Ravensbruck

Ravensbrück - Prisoners at work during 1939 (Bundesarchiv)

During its almost six years of existence from May 1939, until it was liberated by the Red Army on April 30th 1945, approximately 123,000 women from over 40 nationalities were prisoners at Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. Next to the women's section at Auschwitz II- Birkenau,Ravensbrück was the largest women's camp, and between 25,000 to 26,000 female prisoners died there. Over the course of its existence the camp evolved into a complex of facilities that included a small-scale camp for men, nearby industrial facilities and more than 30 sub-camps.

Johanna Langefeld, the first head guard at Ravensbrück recalled her arrival at the Concentration Camp in May 1939:

Johanna Langefeld had come with a small advance party of guards and prisoners to bring equipment and look around the new Concentration Camp for Women, which was due to open on May 15, 1939. Langefeld stepped through the iron gates and strode around the sandy Appellplatz - the camp square. The size of a football pitch .... loudspeakers hung on poles above her head.

Ravensbrück had no watchtowers along the walls, and no gun emplacements. But an electrified fence was fixed to the interior of the perimeter wall and placards along the fence showed a skull and crossbones warning of high voltage. Hulking grey barrack blocks dominated the compound. The wooden barracks were arranged in a grid, were single-storey with small windows; they sat squat around the camp square. Two lines of identical blocks were laid out each side of the Lagerstrasse, the main street of the camp.

Langefeld inspected the blocks one by one. Immediately inside the gate, the first block on the left was the SS canteen, fitted out with freshly scrubbed chairs and tables. Also to the left of the Appellplatz was the camp Revier, a German military term meaning sick-bay or infirmary. Across the square she entered the bath-house, fitted with dozens of showerheads. Next to the bath-house, under the same roof, was the camp kitchen which glistened with huge steel pots and kettles. The next building was the prisoners' clothes store, or the so-called 'Effektenkammer,' and then came the Wascherai, the camp laundry, with its six centrifugal washing machines. Ravensbrück had no bakery ovens of its own, bread was brought daily from Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, which was located some 50 miles to the south.

Stepping inside one of the accommodation barracks, Langefeld looked around .... more than 150 women were to sleep in each block. The blocks interiors were set out in an identical fashion, with two large sleeping rooms -A and B - on either side of a washing area, with a row of 12 basins and 12 lavatories, as well as a communal day room, where the women would eat. The sleeping areas were filled with scores of three-tiered bunks, made of wooden planks. Every prisoner had a mattress filled with wood shavings and a pillow, as well as a sheet and a blue and white check blanket, folded at the foot of the bed.

Ravensbrück 's first commandant was SS-

The guards in the Women's Camp were exclusively female and after early 1942, the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp served as the central training camp for female SS guards at other camps, such as Auschwitz, Lublin and other sub-camps. Suhren later testified that whilst he was commandant, approximately 3,500 female SS guards and 950 members of the Waffen-SS served in Ravensbrück and its sub-camps.

Ravensbrück became operational on 15th May 1939, with the arrival of approximately 1,000 female prisoners from the Women's Camp at Lichtenburg. Members of the Jehovah's Witnesses faith represented the majority of the inmates to the end of 1939. Subsequently, the fastest-growing group of prisoners, the so-called 'asocials.' It was only from the late summer of 1941, that 'political' prisoners outnumbered the 'asocials, ' as increasing numbers of women arrived from occupied countries. The number of Jewish women prisoners shrank considerably due to the murder of 800 inmates as a result of the 14f13 murder project in the spring of 1942, and also because 522 Jewish women were deported to Auschwitz Concentration Camp on 6th October 1942. Only in the second half of 1944, did large numbers of Jewish women prisoners arrive at Ravensbrück.

During 1940, the construction of the so-called Industrial Park began; the constantly growing compound housed the SS-owned Gesellschaft fur Textil und Lederverwertung (Texled), a textile company. By September 1942, approximately 60 per cent of all the female prisoners - between 4,000 and 5,000 were working for Texled. Female prisoners also worked in an SS agricultural enterprise called the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt fur Ernhahrung und Verpflegungh GmbH (DVA). They were also hired out to private agricultural enterprises in the vicinity.

From the middle of 1942, onwards, the prisoners also had to work in the armaments industry. From August 1942, female prisoners worked in the production plants of the electronics company Siemens und Halske (S & H), which was located nearby. In December 1944, when approximately 2,200 prisoners were already working in its 20 workshops, additional barracks were built next to the workshops; this was the so-called Siemens camp.

