Kutno

German Soldier - Kutno Station

Kutno is located some 31 miles north of Lodz and in December 1939, there were 7,709 Jews residing in Kutno, out of a total population of 27,761. German Army troops reached Kutno on 16 September 1939, and the Germans quickly established a civil administration in the city on 26 October 1939. The Germans carried out arbitrary arrests, plunder of valuables and property, Jews were forced to perform forced labour and all kinds of humiliation and abuse, became the daily norm. The head of the Gestapo in Kutno, Michel Stumpler and his deputy Hoffmann, were especially active in the measures taken against the Jews.

On 3 November 1939, the German authorities established a Jewish Council (Judenrat) in Kutno. Among those on the council were Bernard Holcman –who was the chairman of the council, Moses Fluger, who was deputy chairman, Sender Falc, who was head of the financial department, and other members were Pawel Goldszejder, I. Kubie, Sz. Opoczynski, Lauzer Praszkier, and Maks Zandel. A Jewish police force was established, which was commanded by the Frankenstein brothers and this was subordinated to the Judenrat. The German authorities tasked the Judenrat with registering the Jews, including details of property ownership, in order to facilitate the Germans taking over the businesses. For example, a currency protection squad organised the looting of Jewish property, seizing items such as jewellery, money, and valuable household goods. In December 1939, the Judenrat regularly bribed the German police and civil administration in an effort to appease them. Hoffmann, for example, received furniture for his private residence, valued at approximately 15,000 Reichsmark (RM). On 16 June 1940, the mayor, Wilfried Schurmann, ordered the establishment of a ghetto. The ghetto was located on the property of a former sugar factory named ‘Konstancja’ and included five buildings already occupied by Jews. Some referred to the ghetto as a Jewish camp (Judenlager), as was the case in other cities and towns. The resettlement of the Jews into the ghetto , provided further opportunities for Jewish property and valuables to be plundered. The Jews were ordered to move into the ghetto area within one day. During the transfer, the police forces involved included the local Criminal Police, the Order Police and the SS. The Jews were abused in particular by Josef Schneider and Wilhelm Sauer, who attracted particular attention for their brutality. The Jews were only permitted to bring a small part of their moveable property into the ghetto. Due to limited transportation, most Jews had to carry everything in by hand. The ghetto territory only covered about 5 acres and was isolated from the rest of the city by a brick wall with barbed wire on top. Approximately 7,000 Jews lived in the ghetto initially, including more than 1,000 refugees from many different locations, as well as some Jews who had been resettled into Kutno from the surrounding villages. For example, 150 Jews were brought in from Dabrowicki. Jews were forced to find a home anywhere they could, for example in former inns, horse and cow stalls, and even primitive shelters made of wood and mud. By October 1940, the first cases of typhus were reported. Of the five buildings in the ghetto area, one housed the ghetto guards, and the Judenrat and their families occupied two others. In one of these buildings, little more than a primitive shack, a hospital was set up. It consisted of one room for the physician and four rooms for the patients. On the first floor was the ghetto post office. The local police guarded the ghetto. The ghetto guards received the title of ‘Police Guards, Jewish Camp’. Their headquarters was located on Posen Street. Among others, fifty members of Police Battalion 132 – and after 26 November 1941, thirty-eight members of Police Battalion 41- guarded the Kutno ghetto. They were under the command of Oberleutant Kurt Weissenborn, who was notorious for his corruption. He took large monetary bribes to allow goods to be smuggled into the ghetto. However, the food situation soon became desperate. The Judenrat opened a soup kitchen for the poorest ghetto inmates and succeeded in organising deliveries from farms in Chruscinek in the Gemeinde Strzelce and from a dairy farm in Kutno. Despite these efforts, food supplies remained insufficient. Food was distributed three times a day – breakfast, lunch and dinner – in the Judenrat’s building. The shortages induced a high level of smuggling. There were also occasional deliveries of aid from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC). The corruption of some ghetto guards helped a little, as they permitted some Jews to leave the ghetto to exchange valuables with the non-Jewish population for food. It seems that the Judenrat played a significant role in bribing the guards, but survivor testimonies remain ambiguous regarding the behaviour of the Judenrat. Some survivors accuse members of the Judenrat of granting privileges to themselves and their families, particularly in respect of securing better apartments and larger food rations. The ghetto population referred to the buildings occupied by the Judenrat as the ‘House of Lords.’ During February 1941, some of the ghetto residents organised a riot against the Judenrat. The insurgents demanded that the head of the financial department, Sender Falc, provide a detailed account of all expenditures by the ghetto administration. The protest turned violent, and some of the rioters assaulted Falc. The German police intervened to halt further unrest. As a result of this incident, various smuggling operations involving the ghetto were uncovered, and several people were arrested in May 1941. Among those arrested were a Pole named Zenon Rzymowski and a Jew named Leo Stuczynski from the ghetto. All of the prisoners were sentenced to death and hanged in Wloclawek. After this incident, several members of the Criminal Police and also the ghetto guards were replaced. This resulted in a considerable tightening of the security around the ghetto, which led to the complete isolation of the Jews. The only remaining route to exit and enter the ghetto was a dried-out canal hidden underground, which, however, was soon blocked by the German police.

