Deblin-Irena

Deblin Festung

Deblin- Irena is located approximately 43 miles northwest of Lublin and in 1927, the population stood at 4,860 included 3,060 Jews. On the first day of the Second World War, 1 September 1939, the town was bombed by German aircraft. There was a Polish military airfield near the town, as were numerous military facilities and a bridge over the Vistula River – and all of these were targets for the Luftwaffe. Because of the area’s strategic importance the heavy bombing continued for a full week. On 8 September 1939, the Polish army retreated from the town and abandoned the nearby airfield as well. There remained only a small garrison to guard the large ammunition dump nearby. On 11 September 1939, the Polish soldiers set fire to the ammunition and military supplies, and they too fled from the region. The heavy bombing caused great damage to the town, entire streets and houses were consumed by fire, and during the first few days of the war, there was a confused flight of the towns inhabitants and many Jews sought refuge in the synagogue from the bombing, whilst other Jews fled the town completely, heading for nearby Pulawy, Ryki and Zelechow, or small villages in the vicinity of Deblin-Irena.

On 20 September 1939, the Germans entered Deblin-Irena, and during the first three weeks of the occupation many residents, Jews and Poles alike, returned to the town, as ordered by the Germans. Shortly after the Germans took control, the Jews were ordered to assemble in the square where the German commander delivered a speech filled with hatred and threats. During those early days the Germans demanded a contribution of 20,000 zloty from the Jewish community, and the Germans took Jews from the streets for forced labour. Most of those taken were assigned to clearing the rubble from the streets and removing the carcasses of animals killed during the bombardments, whilst some Jews were sent to repair the bomb damage at the airfield. In late 1939, the German authorities ordered the Jews to wear armbands and to establish a Jewish Council (Judenrat), consisting of 12 members. The first chairman was Leizer Teichman, a merchant who owned an electrical and household appliance shop, and who was a prominent activist in the Jewish pre-war community. Other members of the Judenrat included Isaac Zelechowsky, who served as treasurer and Moses Kamein and Joseph Kanarivenfogel, who were in charge of organising and drafting manpower for forced labour. He,and subsequent chairmen attempted to soften German demands, mainly by establishing good relations with the local Polish administration. An internal changes in borders resulted in Deblin-Irena to be incorporated on 1 April 1940, into the Distrikt Lublin. That summer the Judenrat sent Jewish conscripts to labour camps in Belzec, Janiszow, and Pawlowice, as well rebuilding the airfield. The Judenrat established its seat in Bankowa Street, next to it was the headquarters of the Jewish Police, whose principal task was to escort the forced labourers each day to and from their places of work. In November 1940, a ghetto was established in Deblin-Irena, in Bankowa, Okolna, Santurska, Wiatraczna, Neidbale, and Pashkudna Streets. The ghetto was not enclosed, there were no fences or gates, but Jews – other than forced labourers who worked on external sites – were forbidden to leave it. Okolna and Santurska Streets bordered on the market square so it was relatively easy for Jews to purchase food from the Polish farmers. A bakery in Okolna Street continued to function and supply the ghetto with bread. Poles who owned a grocery and a food warehouse received authority to continue to employ Jewish workers, both these and the bakery workers were able to smuggle various foods into the ghetto, particularly vegetables. This clandestine activity continued until the ghetto was liquidated, in October 1942.

