He was awarded with a Doctor of Law and Diplomacy title, and he later worked in the Diplomatic Corps, in pre-war Poland and he secured coveted overseas postings in London and Paris.

Just prior to the Nazi invasion of Poland, Jan Kozielewski enlisted in the Polish army and served as a cavalry officer, when first the Germans and then the Soviets invaded Poland during September 1939. He was captured by the Soviet forces and incarcerated in a detention camp. He escaped from the camp and joined the Polish Underground, whilst most of his fellow captives were later executed by the Soviets.

Now using the non de plume Jan Karski he became a skilled courier for the Polish Underground, working with the Allied forces in the West, it was during this period whilst employed on Underground work he was arrested by the Gestapo in Preshov, Slovakia in 1940, and he was brutally tortured. Fearing that he might reveal secrets and betray his fellow Underground colleagues he slashed his own wrists, and was put into a hospital from where he was able to escape, with the help of the Underground.

In the third week of August 1942, during the mass deportation of the Jews of Warsaw to the Treblinka extermination camp, Jan Karski entered the Warsaw Ghetto with two Jewish leaders, Leon Feiner and Adolf Berman. They both urged Jan Karski to inform the Allied leaders about the mass extermination of Polish Jewry, and to seek from the Allies a commitment that preventing the extermination of the Jews should be publically declared as an official goal of the Allies. Jan Karski was invited by the two Jewish leaders to visit the Warsaw Ghetto, and what follows is Karski's account of that visit:

There was a tunnel dug under that building the back wall of which formed part of the ghetto wall and with its facade looking onto the Aryan side; we negotiated it with no trouble. And suddenly we found ourselves in a completely different world. The Bund leader who until recently had looked like a Polish nobleman suddenly stooped like a ghetto Jew, as if he had been there for ever. This was his nature, his world. We were passing the streets, him on my left, and we did not talk much. There were naked, corpses lying in the streets. I asked: "Why are they lying there?" He answered: "That's a problem. When a Jew dies and the family want to bury him, they have to pay. They have no money and so they throw their dead out into the street. Every bit of rag has its value and that's why they strip them of their clothes. When the naked bodies are in the street, they become the business of the Jewish Council."

Women breast-feeding infants in full view of everyone. Only they have no breasts... their chests are completely flat there. Infants with eyes of madmen are looking at us. This was not this world, this was not mankind.

The streets are crowded, filled, as if everybody lived outdoors. They are displaying their poor riches, everyone is trying to sell whatever he or she has: three onions, two onions,' a couple of tacks. Everybody is selling something, everybody is begging. Hunger. Terrible children. Children running by themselves, children sitting by their mothers. This was not mankind, it was a kind of hell.

Through this part of the central ghetto German officers used to pass. Off duty German officers made a shortcut walking across the ghetto. So uniformed Germans were walking. Dead silence fell. Everybody was watching them passing, frozen with fear, with no movement, not a word. The Germans were contemptuous, you could sense that they did not regard those dirty subhumans as human beings. Suddenly panic broke out. Jews were fleeing from the streets we were walking along. We were rushing towards one of the houses, my companion murmured, "The door -- open the door' -- someone opened it and we entered. We were hurrying to the windows facing the street. Then we were going back to the door and the woman standing by it. He said, "Don't be afraid, we're Jews." He pushed me towards the window, "Look." Two boys with nice faces and wearing Hitlerjugend uniforms were passing. They were talking. With each step they made, the Jews scattered, vanished. And they continued talking. Suddenly one of them reached into his pocket and without a moment's hesitation fired a shot. The sound of broken glass, the howling of a man. The other one congratulated him and they went away.

I was standing stock-still. And then the Jewish woman who must have realized that I was not Jewish embraced me, "Go away, it's not for you. go away."

We left the house and we left the ghetto. He told me, "You didn't see all. Do you want to come back? I shall come with you, I want you to see everything."