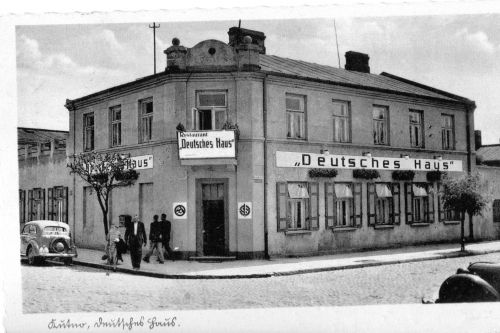

Kutno - Deutsches Haus (Chris Webb Private Archive)

During 1941, an unknown number of Jews from Kutno were deported to forced labour camps in the area around Poznan, or as the Germans renamed it Posen. Here they worked building sections of the highway connecting Posen with Frankfurt an der Oder, a road that led through original German territory (the Altreich). There were several escapes by Jews from the Kutno ghetto to other ghettos such as Ozorkow in the Wartheland and Warsaw in the General Gouvernement . In July 1941, the registered ghetto population in Kutno was 6,015. The health situation in the Kutno ghetto deteriorated, and the death rate from disease and starvation was very high. On 21 March 1942, the head of the civil administration in Inowroclaw sent a letter to the head of the Health Department for the Reichsgau Wartheland, stating that 1,369 persons were infected with typhus and 313 had already died in the Kutno ghetto. The Judenrat managed to bring in two physicians from other ghettos, Juliusz Winsaft and Dr. Aperstein, to provide some medical treatment. Also some Polish physicians tried to help: Jozef Malinowski, Julisz Perkowicz, and B. Jedraszko obtained permission to enter the ghetto to conduct research into epidemic diseases. However, the German authorities did not permit the delivery of typhus serum to the Jews of Kutno. In addition, there were many cases of abscesses and edemas caused by malnutrition, mainly affecting children. In total, more than 660 Jews died of starvation and disease in the Kutno ghetto, comprising about 10 percent of the average ghetto population. These were not the only causes of death, of course; other inhabitants were killed, for example, for leaving the ghetto illegally. The German police taunted the Jews when food deliveries reached the ghetto. They threw the supplies into the crowd that had gathered to provoke a fight and shot at the desperate people grasping for food. The Kutno ghetto became renowned as one of the worst ghettos. In spite of the harsh conditions, the Jews in the Kutno ghetto, particularly the younger element tried to maintain some form of cultural life. They held meetings to discuss literature, sang songs, and organised a library. Attempts were made to establish a school in the ghetto, but the intended building was given to the ghetto hospital, which had a higher priority. Nevertheless, a clandestine education system was established in the ghetto.

German forces started the liquidation of the Kutno ghetto on 19 March 1942. The Underground newspaper of the Warsaw ghetto, ‘Undzer Weg’, reported on 1 May 1942, that the Kutno ghetto had been liquidated on 23 March 1942. A report prepared in April 1942 in the Warsaw ghetto for the Polish government in exile stated that on 26 March 1942, the Jews of the Kutno ghetto were assembled in alphabetical order and loaded onto trucks. The victims were taken from Kutno to the station at Kolo, where they were packed into trucks on a narrow gauge railway, which took them to the deadly gas-vans in the Chelmno death camp. This mass ‘Aktion’ lasted until April 1942, resulting in the death of some 6,000 Jews from the Kutno ghetto. The elderly and the sick who could not be transported to Chelmno were murdered in the Kutno ghetto itself. Following the liquidation ‘Aktion’ the members of the Jewish Police were shot just outside the ghetto area and 30 Jews from the Lodz ghetto were sent to Kutno, as a so-called ‘Aufraumungstrupp’ (clean-up detachment) which was tasked with sorting the possessions of the deported Jews. They too were mistreated and suffered from starvation and diseases, including cases of typhus.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012.

Photographs: Chris Webb Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 13 December 2021