Starting in 1943, a significant change took place with the establishment of sub-camps near armament factories; this made Ravensbrück into a main camp and transit station. Originally, almost all the women's sub-camps in Germany were under the supervision of Ravensbrück. This changed with the re-structuring of the sub-camps system in the autumn of 1944, when half of the sub-camps for female prisoners were assigned to the main concentration camps nearest to them, mainly Buchenwald, Flossenburg, and Sachsenhausen, but Ravensbrück retained some of its nearby sub-camps.

With the increasing number of prisoners after 1943, the conditions in the women's camp deteriorated. From 1944, the number of prisoners in many of the barracks were four-times the number originally intended. When the barracks capacity was finally exceeded a tent was erected to accommodate the many new arrivals during the late summer and autumn of 1944. There were no blankets for the 3,000 women who occupied the tent, and only a thin layer of straw covered the floor, so the death rate was higher than average. Meanwhile the quantity and the quality of the food fell steadily, adding to the mounting death toll.

The infirmary buildings at Ravensbrück increasingly developed into 'dying zones' since many of the women who suffered from typhus, diphtheria and other diseases died there without receiving even minimal medical treatment. Apart from this the infirmary became a centre for pseudo-medical experiments between 1st August 1942, and 16th August 1943, SS physicians under the leadership of Professor Dr. Karl Gebhardt, carried out experiments on 74 Polish prisoners and 12 prisoners of other nationalities. These experiments included the removal of bones, muscles and nerves, as well as operations that were intended to cause infections, such as gangrene, in order to disprove the possible effectiveness of sulphonamide treatment. In the camp vernacular, the women who had been subjected to these operations were called 'guinea pigs.' Five of the Polish women all 12 of the other nationalities died immediately following the operations, while 6 more were shot a short time later, with their surgical wounds still not healed. Additionally, in early 1945, 120 to 140 Sinti and Roma women and girls - the youngest aged just eight - were subjected to sterilisation experiments, as a result of which, many died.

Between 6th May 1944, and 11th March 1945, 65 Russian women were executed in Ravensbrück on suspicion of sabotage. In addition more than 160 Polish women and several British and French SOE and Resistance members were shot. They had been sent to Ravensbrück after having been sentenced to death by special courts (Sondergerichte).

The men's camp which existed since April 1941, remained under the authority of the women's camp commandant. It served mainly to supply craftsmen and helpers to work on the constantly expanding camp complex. Up to the end of 1944, the men's camp did not accept new prisoners but, with a few exceptions, only those who were transferred from other camps to replace the sick and dead. The number of prisoners remained relatively constant until the end of 1944, between 1,500 and 2,000. The sick were sent to Dachau Concentration Camp at first, then after 1944, to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp; the majority died within days or weeks of arrival, or, in the case of Dachau, were selected for liquidation.

Within Ravensbrück itself there were some targeted extermination programmes, the first of which was the already mentioned 14f13, under which the Germans extended their 'euthanasia' programme to the concentration camps. Under this programme, 1,600 female prisoners and 300 male prisoners of Ravensbrück - half of them Jewish - were killed in the spring of 1942, most probably in the T4 sanatorium at Bernburg. After the completion of these killings , 'undesirable' female prisoners were killed with injections of phenol and morphine. Others were transported out of the camp to the T4 Institute at Hartheim, near Linz, or to concentration camps such as Auschwitz or Lublin. Between 1942, and the end of 1944, approximately 60 of these so-called 'black transports' left Ravensbrück with between 60 and 1,000 prisoners each.

In January 1945, the camp administration began to make preparations for mass killings to be conducted on-site. For this purpose, they partially cleared out the so-called youth protection camp in Uckermark, approximately 1 mile from Ravensbrück. This site, where in January 1945, the older, weaker and sick prisoners were taken from the main camp, quickly developed into a 'death zone' because conditions there were even worse than the main camp. The women were insufficiently clothed, were fed only half their previous rations and received neither blankets nor medical attention. During the roll-calls alone, which lasted five to six hours, 50 prisoners died daily during the cold winter months, of hunger, exposure, exhaustion and the prevailing epidemics. A large number were killed by Luminal - a barbiturate, called 'white powder' by the prisoners - or by being given poisonous injections, or by being selected for mass shootings or death in the gas-chamber. Up to mid-April 1945, over 8,000 women had been transferred to the Uckermark camp, of whom only between 1,300 and 1,500 returned to the main camp.