We returned the following day through the same building. This time the shock was not so great and I noticed other things. Stench, dirt. Suffocating stench. Dirty streets. The atmosphere of excitement, tension, frenzy. This was Muranowski Square. In one corner children were playing with rags. They were throwing rags at each other. He said. "Look, children are playing. Life goes on." I answered, "They are not playing, they are only pretending." Nearby there were several sickly trees. We were walking farther talking to no one. We walked like that for about an hour. Occasionally he stopped me, "Look at this Jew," a man standing motionless. I asked, "Is he still alive?" -- "Oh yes, he's alive all right," he replied. "Pan Witold, please remember, he is in the process of dying. He is just dying. Look at him, please, and tell them over there. You saw, him, please remember." We went on. Horror! From time to time he whispered, "You must remember this, and this, and that. And this woman." Often I asked him, "What is happening to these people?" He answered, "They're dying. Don't forget. Please remember."

This went on for about half an hour, and then we turned back. I could not stand it any longer. "Please take me out." I did not see him any more. I was ill. Even now I do not want any more. I can understand what you are doing and therefore I am here. But I had not gone back to my memories. I couldn't any longer.

I conveyed my report and I told them what I had seen. It had not been the world that I had seen. It had not been mankind. I wasn't there, I didn't belong there. I had never before seen anything like that. And no one had described such reality. Nor shown it in a drama or a film.

This was not the world. I was told they were human beings but they did not recall human beings any longer. . |

We left, he embraced me. "Good luck." I answered, "Good luck." I never saw him again.

Izbica 2002

Jan Karski was invited by Leon Feiner and Adolf Berman to further witness the brutal treatment of the Jews by the Germans and arranged in September 1942, for Karski to visit the Izbica Transit ghetto, a small village, 41 miles from Lublin. Karski accompanied by his guide travelled by train from Warsaw, to Izbica, via Lublin. Karski's in his own words described the visit. In the grocery store Karski changed from his civilian clothes into the uniform of an Estonian guard and they set off:

'As we approached to within a few hundred yards of the camp, the shouts, cries and shots, cut off further conversation. I noticed, or thought I noticed, an unpleasant stench that seem to have come from decomposing bodies mixed with horse manure. This may have been an illusion. The Estonian was, in any case, completely impervious to it. He even began to hum some sort of folk tune to himself. We passed through a small grove of decrepit -looking trees and emerged directly in front of the loud, sobbing, reeking, camp of death.

It was on a large, flat plain and occupied about a square mile. It was surrounded on all sides by a formidable barbed-wire fence, nearly two yards in height and in good repair. Inside the fence, at intervals of about fifteen yards, guards were standing holding rifles with fixed bayonets ready for use. Around the outside of the fence, militia men circulated on constant patrol. The camp itself contained a few small sheds or barracks. The rest of the area was completely covered by a dense, pulsating, throbbing, noisy human mass. Starved, stinking, gesticulating, insane human beings in constant, agitated motion. Through them, forcing paths, if necessary, with their rifle butts, walked the German police and the militia men. They walked in silence, their faces bored and indifferent. They looked like shepherds bringing a flock to the market, or pig-dealers among their pigs. They had the tired, vaguely disgusted appearance of men doing a routine, tedious job.

Into the fence, a few passages had been cut, and gates made of poles tied together with barbed-wire, swung back, allowing entrance. Each gate was guarded by two men, who slouched about carelessly. We stopped for a moment to collect ourselves. To my left I noticed the railroad tracks which passed about a hundred yards from the camp. From the camp to the track a sort of raised passage had been built from old boards. On the track a dusty freight train waited, motionless. The Estonian followed my gaze with the interest of a person seeing what kind of impression his home made on a visitor. He proceeded eagerly to enlighten me. 'That's the train they'll load them on. You'll see it all.'

We came to a gate. Two German NCO's were standing there talking. I could hear snatches of their conversation. They seemed to be talking about a night they had spent in a nearby town. I hung back a bit. The Estonian seemed to think I was losing my nerve. 'Go ahead,' he whispered impatiently in my ear. 'Don't be afraid. They wont even inspect your papers. They don't care about the likes of you.' We walked up to the gate and saluted the non-coms vigorously. They returned the salute indifferently and we passed through, entering the camp and mingled unnoticed with the crowd. 'Follow me,' he said quite loudly, 'I'll take you to a good spot.'