Soon after the German occupation, at the initiative of a Jewish teacher, Ida Tziterbaum, private school rooms were established for Jewish children, who had been expelled from the schools by order of the Germans. The children studied for two hours a day, in groups of ten or twelve. The study groups continued even after the ghetto was established and approximately 100 children received an education, from eight in the morning until the afternoon. The children studied most of the subjects taught in the general schools in pre-war Deblin-Irena. The children did not study such subjects as Hebrew or Jewish history. In the winter of 1941, a Prisoner of War camp for captured Soviet forces was established in the fortress, known as the Citadel, near the town. The POW’s suffered from famine and brutality, and the conditions of their incarceration was harsh in the extreme. Before long a typhoid epidemic broke out among the POW’s and this spread to the ghetto. The Germans allowed two hospitals to be created in the town, one for the Polish population, which was located in the school building on Sochatsky Street, and one for the Jewish population, within the ghetto itself. The Jewish hospital suffered from constant shortages of medicines, but the Polish doctors arranged for medicines and supplies to be brought from Warsaw and the typhus epidemic in the ghetto subsided during May 1942. During 1941 – 1942, the Germans established five labour camps in Deblin-Irena and its environs – two in the vicinity of the airfield, one on the road to the village of Mierzwiaczka, one near the baggage terminal at the railroad station, and one established during 1942, in the town itself on Lipowa Street. Some 1,000 forced labourers worked at the camps near the airfield, most of them Jews from Deblin-Irena and nearby locations; approximately 300 Polish and Jewish labourers worked in each of the other camps, and in the camp at Lipowa Street approximately 200 forced labourers worked there. In early 1941,Leizer Teichman and Karynfogel, the Jewish Council secretary were banished with their families to Wawolnica, for bribing several Gendarmes to expel an inebriated Kreis official who was searching a Jewish – owned house for textiles. In late spring Kurt Lenk the Landkommissar of Deblin and Ryki, was transferred to Krasnik and Osternak, the Landkommissar in Chelm was moved to Deblin. Kalman Fris appointed chairman of the Judenrat, by Lenk served a few months before arranging with Osternak to resign. He was succeeded in August 1941 by Vevel Shulman. A month later in September 1941, Drayfish, a refugee from Konin, replaced Shulman, as chairman. In March 1941, the ghetto population stood at 3,750 and this number included refugees from Pulawy, the Warthegau and from Deblin-Irena natives that returned from the Warsaw ghetto. A Jewish police force guarded the ghetto from the inside, whilst Gendarmes from the Deblin post, commanded by Franz Philippi were responsible for its external borders. Members of a Sonderdienst unit, subordinated to the Gendarmerie physically guarded the ghetto, initially this was composed of local ethnic Germans and in time they were assisted by Ukrainian auxiliary troops. Polish ‘Blue’ police also assisted in guarding the ghetto. German Gendarmes Rudolf Knapheide, and Johann Peterson and local resident Edward Brok, the Sonderdienst’s Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) commander, were noted for humiliating, beating and killing a number of the ghetto inhabitants. Some of the ghetto inhabitants worked for private German and Austrian firms, including the Schultz, Schwartz and Hochtief construction companies, which oversaw various phases of the Warsaw – to- Lublin railway expansion. Most though, worked either for the Wehrmacht or the Luftwaffe. Women and children grew food for military canteens at the former agricultural school. Women and men unloaded coal from rail cars or cleaned the cars at the Wehrmacht Deblin railway inspectorate. Approximately 200 to 300 Jewish males conscripted by the Wehrmacht reported daily to the citadel. Another 200 to 400 worked at the air base repairing radios, altering airmen’s uniforms, shovelling coal and cutting wood.

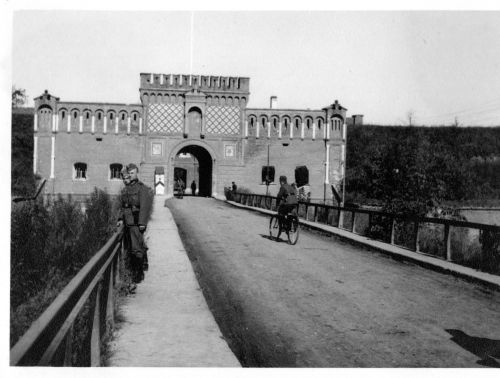

Deblin Fortress -Entrance

Until late 1942, Jewish conscripts at the above work sites earned forced labour wages, whilst those who worked on municipal tasks, such as street cleaning, received no pay at all. In May 1941, approximately 1,000 Jews from the Warsaw, Czestochowa, and Opole ghettos arrived in Deblin to work at various work sites, including the Luftwaffe air base, where 500 to 600 Warsaw Jews and a smaller number of Viennese deportees, who had first been resettled to Opole, levelled the land. When the camp closed in October 1941, the Warsaw Jews were ordered to the Deblin ghetto, and the Jews from Opole, returned to the ghetto there. Those Jews originally deported from Vienna, paid bribes to remain at the camp. In late December 1941, another camp was established on the same site, and 300 Jews were incarcerated there, working to expand the air base’s fuel storage facilities. The Viennese deportees became the camp’s Jewish administrative cadre. Conditions deteriorated in the ghetto from the winter of 1941-42, the German authorities requisitioned winter clothing, for the troops freezing to death on the eastern front, curtailed fuel rations and suspended the use of stoves. The Polish waste collectors were banned from entering the ghetto, latrines overflowed and rubbish piled up in the streets. Unsurprisingly, dysentery and typhus outbreaks followed. Those who fell sick received treatment at an isolation facility and a 30-bed hospital, headed by a refugee from Konin, Dr. Isaar Kawa. As black market trade dwindled, many Jews left the ghetto to find food and fuel. Some 20 women caught outside the ghetto foraging were executed. In April 1942, Drayfish, the chairman of the Judenrat,was among a group of local Jews sent to a penal camp in Kazimierz Dolny, for allegedly registering complaints with the Pulawy Kreishauptmann’s office were shot. Timber merchant Yisrael Weinberg, replaced Drayfish, as chairman of the Judenrat. On 6 May 1942, German-led security forces, under the control of Johann Peterson, arrived and ordered the Jews to assemble by 9.00 a.m. at the market square. Jews still residing in several nearby villages, such as Bobrowniki, also gathered there. The Jews were surrounded by armed Germans and Ukrainian auxiliaries and SS men, and they waited hours. At 2.00 p.m. approximately 1,000 conscripts and labour camp inmates were marched from their work sites to the square and ordered to form a separate line. Local employers’ representatives selected between 200 -500 people to remain behind. The line of inhabitants slated for ‘resettlement’ became composed overwhelmingly of the sick, the elderly, mothers with infants and children and those left homeless by a recent fire. Approximately 50 people were killed, mainly for trying to join the forced workers line. At about 6.00 p.m. the Ukrainian auxiliaries marched some 2,500 Jews, were led via Warshavska Street to the railroad station. Among the deportees were Vevel Shulman, the former chairman of the Judenrat, and he along with the other deportees were loaded onto freight cars that took them to the Sobibor death camp, where death in the gas chambers awaited them. After the deportation ‘Aktion’ had been concluded the Jews who had remained were sent back to their homes, and a new Judenrat created, under Israel Weinberg. Their first task was to gather up the corpses of those Jews murdered during the deportation ‘Aktion.’ The corpses were cleared from the streets and taken to the synagogue and then were taken to the Jewish cemetery in nearby Bobrowniki