At the various Ravensbrück trials none of the former SS camp guards denied the existence of a gas chamber, which had been installed in early 1945. This was a wooden structure, in the immediate vicinity of the crematorium, which had served as a storage facility before it was transformed into a temporary gas chamber. Between 150 and 180 people could be killed there at once. The gassing, which began in late January or early February, was most probably stopped only one week before the liberation of the camp. Altogether 5,000 to 6,000 prisoners died there. A second more advanced gas chamber was supposed to be built at the end of March 1945, on the other side of the camp fence and behind the infirmary, but it appears it was never used. A number of ex-prisoners claim that a gas-van was also used, but this cannot be proven.

In early 1945, Ravensbrück held the greatest number of prisoners in its history, which was confirmed by a letter drafted to the SS-WVHA dated 15th January 1945, stating the presence of 46,070 female prisoners and 7,848 male prisoners in Ravensbrück and its sub-camps. The simply horrific overcrowding in the barracks, as well as the increasingly catastrophic hygienic conditions led to an outbreak of a typhus epidemic in the women's camp. The greatest threats that the female prisoners faced, however, were the constant selections for the weaker, elderly and sick prisoners for death at Uckermark. In addition the camp administration relieved itself of approximately 5,600 female prisoners in March 1945, by sending them on transports to Mauthausen and Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camps. The following month in April 1945, the Swedish Red Cross evacuated approximately 7,500 female prisoners, most of them from Scandinavia, the Benelux, France and Poland.

Of the male prisoners, 2,100 had been evacuated in early March 1945, to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, but in mid-April transports with more than 6,000 male prisoners from the Mittlebau main camp Dora and the Neuengamme sub-camp of Watenstedt arrived. These new arrivals were in a bad shape to begin with, and received no care, so many of them did not survive. On 24th April and 26th April 1945, the male prisoners were forced- marched in several columns in a north-westerly direction. On 27th April and 28th, approximately 20,000 female prisoners were made to march in the same direction. Approximately 2,000 sick men, women and children were left behind. On 29th April 1945, the last of the SS men left the camp, and on the following day 30th April 1945, advance units of the Red Army arrived. On 1st May 1945, the Russian forces arrived and liberated the last of the Ravensbrück prisoners.

Odette Sansom

Odette Sansom was born on April 28, 1912, to Gaston and Yvonne Brailly, in Amiens, France. She married an Englishmen Roy Sansom, whom she met in Boulogne. They moved to London and they raised a family of three girls, Francoise, Lili and Marianne. Odette was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and trained at the Beaulieu estate in Hampshire.

Odette was sent into France where she made contact on the Rivera with 'Raoul' who was SOE agent Peter Churchill, who was based in Cannes. Odette and Peter Churchill were arrested on April 16, 1943, in St.Joritz, by Hugo Bleicher, the German Millitary Intelligence (Abwehr) and Italian troops. Hugo Bleicher had successfully infiltrated Churchill's network posing as disillusioned Wehrmacht officer 'Colonel Henri.'

Peter Churchill and Odette were taken from Annecy barracks to the Gare de Lyon station in Paris on May 8, 1943, where Hugo Bleicher was waiting and three Gestapo cars took the prisoners to the Fresnes prison, some eleven miles outside Paris. Odette was interrogated and brutally tortured by the Gestapo at their headquarters at 84 Avenue Foch. She was later sentenced to death by the Germans on two counts; The first charge was that she was a British spy and the second because she was a French woman.

Along with six other female SOE agents she was transported to Germany, ironically Odette the only one sentenced to death, was the only one of this group to survive. Miss Andree Borrel, Miss Vera Leigh, Miss Diana Rowden were to die together in Natzweiler Concentration Camp on July 6, 1944. Mrs Yolande Beekman, Miss Madeleine Damerment and Miss Eliane Plewman were executed in Dachau Concentration Camp on September 13, 1944. These SOE agents were taken to Germany as part of the 'Night and Fog' directive to erase all traces of enemies of the Reich, by deporting them to Concentration Camps in Germany.

After many stops and further ill-treatment by the Gestapo, Odette arrived outside Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, in a group of Ukrainian women, on July 18, 1944, and her arrival was described in the book Odette, by Jerrard Tickell:

As the bedraggled cavalcade wound past the end of the lake, the high walls of the camp came into view. A machine-gun post; a grey wall; a black door, twenty feet high. Then silencing the tuneless song of the Ukrainians, another song came to the ears of the women, as a parallel column of female creatures in striped sacking marched briskly past. Their heads were shaven , their eyes were dead and the skin was drawn tightly back from the bones of their faces, so that they were rows of skulls marching. They stepped out in time to the crack of an SS woman's whip, and by order, they sang a merry song, opening and shutting the caverns of their mouths in a macabre melody. The black door of the camp swung open at their approach and on the heels of these scarecrows travesties of womanhood, the new entry shuffled into Ravensbrück. The door swung to and the bolts were shot.