We passed an old Jew, a man of about sixty, sitting on the ground without a stich of clothing on him. I was not sure whether his clothes had been torn off or whether he, himself had thrown them away in a fit of madness. Silent, motionless, he sat on the ground, no one paying him the slightest attention. Not a muscle or fibre in his whole body moved. He might have been dead or petrified, except for his preternaturally animated eyes, which blinked rapidly and incessantly. Not far from him a small child, clad in a few rags, was lying on the ground. He was all alone and crouched quivering on the ground, staring up with the large frightened eyes of a rabbit. No one paid any attention to him either. The Jewish mass vibrated, trembled and moved to and fro, as if united in a single insane, rhythmic trance. They waved their hands, shouted, quarrelled, cursed, and spat at each other. Hunger, thirst, fear, and exhaustion had driven them all insane. I had been told that they were usually left in the camp for three or four days, without a drop of water or food. They were all former inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto. When they had been rounded up they were given permission to take about ten pounds of baggage. Most of them took food, clothes, bedding, and, if they had any, money and jewellery.

On the train, the Germans who accompanied them, stripped them of everything that had the slightest value, even snatching away any article of clothing to which they took a fancy. They were left a few rags for apparel, bedding and a few scraps of food. Those who left the train without any food, starved continuously from the moment they set foot in the camp.

There was no organisation, or order of any kind. None of them could possibly help or share with each other and they soon lost any self-control or any sense whatsoever except the barest instinct of self-preservation. They had become at this stage, completely de-humanised. It was moreover, typical autumn weather, cold, raw, and rainy. The sheds could not accommodate more than two or three thousand people and every 'batch' included more than five thousand. This meant there were always two to three thousand men, women, and children scattered about in the open, suffering exposure as well as everything else. The chaos, the squalor, the hideousness of it all, was simply indescribable. There was a suffocating stench of sweat, filth, decay, damp straw and excrement.

To get to my post, we had to squeeze our way through this mob. It was a ghastly ordeal. I had to push foot by foot through the crowd and step over the limbs of those who were lying prone. It was like forcing my way through a mass of sheer death and decomposition, made even more horrible by its agonising pulsations. My companion had the skill of long practice, evading the bodies on the ground and winding his way through the mass with the ease of a contortionist. Distracted and clumsy, I would brush against people or step on a figure that reacted like an animal quickly, often with a moan or a yelp. Each time this occurred I would be seized by a fit of nausea and come to a stop. But my guide kept urging and hustling me along. In this way we crossed the entire camp and finally stopped about twenty yards from the gate which opened on the passage leading to the train. It was a comparatively un-crowded spot. I felt immeasurably relieved at having finished my stumbling, sweating journey.

The guide was standing at my side, saying something, giving me advice. I hardly heard him, my thoughts were elsewhere. He tapped me on the shoulder. I turned towards him mechanically, seeing him with difficulty. He raised his voice, 'Look here. You are going to stay here. I'll walk on a little further. You know what you are supposed to do. Remember to keep away from Estonians. Don't forget if there's any trouble, you don't know me and I don't know you.' I nodded vaguely at him. He shook his head and walked off. I remained there perhaps half an hour, watching this spectacle of human misery. At each moment I felt the impulse to run and flee. I had to force myself to remain indifferent, practice stratagems on myself to convince myself that I was not one of the condemned, throbbing multitude, forcing myself to relax, as my body seemed to tie itself into knots, or turning away at intervals to gaze into the distance at a line of trees near the horizon.

I had to remain on the alert too, for an Estonian uniform, ducking toward the crowd or behind a nearby shed, every time one approached me. The crowd continued to writhe in agony, the guards circulated about, bored and indifferent, occasionally distracting themselves by firing a shot or dealing out a blow. Finally, I noticed a change in the motion of the guards. They walked less and they all seemed to be glancing in the same direction - at the passage to the track which was quite close to me. I turned toward it myself.

Two German policemen came to the gate with a tall bulky SS man. He barked out an order and they began to open the gate with some difficulty. It was very heavy. He shouted at them impatiently. They worked at it frantically and finally whipped it open. They dashed down the passage as though they were afraid the SS man might come after them, and took up their positions where the passage ended. The whole system had been worked out with crude effectiveness. The outlet of the passage was blocked off by two cars of the freight train, so that any attempt on the part of one of the Jews to break out of the mob, or to escape, if they had so much presence of mind left, would have been completely impossible. Moreover, it facilitated the job of loading them onto the train.