On 13-14 May 1942, some 2,042 deportees from Presov, Slovakia were resettled into the Deblin-Irena ghetto. In August 1942, the Jewish Social Self-Help (JSS) noted some 5,800 Jews residing in Deblin-Irena; 1,800 native and 4,000 non-native Jews. Many of the Jews had been designated for work in Deblin-Irena, 200 Jews came from Ryki, 300 came from Gniewoszow, and Zwolen, and a similar sized group from Stezyca. Others were fugitives from deportations in Baranow nad Wieprzem, and later on Adamow. Because local Jews were convinced only the employed would escape ‘resettlement’ they tried to fill the best available jobs, leaving 200 Jews from Presov as unpaid municipal conscripts. Approximately 180, to 200 Slovak Jews were included in a quota of workers for the Schultz firm. Some skilled Slovak Jews found work at the Luftwaffe construction site camp, where Jews from Deblin-Irena, Warsaw and Vienna also worked. Many of the Slovak Jews were unaccustomed to the ghetto’s poor sanitation contracted typhus and perished.

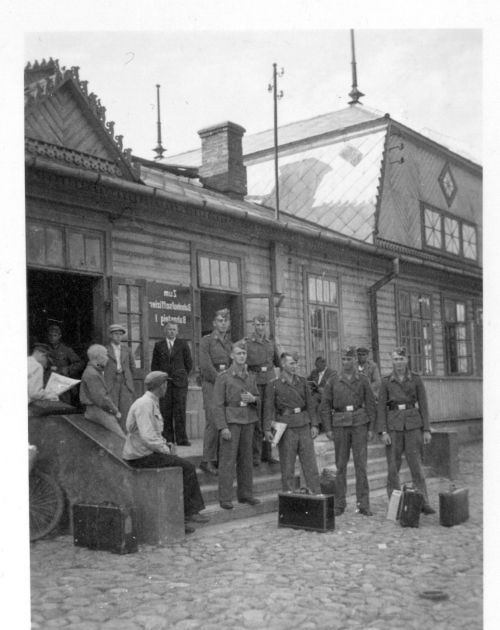

Deblin Bahnhof - ( Chris Webb Private Archive)

On 15 October 1942, members of the German Gendarmerie, SS troops and Ukrainian auxiliaries all under the command of SS- Obersturmführer Grossman, commander of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) in Pulawy, arrived to carry out the final liquidation of the Deblin-Irena ghetto. Hundreds of Jews, mostly the Presov deportees were still unpacking their belongings were murdered by the Germans and Ukrainian forces during the house-to-house searches. Approximately 2,500 Jews, mainly from Slovakia were sent to the Treblinka death camp. Approximately 2,700 Jewish labourers were retained, whilst another 100 people, mostly Judenrat members, Jewish Police members and their families were assigned to sort and ship the deportee’s belongings from the ghetto. Many Jews tried to avoid the deportation ‘Aktion ‘ attempting to enter the Luftwaffe camp, although some were shot at the camp’s gates, about 500 people, including approximately 100 children managed to enter the camp, usually in exchange for bribes. More than 1,000 workers were in the camp, they were assigned to work on construction projects, paving airplane runways, and to the sawmill that operated in the camp, and to various service tasks. Living conditions were not as harsh as in other labour camps. By the end of 1943, however, living conditions in the labour camp deteriorated, rations were reduced, and some forced labourers were executed after being accused of indolence or acts of sabotage. In charge of the Jewish labourers at the camp was a man called Vishinsky, a Volksdeutsche, from Silesia. The Jewish camp elder was Hermann Wenkrat, who originated from Germany, and he was able to arrange with the camp authorities, the exemption of several Jewish women from working, so that they might care for the children in the camp, many of whom were ill. The women managed to organise the children into study groups, and the children studied Jewish history and celebrated Jewish holidays. In September 1943, the labour camp near the train station was liquidated and the Jews incarcerated, were transferred to the Jewish labour camp at Poniatowa, also within the Lublin region. The labour camp at the airfield continued to operate until 22 July 1944, until the approaching Red Army made the Germans evacuate the camp. The workers were transferred to a labour camp near Czestochowa, which belonged to the Hugo Schneider AG (HASAG) industrial concern. They were sent in two transports, the men went first, whilst the second transport included women and children. Some of the children, who were too sick to travel or were very young, were taken to the Jewish cemetery in Deblin-Irena where they were murdered.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

Yizkor Book Project, Deblin – Irena Ghetto, JewishGen Inc 2009

Photographs:Chris Webb Private Archives

© Holocaust Historical Society 2019