She continued her description of her arrival:

With the Ukrainians she crossed a square and followed the main street of the camp that ran between lines of oblong huts to the washroom, which was to be their quarters for the night. Standing at the doors of their huts, the old inmates, long ago unsexed by privation and by the barber, gibbered at the newcomers and pointed with bony fingers cackling.

An SS woman, plump, confident and scornful, rode a bicycle down the street. She held a long -lashed whip in one hand and a huge dog trotted by her wheels. At her approach, the striped scarecrows scattered, sliding out of sight, cringing away, fearful lest the eye of Dorothea Binz, Chief Wardress and terror of the Camp, should light on them.

There were rows of showers in the washroom, the nozzles set in pipes that ran along the ceiling. Odette turned one tap and a trickle of water spilled on the concrete floor.

Shortly after her arrival Odette was taken to see the Commandant Fritz Suhren who ordered that she should be incarcerated in the camp's Bunker, the camp's prison:

She walked out of the office with the Gestapo man and into the summer sunshine. They crossed a dusty compound and came to a long, low L-shaped building. The Gestapo man stopped. He said, 'This is the prison, the Bunker. Here you will stay. Odette looked upwards at the sky. It was a beautiful day- the sort of day when sun and wind and water and leaf and tree all combine to shout aloud the glory of God. The door of the Bunker was opened by a woman in SS uniform, Margarete Mewes, a peevish, mean little harlot with a bovine face and a receding chin. She and the Gestapo man spoke together and he beckoned to Odette. She took one last look around the blue depths of the sky, as if she was trying to absorb all its clarity and all its life into her very self. Then she stepped into the Bunker.

Odette described what she saw next:

There was a short passage with a barred gate at its end, its spikes touching the floor and the ceiling. On one side of the passage were the cheerful rooms occupied by the SS. The wardress unlocked the gate with the key at her waist and Odette walked through to the inner Bunker. The gate swung to on the spring lock . Before her was a flight of stairs leading downwards. She descended them and walked along an underground passage, white with electric light. The wardress unlocked a door and Odette stepped into a cell whose darkness was opaque. She had to feel her way with her foot and she stretched out her hands before her, like the sightless, so as not to walk into the far wall. The cell door shut with a crash and she heard the sound of retreating steps.

For three months and eleven days, she lived in the darkness, interrupted by brief and blinding visits of her captor.

On April 28, 1945, Odette was taken out of Ravensbrück in a huge Black Maria, and taken to the Neustadt Concentration Camp. Fritz Suhren the former commandant of Ravensbrück, drove Odette to the American forces on May 3, 1945, where he announced, 'This is Frau Churchill. She has been a prisoner. She is a relation to Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of England.' Odette said, in response, 'And this is Fritz Suhren , Commandant of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. Please make him your prisoner.

Fritz Suhren was tried for War Crimes, found guilty and was executed on June 12, 1950.

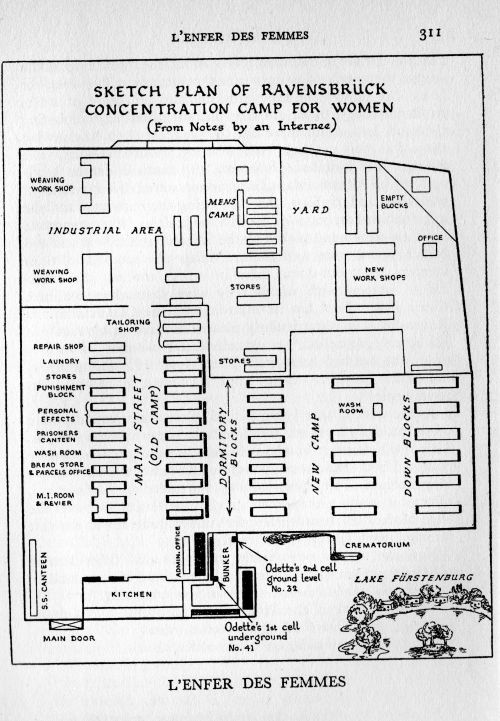

Sketch of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp - Drawn by an inmate

Sources

Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933- 1945, USHMM, Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Sarah Helm, If This Is A Woman: Inside Ravensbruck: Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women, Abacus 2016

Jerrard Tickell, Odette, A New Poertway Book, Chivers Press, Bath, 1984

French L. MacLean, The Camp Men, Schiffer Military History, Atglen, PA, 1999.

Photograph: Bundesarchiv

Drawing, Odette, Chivers Press, Bath

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018