The SS man turned to the crowd, planted himself with his feet wide apart and his hands on his hips and loosed a roar that must have actually hurt his ribs. It could be heard far above the hellish babble that came from the crowd, 'Ruhe, Ruhe!' Quet, Quiet! All Jews will board this train, to be taken to a place where work awaits them. Keep order. Do not push. Anyone who attempts to resist or create a panic will be shot.' He stopped speaking and looked challengingly at the helpless mob that hardly seemed to know what was happening.

Suddenly accompanying the movement with a loud hearty life, he yanked out his gun and fired three random shots into the crowd. A single stricken groan answered him. He replaced the gun in his holster, smiled and set himself for another roar, 'Alle Juden raus - raus!' For a moment the crowd was silent. Those nearest the SS man recoiled from the shots and tried to dodge, panic-stricken, toward the rear. But this was resisted by the mob, as a volley of shots from the rear sent the whole mass surging forward madly, screaming in pain and fear. The shots continued without let-up from the rear and now from the sides too, narrowing the mob down and driving it in a savage scramble onto the passageway.

In utter panic, groaning in despair and agony, they rushed down the passageway, trampling it so furiously that it threatened to fall apart. Here new shots were heard. The two policemen at the entrance to the train were now firing into the oncoming throng corralled in the passageway, in order to slow them down and prevent them from demolishing the flimsy structure. The SS man now added his roar to the deafening bedlam, 'Ordnung, Ordnung,' he bellowed like a madman. 'Order, Order!' the two policemen echoed him hoarsely, firing straight into the faces of the Jews running to the trains. Impelled and controlled by this ring of fire, they filled the two cars quickly.

And now came the most, the most horrible episode of them all. The Bund leader had warned me that if I lived to a hundred I would never forget some of the things I saw. He did not exaggerate. The military rule stipulates that a freight car may carry eight horses or forty soldiers. Without any baggage at all, a maximum of a hundred passengers standing close together and pressing against each other could be crowded into a car. The Germans had simply issued orders to the effect that 120 to 130 Jews had to enter each car. These orders were now being carried out. Alternately swinging and firing with their rifles, the policemen were forcing still more people into the two cars, which were already over-full.

The shots continued to ring out in the rear and the driven mob surged forward, exerting an irresistible pressure against those nearest to the train. These unfortunates crazed by what they had been through, scourged by the policemen, and shoved forward by the milling mob, then began to climb on the heads and shoulders of those on the trains. These were helpless since they had the weight of the entire advancing throng against them and responded only with howls of anguish to those who, clutching at their hair and clothes for support, trampling on necks, faces and shoulders, breaking bones, and shouting with insensate fury, attempted to clamber over them. More than another score of human beings, men, women and children gained admittance in this fashion. Then the policemen slammed the doors across the hastily withdrawn limbs that still protruded and pushed the iron bars in place.

The two cars were now crammed to bursting with tightly packed human flesh, completely hermetically filled. All this while the entire camp had reverberated with a tremendous volume of sound in which the hideous groans and screams mingled weirdly with shots, curses, and bellowed commands. Nor was this all, I know that many people will not believe me, will not be able to believe me, will think I exaggerate or invent. But I saw it and it is not exaggerated or invented. I have no other proofs, no photographs. All I can say is that I saw it and that is the truth.

The floors of the car had been covered with a thick white powder. It was quicklime. Quicklime is simply un-slaked lime, or calcium oxide that has been dehydrated. Anyone who has seen cement being mixed knows what occurs when water is poured on lime. The mixture bubbles and steams as the powder combines with the water, generating a large amount of heat. Here the lime served a double purpose in the Nazi economy of brutality. The moist flesh coming in contact with the lime is rapidly dehydrated and burned. The occupants of the cars would be literally burned to death before long, the flesh eaten from the bones. Thus the Jews would die in agony, fulfilling the promise Himmler had issued in accord with the 'will of the Fuhrer' in Warsaw in 1942. Secondly the lime would prevent decomposing bodies from spreading disease. It was efficient and inexpensive - a perfectly chosen agent for their purposes.

It took three hours to fill up the entire train by repetitions of this procedure. It was twilight when the forty -six (I counted them) cars were packed. From one end to the other, the train, with its quivering cargo of flesh, seemed to throb, vibrate, rock and jump as if bewitched. There would be a strangely momentary lull and then, again, the train would begin to moan and sob, wail and howl. Inside the camp a few score dead bodies remained and a few in the final throes of death. German policemen walked around at leisure with smoking guns, pumping bullets into anything, that by a moan or motion betrayed an excess of vitality. Soon not a single one was left alive.

In the now quiet camp the only sounds were the inhuman screams that were echoes from the moving train. Then these too ceased. All that was now left was the stench of excrement and rotting straw and a queer, sickening acidulous odour which I thought, may have come from the quantities of blood that had been shed and with which the ground was stained. As I listened to the dwindling outcries from the train, I thought of the destination toward which it was speeding. My informants had minutely described the entire journey. The train would travel about eighty miles and finally come to a halt in an empty barren field. Then nothing at all would happen. The train would stand stock-still, patiently waiting while death penetrated into every corner of its interior. This would take from two to four days.

When quicklime, asphyxiation and injuries had silenced every outcry, a group of men would appear. They would be young, strong Jews, assigned to the task of cleaning out these cars, until their own turn to be in them should arrive. Under a strong guard they would unseal the cars and expel the heaps of decomposing bodies. The mounds of flesh that they pilled up would then be burned and the remnants buried in a single huge hole. The cleaning, burning and burial would consume one or two full days. The entire process of disposal would take then from three to six days. During this period the camp would have recruited new victims. The train would return and the whole cycle would be repeated from the beginning.

I was still standing near the gate, gazing after the no longer visible train, when I felt a rough hand on my shoulder. The Estonian was back again. He was frantically trying to rouse my attention and to keep his voice lowered at the same time, 'Wake up, wake up,' he was scolding me hoarsely, 'Don't stand there with your mouth open. Come on hurry, or we'll both be caught. Follow me and be quick about it.' I followed him at a distance, feeling completely be-numbed.

Returning to Warsaw, Jan Karski was given a microfilm of hundreds of documents and he made his way to Berlin, onto Vichy France, onto London, via Spain and Gibraltar. In February 1943, Jan Karski met with the British Governments Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. Later Karski recalled what Anthony Eden had said, stating, 'that Great Britain had already done enough by accepting 100,000 refugees.' Whilst he was in London, Karski also met with Szmuel Zygleboym, who represented the Jewish Socialist Bund in the National Council of the Polish Government in exile, to inform him of what he had witnessed in Poland, and to make him aware of the desperate need for urgent action, and what the two Jewish leaders in the Warsaw ghetto had told him. Szmuel Zygleboym said he would do all he could to help them, but a few months later on the 12 May 1943, just after the Germans crushed the Jewish uprising in the Warsaw ghetto, Zygleboym committed suicide.

In July 1943, Jan Karski, travelled to the United States of America, where he met President Roosevelt. Whilst Jan Karski felt he failed to convince President Roosevelt of the plight of the Jews, this was in fact not so. The President changed American policy by establishing the War Refugee Board, to help settle surviving Jews in America. Jan Karski wanted to return to Poland to continue his work for the Polish Underground, but he was ordered to remain in the USA, as the Germans now knew his identity. During his time in America, he gave interviews and wrote articles. He also wrote a book, 'Story of a Secret State,' which was published at the end of 1944.

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, Jan Karski decided not to return to Poland, as it was now under the control of the Soviets, and he abhorred Communism. At the age of 39, he enrolled at the School of Foreign Services in Georgetown and he committed himself to a life of education, teaching at Georgetown until his retirement in 1984.

In 1965, he married Pola Nirenska, a dancer and choreographer, who had been born in Poland, with the name Pola Nirensztain. She was the daughter of an observant Jewish father, and all her relatives perished in the Holocaust, but she was in London, so escaped the Nazi persecution. She moved to America and became a celebrated name in Washington, teaching, choreographing and leading her own company. Her last dance piece presented in Washington during 1990, was inspired by Holocaust victims, she had known, and was called, 'In Memory of Those I Loved ... Who are No More.'

In 1992, she committed suicide, by jumping from their apartment's balcony, and Jan Karski died on the 15th July 2000, aged eighty-six, from heart and kidney ailments at Georgetown University Hospital.

Jan Karski, Private Archive

Sources:

New York Times

Material Towards a Documentary History of the Fall of Eastern Europe, Jan Karski

Shoah – An Oral History of the Holocaust – Claude Lanzmann – published by Pantheon Books New York 1985

Phtographs: Private Archive, Chris Webb Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2017